Academia.edu no longer supports Internet Explorer.

To browse Academia.edu and the wider internet faster and more securely, please take a few seconds to upgrade your browser .

Enter the email address you signed up with and we'll email you a reset link.

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

Critical thinking, negative academic emotions, and achievement: A mediational analysis

The study tested the control-value theory's (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun, Goetz, Titz, & Perry, 2002) assumptions regarding the cognitive-motivational effects of emotions on achievement. Specifically, the link between critical thinking and achievement was examined among 220 engineering students. The Academic Emotions Questionnaire (Pekrun, Goetz, & Frenzel, 2005) was used to assess how specific negative academic emotions mediated the effect of critical thinking on achievement. Results showed that critical thinking was positively associated with achievement, but negative emotions (anger, anxiety, shame, boredom, and hopelessness) were negatively correlated with achievement. Anxiety and hopelessness were found to completely mediate the relationship between critical thinking and academic achievement. The results suggested that when students engage in critical thinking, their cognitive resources are used appropriately for the task to be completed, making them less anxious and less hopeless, thereby increasing their achievement.

Related Papers

American Journal of Engineering Education (AJEE)

Patricia Ralston

Research in Higher Education

Robert Stupnisky

kang fong luan , International Journal of Education & Literacy Studies [IJELS]

Good critical thinkers possess a core set of cognitive thinking skills, and a disposition towards critical thinking. They are able to think critically to solve complex, real-world problems effectively. Although personal emotion is important in critical thinking, it is often a neglected issue. The emotional intelligence in this study concerns our sensitivity to and artful handling of our own and others’ emotions. Engaging students emotionally is the key to strengthening their dispositions toward critical thinking. Hence, a study involving 338 male and female graduate students from a public university was carried out. They rated the Emotional Intelligence Scale and Critical Thinking Disposition Scale. Findings suggested that emotional intelligence and critical thinking disposition were positively correlated (r=.609). Differences in terms of age, gender, and course of study also formed part of the analysis.

2011 ASEE Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings

James Lewis

International Journal for the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning

Rich Lewine

2006 Annual Conference & Exposition Proceedings

clifton martin

Rosemary Ogochukwu Igbo

Educational Psychology Review

Reinhard Pekrun

Universal Journal of Educational Research

Eddiebal Layco

RELATED PAPERS

Ingenierías

Miguel Angel

Croatica et Slavica Iadertina

Zdenka Matek Šmit

Roger Pullin

Proceedings of the International Astronomical Union

Maurizio M. Busso

Current Topic in Lactic Acid Bacteria and Probiotics

Chul-Sung Huh

Radiation Research

Annals of Agricultural Sciences

Mohammed Abou-Elseoud

The Scientific World Journal

Mohd Faizul Mohd Sabri

Quaestiones Geographicae

Anton Michálek

Journal of Korean Academy of Nursing Administration

Hyunyoung Park

BMC Geriatrics

MATEC Web of Conferences

Zofia Szweda

Biology of the Cell

André Mazabraud

Psychology of Women Quarterly

Jennifer Livingston

Nutrition Journal

Mark Messina

Katarzyna A Jadwiszczak

Memorias del VI Encuentro Provincial de Educación Matemática

Margot Rodriguez

Jurnal Pengabdian Masyarakat: Darma Bakti Teuku Umar

Putri Maulina

Annals of Pediatric Cardiology

Tarique Hussain

Journal of Physics: Conference Series

D. R . Napoli

Journal of Nepal Medical Association

ROSHAN KHATRI

Teti Sobari

BMJ Open Ophthalmology

Hans Thulesius

European Heart Journal

Ronen Durst

amnah ismail

- We're Hiring!

- Help Center

- Find new research papers in:

- Health Sciences

- Earth Sciences

- Cognitive Science

- Mathematics

- Computer Science

- Academia ©2024

- < Previous

Home > FACULTY_WORKS > FACULTY_RESEARCH > 1277

Faculty Research Work

Critical thinking, negative academic emotions, and achievement: a mediational analysis.

Felicidad T. Villavicencio , De La Salle University-Manila

College of Liberal Arts

Department/Unit

Document type, source title.

Asia-Pacific Education Researcher

Publication Date

The study tested the control-value theory's (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun, Goetz, Titz, & Perry, 2002) assumptions regarding the cognitive-motivational effects of emotions on achievement. Specifically, the link between critical thinking and achievement was examined among 220 engineering students. The Academic Emotions Questionnaire (Pekrun, Goetz, & Frenzel, 2005) was used to assess how specific negative academic emotions mediated the effect of critical thinking on achievement. Results showed that critical thinking was positively associated with achievement, but negative emotions (anger, anxiety, shame, boredom, and hopelessness) were negatively correlated with achievement. Anxiety and hopelessness were found to completely mediate the relationship between critical thinking and academic achievement. The results suggested that when students engage in critical thinking, their cognitive resources are used appropriately for the task to be completed, making them less anxious and less hopeless, thereby increasing their achievement. © 2011 De La Salle University, Philippines.

Recommended Citation

Villavicencio, F. (2011). Critical thinking, negative academic emotions, and achievement: A mediational analysis. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher , 20 (1), 118-126. Retrieved from https://animorepository.dlsu.edu.ph/faculty_research/1277

This document is currently not available here.

Since October 23, 2020

Advanced Search

- Notify me via email or RSS

- Collections

- Disciplines

- Colleges and Units

- Submission Consent Form

- Animo Repository Policies

- Animo Repository Guide

- AnimoSearch

- DLSU Libraries

- DLSU Website

Home | About | FAQ | My Account | Accessibility Statement

Privacy Copyright

Philippine E-Journals

Home ⇛ the asia-pacific education researcher ⇛ vol. 20 no. 1 (2011), critical thinking, negative academic emotions, and achievement: a mediational analysis.

Felicidad T. Villavicencio

Discipline: Education

The study tested the control-value theory’s (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun, Goetz, Titz, & Perry, 2002) assumptions regarding the cognitive-motivational effects of emotions on achievement. Specifically, the link between critical thinking and achievement was examined among 220 engineering students. The Academic Emotions Questionnaire (Pekrun, Goetz, & Frenzel, 2005) was used to assess how specific negative academic emotions mediated the effect of critical thinking on achievement. Results showed that critical thinking was positively associated with achievement, but negative emotions (anger, anxiety, shame, boredom, and hopelessness) were negatively correlated with achievement. Anxiety and hopelessness were found to completely mediate the relationship between critical thinking and academic achievement. The results suggested that when students engage in critical thinking, their cognitive resources are used appropriately for the task to be completed, making them less anxious and less hopeless, thereby increasing their achievement.

exercise. Results suggested that student misconceptions about the technologies often undermine most of the learning benefits afforded by them. For teachers, this meant that some significant orientation at the beginning of courses needs to occur to reveal to the students what the learning technologies are for, and how students can benefit from a reflective and more strategic approach to their use.

Share Article:

ISSN 2243-7908 (Online)

ISSN 0119-5646 (Print)

- Citation Generator

- ">Indexing metadata

- Print version

Copyright © 2024 KITE E-Learning Solutions | Exclusively distributed by CE-Logic | Terms and Conditions

Pathways from cognitive flexibility to academic achievement: mediating roles of critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety

- Open access

- Published: 20 January 2024

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article

- Semirhan Gökçe ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-4752-5598 1 &

- Pınar Güner ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0003-1165-0925 2

849 Accesses

Explore all metrics

The purpose of this study is to examine the mediating roles of critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement. A cross-sectional study was held to observe and compare path coefficients among latent and observed variables across 662 university students studying elementary mathematics education. In concur with grade point average scores, Cognitive Flexibility Scale, UF/EMI Critical Thinking Disposition Instrument and Math Anxiety-Apprehension Survey scores were utilized for structural equation modeling analyses. The results of this study indicated that freshman students experience the greatest impact from cognitive flexibility on academic achievement, while sophomores experience the least impact. Additionally, with the exception of the model for sophomore students, the mediating effects of the critical thinking disposition between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were positive and statistically significant. Additionally, none of the models’ estimations of how mathematics anxiety would mediate between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were statistically significant. Last but not least, for junior students only positive and statistically significant mediating effects of critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were found. This study put forth evidence to investigate cognitive flexibility, critical thinking disposition and math anxiety in higher education and to show the total, direct and mediating effects on academic achievement.

Similar content being viewed by others

Motivational and Math Anxiety Perspective for Mathematical Learning and Learning Difficulties

Math-Failure Associations, Attentional Biases, and Avoidance Bias: The Relationship with Math Anxiety and Behaviour in Adolescents

Eva A. Schmitz, Brenda R. J. Jansen, … Elske Salemink

Investigating factors affecting student academic achievement in mathematics and science: cognitive style, self-regulated learning and working memory

Tzu-Hua Wang & Chien-Hui Kao

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The factors affecting achievement are one of the subjects that have garnered the attention in educational research. Recent studies investigating the prominent concepts linked to academic achievement highlight cognitive flexibility, critical thinking and mathematics anxiety. It is inevitable that these variables would play important roles in both shaping mathematics instruction and teacher education as well. For instance, critical thinking is a skill about understanding the meaning of various situations and making appropriate decisions consequently (Serin et al., 2018 ). Hence, critical thinking disposition could be defined as the “person’s consistent internal motivations to act toward, or respond to, persons, events, or circumstances in habitual, yet potentially malleable ways” (Facione et al., 2000 ). There are many acquisitions related to critical thinking and critical thinking dispositions in curricula from primary school to university level that points to the importance of teachers to provide students with these skills. The related literature states that there is a positive relationship between critical thinking skills and academic achievement (Abrami et al., 2008 ). Teachers and pre-service teachers need to have a critical thinking disposition so that they can reflect on their students. Critical thinking disposition is an approach that teachers and students should have. In order for students to gain critical thinking skills, they should have tendencies to use skills such as analyzing, understanding the reasons for events, recognizing relationships, interpreting and evaluating events. However, these tendencies do not develop spontaneously and automatically. Besides, philosophical and psychological approaches, which view critical thinking as a goal to be accomplished via education, concentrate more on how to develop critical thinking and how to overcome obstacles than on the cognitive foundations of this skill (Scheibling-Sève et al., 2022 ). It is quite unlikely to fully understand critical thinking without being aware of these fundamental mechanisms, though, as critical thinking depends on several cognitive processes. In particular, focusing on cognitive approaches makes it feasible to comprehend how reasoning processes are resisted and how biases influence decisions and thus making it possible to take into account the barriers to the critical thinking disposition (Scheibling-Sève et al., 2022 ). It points the need of focusing on interaction between critical thinking disposition and cognitive flexibility.

In addition to critical thinking disposition, it is important for students to gain cognitive flexibility in order for the curriculum to achieve its purpose. Cognitive flexibility is the ability to choose and use the appropriate strategy as one’s tasks or goals change and defined as “flexible reassembly of preexisting knowledge to adaptively fit the needs of a new situation” (Spiro et al., 1992 , p. 59). According to Stad et al. ( 2018 ), since classroom activities are based on cognitive flexibility, poor cognitive flexibility skills might cause students to fail in simple tasks and in their progressive learning. Therefore, teacher intervention is important to support cognitive flexibility. The students’ cognitive flexibility levels could be used to predict their future mathematics achievement (Stad et al., 2018 ). Cognitive flexibility has been found to be particularly relevant to mathematics achievement, as mathematics subjects require switching between different aspects of given tasks or solution strategies. Many studies have explored the possible effects of motivating factors, prior knowledge, and instructional interventions on cognitive flexibility. However, although emotions are one of the most significant factors have a significant impact on academic achievement, learning environments, instruction and students’ motivation and cognition, the role of emotions in the development of flexibility has received little attention (Jiang et al., 2021 ). Mathematics anxiety is thought to be one of the many emotions that affect cognitive flexibility and mathematics learning (Ashcraft, 2002 ). In order to comprehend how mathematics anxiety might influence cognitive flexibility and eventually academic achievement, the current study examined the association between mathematics anxiety and cognitive flexibility as well as the potential structure underlying this relationship.

- Critical thinking disposition

Critical thinking has two different dimensions: critical thinking skills and critical thinking dispositions. Rudd ( 2007 ) defines critical thinking skills as the ability to use the logical thinking approach needed to understand concepts, make decisions, and solve problems. On the other hand, critical thinking disposition is a desire to use critical thinking skills (Zhang, 2003 ). Critical thinking disposition enables to predict critical thinking skills. Teacher educators first need to determine their critical thinking dispositions in order to develop their critical thinking skills. Critical thinking disposition is the motivation to solve problems and understand events, to make decisions using the necessary information and to evaluate them (Facione et al., 1998 ). Studies examining pre-service teachers’ critical thinking dispositions in the literature revealed that learning experiences in training programs affect critical thinking skills and tendencies (Abrami et al., 2008 ). In order to develop these skills, teacher training programs should provide appropriate learning experiences and teaching environments. Critical thinking skills and critical thinking dispositions are related concepts and the development of critical thinking skills in students is possible with the reflection of necessary features, activities and approaches to the education and training process through teachers. Although there are studies that reveal the relationship between critical thinking skills and academic achievement, results on the relationships between achievement and other variables are limited (Abrami et al., 2008 ). In this direction, it is thought that it is important to determine the level of disposition required for critical thinking in pre-service mathematics teachers and to determine the variables that are related to it in order to make the necessary interventions.

- Cognitive flexibility

Cognitive flexibility is the capacity to switch between goals or tasks that stimulate thoughts which includes being flexible in adapting to changing goals or stimuli (Rueda et al., 2005 ). Cognitive flexibility begins to develop in the preschool period, becomes highly developed around the age of 10 (Blaye et al., 2006 ) and continues to develop throughout adulthood (Anderson, 2002 ). It is stated that cognitive flexibility plays an important role in academic success and learning by making it easier for students to change their perspectives and adapt to new situations (Magalhães et al., 2020 ). While there is growing evidence that there are important associations between cognitive flexibility and executive function, the nature of these associations remains poorly specified (Blakey et al., 2016 ). Therefore, cognitive flexibility would be discussed in the context of its’ common definition (i.e. the ability to adjust our thoughts and flexible behaviors in response to changes in our goals or the environment).

At this point, the scarcity of studies in the literature that consider cognitive flexibility as a predictor of academic success draws attention. Some studies show cognitive flexibility with counting and computation skills in mathematics and mathematics skills that required more conceptual or abstract knowledge (Purpura et al., 2017 ), while others with literacy (McClelland et al., 2014 ). Some studies have concluded that students with low mathematics achievement have difficulty in flexibly switching between solution strategies (McLean & Hitch, 1999 ). Magalhães et al. ( 2020 ) concluded that cognitive flexibility is an important determinant for school success, especially in older students. Although the limited prior studies indicate a relationship between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement (McLean & Hitch, 1999 ), the findings on the role of cognitive flexibility on academic achievement differ. This situation reveals that more studies are needed as it creates difficulties in interpreting the relationship between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement. Since cognitive flexibility enables students to learn from their mistakes and feedback, use alternative strategies, and construct knowledge simultaneously (Anderson, 2002 ; Ionescu, 2012 ), the use of this skill in the classroom is of great importance (Magalhães et al., 2020 ). Consequently, it is important to investigate the development of this skill, especially in pre-service teachers who would shape the mathematics teaching in the coming years.

Math anxiety

Mathematics anxiety corresponds to fear and negative feelings towards mathematics. The relationship between mathematics anxiety and achievement is highly effective on learning mathematics. It is stated that high mathematics anxiety leads to alienation from mathematics and negative attitude (Ashcraft, 2002 ). Teachers’ attitudes, teaching environment, and teaching methods could be effective in reducing or increasing students’ math anxiety (Eden et al., 2013 ). According to Maloney and Beilock ( 2012 ), the negative effect of mathematics anxiety on mathematics learning may be greater than the deficiencies in mathematics curriculum or teacher education programs. It is emphasized by National Council of Teachers of Mathematics (NCTM) that teachers with high mathematics anxiety cannot enjoy mathematics teaching and therefore cannot be successful in mathematics teaching (Gresham, 2018 ). It is an issue that needs to be highlighted, as teachers with this feeling may unintentionally convey their math anxiety to their students (Boyd et al., 2014 ). Mathematics anxiety might lead students to prefer teaching at earlier grade levels or in branches that do not include mathematics. Pre-service teachers with mathematics anxiety are likely to have negative attitudes towards mathematics and mathematics lessons, show poor performance in mathematics teaching, use standard mathematical rules and algorithms rather than conceptual understanding and student-centered teaching, and teach in which they are active (Brady & Bowd, 2005 ). Since many teachers and pre-service teachers tend to avoid mathematics due to their lack of confidence, skills and mathematical knowledge, the emphasis on working on mathematics anxiety has increased again recently (Lake & Kelly, 2014 ). Teacher education programs are effective in increasing the quality of mathematics teaching and reducing mathematics anxiety. Defining, identifying and reducing mathematics anxiety in pre-service teachers is important in terms of developing mathematical learning (Gresham, 2018 ) and improving teacher education programs.

In the literature, some studies investigate the relationship between cognitive flexibility and critical thinking disposition (e.g. Scheibling-Sève et al., 2022 ), critical thinking disposition and academic achievement (e.g. Abrami et al., 2008 ), cognitive flexibility and mathematics anxiety (e.g. Ashcraft, 2002 ), cognitive flexibility and academic achievement (e.g. Magalhães et al., 2020 ; McLean & Hitch, 1999 ). However, the research works concerning the inter-variable relationships and mediating effects by considering these variables altogether is very limited. Moreover, age is an important factor for cognitive flexibility (Anderson, 2002 ) and critical thinking disposition (Dunn et al., 2014 ). According to several studies, there is a significant difference in critical thinking disposition of university students based on grade level (Kawashima & Shiomi, 2007 ). Furthermore, pre-service mathematics teachers’ mathematics anxieties could be related to their previous experiences with mathematics as students, the influence of their teachers, or teacher training programs (Raymond, 1997 ). Some studies have found that grade level is a strong predictor of mathematics anxiety (Birgin et al., 2010 ; Ma, 1999 ).

To sum up, there exist studies examining cognitive flexibility, critical thinking disposition, and mathematics anxiety separately with mathematics performance or the relations between these variables. It is also stated in the literature that cognitive flexibility is an important concept for the execution of mathematical skills, especially counting and calculation skills (Purpura et al., 2017 ). In addition, it is known that critical thinking disposition provides motivation in problem solving, understanding mathematics and making mathematical decisions (Facione et al., 1998 ; Rudd, 2007 ). Mathematics anxiety appears to be a mediator variable in some studies investigating the relationships between cognitive and affective variables (Güner & Gökçe, 2021 ; Geary et al., 2023 ; Maldonado Moscoso et al., 2020 ; Zhang & Wang, 2020 ). On one hand, cognitive flexibility is one of the essential component of professional development and mathematical expertise (Baroody, 2003 ; Star & Newton, 2009 ). On the other hand, critical thinking is a high-order skill that encompasses cognitive processes such as problem-solving, logical reasoning, and decision-making (Rudd, 2007 ). According to Ennis ( 1985 ), individuals whom exhibit a critical thinking disposition make an effort to learn more about the setting or problem, to challenge the explanations, and to come up with alternative solutions. Studies also have shown that the tendency to think critically increases the responsibility to continue thinking, thus enabling awareness of thoughts, and thus has an effect on anxiety (Sugiura, 2013 ).

The purpose of this study is to examine the mediating roles of critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement of preservice mathematics teachers. In general, the courses in Turkish mathematics teacher education programs consist of three groups: (1) teaching profession courses, (2) mathematics courses and (3) general culture courses. In the first year, general culture courses are common. However, mathematics courses are dominating in the second year. In the third grade, mathematics teaching courses prevail, while teaching practices come to the fore in the fourth grade. Grade-based comparison of these changes and the variables addressed in this study is important in terms of evaluating the impact of the courses in teacher education program on the professional development of pre-service teachers. For this reason, we think that it is necessary to explore differences in mediating mechanisms at different grades of mathematics teacher education programs.

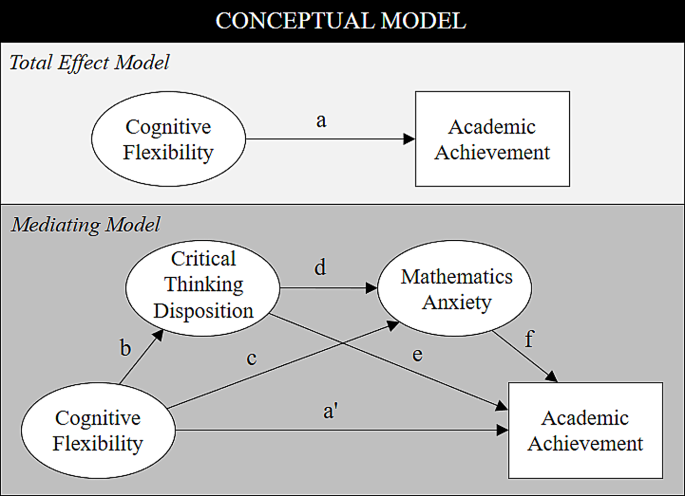

In our conceptual model, it is predicted that both critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety could be appropriate mediators. The current study is noteworthy both for determining the levels of pre-service teachers for these variables and for understanding the relationships between the concepts across grade levels as shown in Fig. 1 .

The conceptual model

This study was designed to test the following research hypotheses based on the conceptual model.

H1 . Cognitive flexibility has a direct effect on academic achievement.

H2 . Cognitive flexibility has a direct effect on critical thinking disposition.

H3 . Cognitive flexibility has a direct effect on mathematics anxiety.

H4 . Critical thinking disposition has a direct effect on mathematics anxiety.

H5 . Critical thinking disposition has a direct effect on academic achievement.

H6 . Mathematics anxiety has a direct effect on academic achievement.

H7 . Critical thinking disposition mediates the relationship between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement.

H8 . Mathematics anxiety mediates the relationship between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement.

H9 . Critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety mediate the relationship between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement.

A cross-sectional study was held to observe and compare path coefficients among critical thinking disposition, cognitive flexibility, mathematics anxiety and academic achievement across freshman, sophomore, junior and senior students.

Participants

The participants were 662 university students (129 freshman, 152 sophomore, 252 junior and 129 senior) studying four year elementary mathematics education program. The gender distribution of the preservice teachers is 544 females and 118 males. The ages of the participants ranged between 18 and 22.

The following three measures were utilized to collect data: (1) Cognitive Flexibility Scale (CFS), (2) UF/EMI Critical Thinking Disposition Instrument (University of Florida Engagement, Maturity, and Innovativeness) and (3) Math Anxiety-Apprehension Survey (MASS). The first measure of the study is the Cognitive Flexibility Scale. This scale aims to measure behavioral flexibility as well as the adaptation and tolerance to ambiguity with 12 items having 6-point Likert type. We used Turkish version of this scale adapted by Çelikkaleli ( 2014 ) in which high score denotes high level of cognitive flexibility. The second measure of the study is the UF/EMI Critical Thinking Disposition Instrument. Besides, this scale has 25-items with 5-point Likert type and focused on engagement (looking for opportunities to use skills and abilities to reason, to solve problem, and to make judgments), cognitive maturity (being aware of tendencies and prejudices in decision-making process) and innovativeness (having intellectual curiosity and seeking to learn new information by researching, reading and questioning). UF/EMI Critical Thinking Disposition Instrument was adapted into Turkish by Ertaş-Kılıç and Şen ( 2014 ) and high score indicates high level of critical thinking disposition. The third measure of the study is the Mathematics Anxiety-Apprehension Survey (MAAS), developed by Ikegulu ( 1998 ). This 5-point Likert type survey consisting of 20 items was used to measure the instructional and/or classroom mathematics anxiety. The higher scores represent the existence of high math anxiety.

We carried out validity and reliability analyzes of the measures. In this context, Cronbach’s alpha coefficients (measure of internal consistency) were calculated and confirmatory factor analyzes were performed by using the lavaan package of the R program (Rosseel, 2012 ). The reliability values obtained as a result of the analyzes performed on the obtained data were high. For cognitive flexibility scale, these values were 0.786, 0.812, 0.755, 0.839, respectively. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of critical thinking disposition instrument were 0.875 for freshman, 0.858 for sophomore, 0.865 for junior and 0.887 for senior students. Finally, the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of math anxiety apprehension survey were found as 0.898, 0.862, 0.895 and 0.895 for freshman, sophomore, junior and senior students, respectively. Confirmatory factor analysis findings are used to evaluate the validity of the measures (Sireci et al., 2008 ). In the analyzes performed, it was observed that the χ 2 /df, SRMR, RMSEA, CLI and TLI values showed that the data fit the model based on the values specified in Table 1 for all grade levels.

In undergraduate level, pre-service mathematics teachers took mathematics field courses (such as analysis, abstract algebra, linear algebra, analytical geometry, statistics, and probability) as well as mathematics teaching courses (such as history of mathematics, teaching numbers, teaching geometry and measurement, teaching probability and statistics, teaching algebra, mathematical connections and problem solving). Hence, cumulative grade point averages (CGPA) were taken into account within the scope of academic achievement of pre-service teachers.

Data analysis

The structural equation modeling (SEM) analyses were carried out as part of the study utilizing the lavaan package of R. The structural relationships between the critical thinking disposition, cognitive flexibility, math anxiety and academic achievement variables in the proposed models were examined independently for each grade in the suggested models. Table 1 employs the acceptable and good fit indices of the models.

The results would be shared under two headings as comparative and SEM analysis.

Comparative analysis

A one-way between subjects ANOVA was used to determine whether critical thinking disposition, cognitive flexibility and math anxiety differ according to the grade levels of university students. In this context, we checked the assumptions of ANOVA. The statistics for normality assumption is given in Table 2 .

The skewness and kurtosis values between − 1.50 and + 1.50 are viewed as indicating a normal distribution. Moreover, Levene test was employed to determine the homogeneity of variances and non-significant p values showed that the variances of each group were about the same. The descriptive statistics of measures for overall and for each grade level separately are given in Table 3 .

The correlation coefficients in Table 3 showed that cognitive flexibility has a significant and positive relationship with critical thinking disposition ( r = .631, p < .01), has a significant and positive relationship with academic achievement ( r = .312, p < .01) and has a significant and negative relationship with mathematics anxiety ( r =-.488, p < .01). Moreover, critical thinking disposition has a significant and positive relationship with academic achievement ( r = .323, p < .01) and has a significant and negative relationship with mathematics anxiety ( r =-.563, p < .01). Finally, mathematics anxiety has a significant and negative relationship with academic achievement ( r =-.366, p < .01). For each grade level, the correlation coefficients among variables from each grade are consistent with the overall participants’ statistics. From Table 3 , it was also observed that the mean scores of cognitive flexibility, critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety across grade levels were close to each other. A one-way between subjects ANOVA was conducted to compare these mean scores across freshman, sophomore, junior and senior students. It was found that there were not a significant effect of grade level on critical thinking disposition [F(3, 658) = 1.394, p = .243], cognitive flexibility [F(3, 658) = 1.373, p = .250] and mathematics anxiety [F(3, 658) = 1.050, p = .370] at p < .05 level.

SEM analysis

For the measures used in the study, the confirmatory factor analyses (CFA) were conducted across grade levels and the obtained indices are presented in Table 4 .

In Table 4 , the results of CFA showed that the χ 2 /df, RMSEA, CFI, TLI, and SRMR indices have either good or acceptable fit. Afterwards, the structural equation modeling was utilized to test the hypothesized theoretical relationships in the provided conceptual model (see Fig. 1 ). As indicated in Table 5 , the fit indices of models in each grade level show how well the data supported hypothesized relationships.

For each grade, the total effect and mediating models are tested whether to have acceptable or good fit indices in terms of χ 2 /df, SRMR, RMSEA, CFI and TLI. In mediating models, critical thinking disposition and math anxiety are the mediators. We tested mediating models to derive the direct, indirect and total effects of cognitive flexibility on academic performance through critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety for freshman, sophomore, junior and senior students. Hypotheses, paths, standardized regression weights, significance values and decisions of each model could be found in Table 6 .

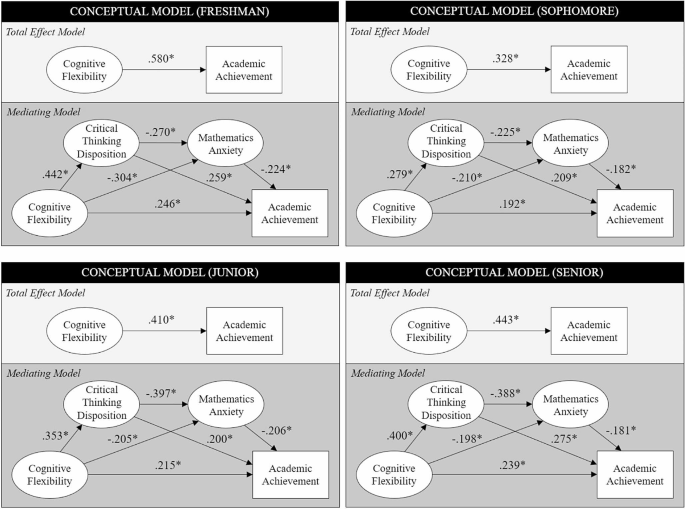

In completely standardized solutions (std. all), both latent and observed variables are standardized. Based on Std. all values in Table 6 , both cognitive flexibility and critical thinking disposition demonstrated a direct, positive, and statistically significant effect on academic achievement in all models (H1 and H3, p < .05). On the other hand, mathematics anxiety had a direct, negative and statistically significant effect on academic achievement in all models (H5, p < .05). When the effect of cognitive flexibility on critical thinking disposition was concerned, a direct, positive, and statistically significant effect was found in all models (H2, p < .05). Moreover, cognitive flexibility and critical thinking disposition showed a direct, negative, and statistically significant effect on mathematics anxiety in all models (H4 and H6, p < .05). When we focused on indirect effects, we observed that the mediating effects of critical thinking disposition between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were positive and statistically significant except the model for sophomore students (H7, p < .05 for freshman, junior and senior but p ≥ .05 for sophomore). Besides, the mediating effects of mathematics anxiety between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were not statistically significant for all models (H8, p ≥ .05). Finally, the mediating effects of critical thinking disposition together with mathematics anxiety between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were positive and statistically significant only within the model for junior students (H9, p < .05 for junior but p ≥ .05 for others). Path coefficients of the models for freshman, sophomore, junior and senior students are shown in Fig. 2 .

Path coefficients of total effect and mediation analysis

In total effect models, there was a decrease in the effect of cognitive flexibility on academic achievement from freshman to sophomore while there was an increasing trend after sophomore (0.580* → 0.328* → 0.410* → 0.443*). In mediating models, there was a similar tendency between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement (0.246* → 0.192* → 0.215* → 0.239*). On the other hand, the critical thinking disposition had decreasing effects on academic achievement from freshman to junior but increasing effect from junior to senior (0.259* → 0.209* → 0.200* → 0.308*). Moreover, the effect of mathematics anxiety on academic achievement differed from cognitive flexibility and critical thinking disposition. In other words, while the negative effect of mathematics anxiety on academic achievement decreased from freshman to sophomore, increased from sophomore to junior and then decreased from junior to senior (− 0.224* → − 0.182* → − 0.206* → − 0.181*).

There were three indirect effects (IEs) from cognitive flexibility to academic achievement. In IE 1 , the mediator was the critical thinking disposition. In IE 2 , the mediator was the mathematics anxiety. Finally, both the critical thinking disposition and the mathematics anxiety were the mediators in IE 3 . The further analysis was conducted to determine the degree of the mediating effect in conceptual models. Accordingly, a ratio of 0.80 and above indicates that it is a full mediating effect, a ratio between 0.20 and 0.80 indicates that there is a partial mediating effect, and that a ratio below 0.20 does not create a mediating effect (Hair et al., 2014). For freshman, IE 1 was statistically significant and positive but IE 2 and IE 3 were not statistically significant. We obtained the ratio as 0.25 and found that critical thinking disposition had partial mediating effect between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement. For sophomore, none of the indirect effects (IE 1 , IE 2 and IE 3 ) was statistically significant so critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety did not create a mediating effect. For junior, IE 1 and IE 3 were statistically significant and positive but IE 2 was not statistically significant. The ratio of the sum of indirect effects to total effect was calculated as 0.28. The mediating role of critical thinking disposition alone and the mediating role of critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety together created partial mediating effect. For senior, similar to freshman, IE 1 was statistically significant and positive but IE 2 and IE 3 were not statistically significant. We found the ratio as 0.27 and reached that critical thinking disposition had partial mediating effect between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement.

Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of this study was to examine the mediating role of critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety in the relationship between pre-service teachers’ cognitive flexibility and academic achievement. This study extended critical thinking disposition and math anxiety to the body of research on cognitive flexibility and academic achievement and enriched the knowledge of how these constructs interact to affect academic achievement. In structural equation model analyzes carried out for this purpose, the five-step structure specified by Hoyle ( 1995 ) was used accordingly: (1) model specification, (2) estimation, (3) evaluation of fit, (4) model modification and (5) interpretation. For freshman, sophomore, junior and senior students, each model was observed to have acceptable or good fit indices in terms of χ 2 /df, SRMR, RMSEA, CFI and TLI (see Table 5 ).

As pointed out in Table 6 , both cognitive flexibility and critical thinking disposition exhibited a direct, positive, and statistically significant effect on academic achievement (H1 and H3, respectively). Moreover, a direct, positive, and statistically significant effect of cognitive flexibility on critical thinking disposition was reported (H2). Cognitive flexibility is one of the cognitive processes that gets in when one starts to think critically (Scheibling-Sève et al., 2022 ). Critical thinking displays a structure associated with cognitive flexibility, which is seen as the ability to adapt to new ones in terms of testing the strengths and weaknesses of different perspectives (Paul, 1990 ). The ability to think critically requires cognitive flexibility since it involves not just focusing on already existing information but also considering other alternatives that are worthwhile exploring, acquiring viewpoints that differ from the initial one, and reconceptualizing a situation (Scheibling-Sève et al., 2022 ). In short, critical thinking necessitates having a wide range of alternatives available for evaluation in our minds. This interactive structure involves selecting and switching between various alternatives of a concept or situation (Jacques & Zelazo, 2005 ). As a result, having low cognitive flexibility can make it more difficult for us to find a solution to a problem or make a decision. Cognitive flexibility opens the door for exhibiting different perspectives in the same situation and avoiding the negative effects of constancy, thus serving as an important tool for critical thinking (Scheibling-Sève et al., 2022 ). When we consider that the disposition for critical thinking is the drive to solve problems, make decisions using the relevant knowledge, and evaluate them (Facione et al., 1998 ), it might be argued that lack of critical thinking skills puts us at risk for making poor decisions and defending beliefs with little substantive evidence (Scheibling-Sève et al., 2022 ). Critical thinking and the disposition to use it, in the view of educational philosophers, should not be one of the alternatives that can be used in the teaching process but rather a fundamental component of education (Norris, 1985 ). Teachers that encourage critical thinking in the classroom have a considerable positive impact on students’ cognitive development and critical thinking dispositions.

Critical thinking is a skill that is desired to be acquired by students with our education system. Despite the importance put on the development of critical thinking skills by the educational system, little is being done to put these skills into practice and to promote their training. Halpern ( 1988 ) asserts that many members of society, particularly teachers, lack sufficient levels of critical thinking. Therefore, critical thinking training for teachers is important so that students could think critically in the classroom and apply what they have learned in new and varied contexts. The critical thinking disposition is linked to cognitive productivity and is thus a component of academic achievement. Similar to the results of our study, Stupnisky et al. ( 2008 ) observed that college students’ critical thinking dispositions predicted their academic achievement. Besides, many studies put forward academic achievement and critical thinking are positively correlated (Abrami et al., 2008 ). In our study, being a relationship between critical thinking disposition and academic achievement is expected situation given the link between critical thinking and disposition toward this skill.

When research works on cognitive flexibility are examined, the outcomes of these studies indicated that cognitive flexibility impacts learning (Jacques & Zelazo, 2005 ) and has a relationship with academic achievement (Kercood et al., 2017 ) because cognitive flexibility allows students to extend their ideas, transfer them to new environments and adjust to contextual changes (Magalhães et al., 2020 ). Increased cognitive flexibility has been linked to lower level of anxiety and higher level of achievement for university students (Timarová & Salaets, 2011 ). The results of the study conducted by Kercood et al. ( 2017 ) showed that academic skills such as reading, math, and writing were significantly predicted by cognitive flexibility. The researchers emphasized a substantial relationship between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement, indicating that cognitive flexibility has extensive effects on academic achievement. Students with high cognitive flexibility may have higher academic achievement as they tend to adapt appropriately alternative approaches to other contexts.

Mathematics anxiety, on the other hand, showed a direct, negative, and statistically significant effect on academic achievement (H5). Furthermore, cognitive flexibility and critical thinking disposition had a direct, negative, and statistically significant effect on mathematics anxiety (H4 and H6, respectively). Cognitive flexibility involves being aware of alternative solutions for adapting different situations and being willing to change. Individuals with higher levels of cognitive flexibility achieve higher performance in decision-making and problem solving (Passolunghi et al., 2016 ). Critical thinking is one of the high-level skills based on mental processes such as logical reasoning, decision-making, and problem-solving and cognitive flexibility affects the development of these skills (Ionescu, 2012 ). This interplay demonstrates the link between cognitive flexibility and critical thinking. Park and Moghaddam ( 2017 ) emphasize the negative effects of anxiety on cognitive flexibility and decision-making process, namely critical thinking. The literature have addressed that flexibility in the use of strategy may be impacted by mathematics anxiety. Students with high math anxiety tend to use inefficient strategies and avoid implementing sophisticated procedures, which makes it difficult to see other strategies, solution procedures and discourage one from trying new approaches (Imbo & Vandierendonck, 2007 ). Thus, this emotion affects academic achievement negatively. It is thought that a negative attitude towards mathematics is related to mathematics anxiety (Lake & Kelly, 2014 ). Since a negative attitude would reduce the effort towards doing mathematics, it affects mathematics achievement in a negative way. Besides, students’ mathematics anxiety, achievement, flexibility were significantly affected by teachers’ mathematics anxiety through negative class experiences created their teachers (Jiang et al., 2021 ). This study highlights the crucial role of teachers and educators should play in assisting students in decreasing their math anxiety and the negative effects of this feeling.

The findings also revealed that critical thinking disposition, cognitive flexibility and mathematical anxiety scores did not significantly differ across grade levels. On one hand, there are studies showing that pre-service teachers’ critical thinking dispositions did not differ depending on grade level in line with this study (Serin et al., 2018 ). On the other hand, some studies have concluded that there is a significant difference in critical thinking dispositions of university students according to the grade level (Kawashima & Shiomi, 2007 ). Moreover, age is a significant predictor of critical thinking disposition for some studies (Dunn et al., 2014 ) but not a significant predictor for some other studies (Thompson et al., 2003 ). In our study, we obtained that there was no significant difference between pre-service teachers’ critical thinking dispositions according to grade level. One could argue that pre-service teachers’ university education did not sufficiently shape their critical thinking dispositions.

The research works show that a large proportion of pre-service teachers have higher mathematics anxiety (Sloan et al., 2002 ). These anxieties experienced by pre-service teachers in mathematics may be due to their previous experiences with mathematics as students, the influence of their teachers or teacher training programs (Raymond, 1997 ). In line with our findings, some studies reveal that grade level is not a significant predictor of mathematics anxiety (Dede & Dursun, 2008 ), despite research showing that students’ anxiety levels increase as grade level increases (Ma, 1999 ) or decreases (Birgin et al., 2010 ). The reason why mathematics anxiety did not significantly change depending on the grade level in our study may be that pre-service teachers do not taking a large-scale exam during their university education and having confidence in their knowledge at this stage.

Finally, when the change in cognitive flexibility is considered in terms of grade level, we attained studies that have outcomes similar to our results (Camcı Erdoğan, 2018 ; Esen-Aygün, 2018 ). In such studies, the cognitive flexibility skills of pre-service teachers did not differ significantly according to the grade level. This could imply that many undergraduate theoretical and applied courses, especially those that foster critical and creative thinking and help students understand alternate possibilities and make decisions, are insufficient (Camcı Erdoğan, 2018 ). According to Esen-Aygün ( 2018 ), it is possible that the skills of cognitive flexibility would not change significantly over the period of the subsequent years of learning experiences as a result of pre-service teachers’ adjustment to the profession of teaching and automatic thinking because cognitive flexibility necessitates a willingness to adapt to new circumstances. However, teachers need to develop a variety of skills to advance their professional capabilities including cognitive flexibility and use them more effectively. Cognitive flexibility is crucial in learning environments since it enables students to simultaneously evaluate knowledge, choose alternate approaches or determine appropriate responses and make use of feedbacks and errors to correct them (Anderson, 2002 ; Ionescu, 2012 ; Magalhães et al., 2020 ). According to some studies, cognitive flexibility begins to evolve quickly in preschool, reaches maturity by age 10 (Blaye et al., 2006 ) and persists in improving throughout adolescence and adulthood (Anderson, 2002 ). Unlike our study results, some studies pointed to increased cognitive flexibility from 5 to 9 years of age (Blaye et al., 2006 ). Magalhães et al. ( 2020 ) found that cognitive flexibility affected students’ scores in grade 4 and grade 6 but not in grade 2. According to the researchers, it points to the growing significance of cognitive flexibility during development. These studies’ findings may differ from those of our study because they mostly focus on younger age groups.

The findings of the current study indicated that the cognitive flexibility has a greater impact on first-year students’ academic achievement than it does on second-year students. Furthermore, the mediating effects of the critical thinking disposition between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were statistically significant, with the exception of the model for sophomore students. Additionally, none of the model estimations of how mathematics anxiety would mediate between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement was statistically significant. Last but not least, for junior students only positive and statistically significant mediating effects of critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were found.

We also found that the mediating effects of critical thinking disposition between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were positive and statistically significant, with the exception of the model for sophomore students (H7). Furthermore, the effects of mathematics anxiety between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were not statistically significant in any of the models (H8). Finally, the mediating effects of critical thinking disposition together with mathematics anxiety between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement were only positive and statistically significant for junior students (H9). There is a standard teaching program in education faculties of the universities in Turkey. The courses in teacher education programs consist of three groups: (1) teaching profession courses, (2) mathematics courses and (3) general culture courses. In the first year of the elementary mathematics education program, there are basic courses such as History, Foreign Language and Information Technologies, as well as mathematics courses such as Fundamentals of Mathematics, Analysis I, Analysis II and Abstract Mathematics, which support the development of pre-service teachers’ basic mathematical skills. In the second year, there are courses such as Linear Algebra, Analysis III, Analytical Geometry and Probability that would support the development of pre-service teachers’ content knowledge. When pre-service teachers reach the third grade level, they take courses such as Teaching Numbers, Teaching Geometry and Measurement, Teaching Algebra and Teaching Probability and Statistics, which aim to improve their knowledge of teaching mathematics. At the fourth grade level, where internship courses such as Teaching Practice I and Teaching Practice II and teaching courses like Problem Solving in Mathematics, Mathematical Modeling and Logical Reasoning come to the fore. For freshman, junior and senior students, critical thinking disposition plays a significant mediating role in the effect of cognitive flexibility on academic achievement. This situation is thought to be due to the fact that the general culture courses taken from different disciplines in the first grade support the different thinking of the students. In the third and fourth grades, pre-service teachers are taught to support different teaching approaches within their mathematics teaching courses. Although a similar conclusion is valid for third and fourth grade levels, the reason why a critical perspective does not have a significant mediating effect on flexible thinking skills on academic achievement for the so-called abstract courses at the second grade level, which is difficult to make sense of, could be related to the content and learning outcomes of these courses. Students who have developed cognitive flexibility in mathematics outperform others in understanding mathematical ideas, using their mathematical expertise, and coming up with creative solutions to problems (Blöte et al., 2001 ; Rittle-Johnson et al., 2012 ). The fact that sophomore students took many courses regarding abstract concepts could be explained by the effect mediated by critical thinking disposition (H7) is not statistically significant only for this grade level. As mentioned before, there is a negative relationship between mathematics anxiety and cognitive flexibility, critical thinking disposition and academic achievement. In this study, it was seen that mathematics anxiety did not have a significant mediating role between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement (H8) across different grades of prospective teachers. A similar situation exists in almost all models in which the mediating role of both mathematics anxiety and critical thinking disposition at the same time is examined (H9). As a result, it can be stated that only the mathematics anxiety variable and both mathematics anxiety and critical thinking disposition do not have a significant mediating role between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement in the context of different grade levels in higher education.

Within the scope of this study, the total and mediating effects between the variables were compared in terms of grade levels. The trend was tried to be determined and accordingly, when the results obtained from the total effect models shared in Fig. 2 are examined, it is seen that the total effect of cognitive flexibility on academic achievement varies over the years, but it reaches the highest effect value for freshman and the lowest effect value for sophomore. There is also an increasing trend in the effect values from sophomore students to senior students (0.580* → 0.328* → 0.410* → 0.443*). When the effects between the variables in the mediating models are examined, it is seen that the direct effect of cognitive flexibility on academic achievement is similar to the tendency in the total effect model over the years (0.246* → 0.192* → 0.215* → 0.239*). The same tendency is also involved in the direct effect of cognitive flexibility on critical thinking disposition (0.442* → 0.279* → 0.353* → 0.400*). However, results that do not show similarity to this trend were also obtained. For example, critical thinking disposition on academic achievement (0.259* → 0.209* → 0.200* → 0.275*), cognitive flexibility on math anxiety (− 0.304* → − 0.210* → − 0.205* → − 0.198*), mathematics anxiety on academic achievement (− 0.224* → − 0.182* → − 0.206* → − 0.181*) and critical thinking disposition on mathematics anxiety (− 0.270* → − 0.225* → − 0.397* → − 0.388*) have different tendencies when the direct effects are concerned. When the trends in mediating models are examined, it is observed that the effect of cognitive flexibility on academic achievement through critical thinking disposition has the highest value for freshman, the lowest value for sophomore, and keep increasing for further grades (0.115* → 0.058 → 0.070* → 0.110*). The effect of cognitive flexibility on academic achievement through math anxiety was not significant at all grade levels (0.068 → 0.038 → 0.042 → 0.036). In the model in which critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety are mediated together, the effect of cognitive flexibility on academic achievement was found to be very low (0.027 → 0.011 → 0.029* → 0.028). When the trend was examined, it was seen that the coefficients in many models had the lowest value at second grade. The reason why cognitive flexibility, critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety have little effect on academic achievement could be related to the content of the mathematics courses at this grade level.

When we consider the mediating roles of the variables (either full mediating, partial mediating or no mediating) over the years, the critical thinking disposition had a partial mediating effect on the effect of cognitive flexibility on academic achievement, except for sophomore students. Mathematics anxiety has no mediating effect at any grade level. Finally, in the model mediated by both critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety, it was seen that there was only a partial mediating effect between cognitive flexibility and academic achievement for junior students.

Limitations and implications

The current research makes a significant contribution to understanding of the relationship among cognitive flexibility, critical thinking disposition, mathematics anxiety and academic achievement as well as the potential mechanism behind this structure. However, it also has some limitations. Since the participants in this study were pre-service teachers, we should tread cautiously when extending the outcomes to younger students. In this study, the data were collected in a single time interval and focused on the correlational structure between the variables. Therefore, inferences for causality could not be made. It is recommended to carry out longitudinal and experimental studies in future research works.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Abrami, P. C., Bernard, R. M., Borokhovski, E., Wade, A., Surkes, M. A., Tamim, R., & Zhang, D. (2008). Instructional interventions affecting critical thinking skills and dispositions: A stage 1 meta-analysis. Review of Educational Research , 78 (4), 1102–1134. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654308326084

Article Google Scholar

Anderson, P. (2002). Assessment and development of executive function (EF) during childhood. Child Neuropsychology , 8 (2), 71–82. https://doi.org/10.1076/chin.8.2.71.8724

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ashcraft, M. H. (2002). Math anxiety: Personal, educational, and cognitive consequences. Current Directions in Psychological Science , 11 (5), 181–185. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.00196

Baroody, A. J. (2003). The development of adaptive expertise and flexibility: The integration of conceptual and procedural knowledge. In A. J. Baroody, & A. Dowker (Eds.), The development of arithmetic concepts and skills: Constructing adaptive expertise (pp. 1–33). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Inc.

Birgin, O., Baloğlu, M., Çatlıoğlu, H., & Gürbüz, R. (2010). An investigation of mathematics anxiety among sixth through eighth grade students in Turkey. Learning and Individual Differences , 20 (6), 654–658. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2010.04.006

Blakey, E., Visser, I., & Carroll, D. J. (2016). Different executive functions support different kinds of cognitive flexibility: Evidence from 2-, 3‐, and 4‐year‐olds. Child Development , 87 (2), 513–526. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdev.12468

Blaye, A., Bernard-Peyron, V., Paour, J., & Bonthoux, F. (2006). Categorical flexibility in children: Distinguishing response flexibility from conceptual flexibility; the protracted development of taxonomic representations. European Journal of Developmental Psychology , 3 (2), 163–188. https://doi.org/10.1080/17405620500412267

Blöte, A. W., Van der Burg, E., & Klein, A. S. (2001). Students’ flexibility in solving two-digit addition and subtraction problems: Instruction effects. Journal of Educational Psychology , 93 , 627–638. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.93.3.627

Boyd, W., Foster, A., Smith, J., & Boyd, W. E. (2014). Feeling good about teaching mathematics: Addressing anxiety amongst preservice teachers. Creative Education , 5 , 207–217. https://doi.org/10.4236/ce.2014.54030

Brady, P., & Bowd, A. (2005). Mathematics anxiety, prior experience, and confidence to teach mathematics among preservice education students. Teachers and Teaching: Theory and Practice , 11 (1), 37–46. https://doi.org/10.1080/1354060042000337084

Camcı Erdoğan, S. (2018). A research on the cognitive flexibility skills of prospective teachers for gifted students. Manisa Celal Bayar Üniversitesi Journal of Social Sciences , 16 (3), 77–96.

Google Scholar

Çelikkaleli, Ö. (2014). The validity and reliability of the cognitive flexibility scale. Education and Science , 39 (176), 339–346. https://doi.org/10.15390/EB.2014.3466

Dede, Y., & Dursun, Ş. (2008). An investigation of primary school students’ mathematics anxiety levels. Uludağ University Faculty of Education Journal , 21 (2), 295–312.

Dunn, K. E., Rakes, G. C., & Rakes, T. A. (2014). Influence of academic self-regulation, critical thinking, and age on online graduate students’ academic help-seeking. Distance Education , 35 (1), 75–89. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2014.891426

Eden, C., Heine, A., & Jacobs, A. M. (2013). Mathematics anxiety and its development in the course of formal schooling-A review. Psychology , 4 (6A2), 27–35. https://doi.org/10.4236/psych.2013.46A2005

Ennis, R. H. (1985). A logical basis for measuring critical thinking skills. Educational Leadership , 43 (2), 44–48

Ertaş-Kılıç, H., & Şen, A. I. (2014). Turkish adaptation study of UF/EMI critical thinking disposition instrument. Education and Science , 39 (176), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.15390/EB.2014.3632

Esen-Aygün, H. (2018). The relationship between pre–service teachers’ cognitive flexibility and interpersonal problem solving skills. Eurasian Journal of Educational Research , 77 , 105–128.

Facione, P. A., Facione, N. C., & Giancarlo, C. A. (1998). The California critical thinking Disposition Inventory Test Manual (revised) . California Academic Press.

Facione, P. A., Facione, N. C., & Giancarlo, C. A. (2000). The disposition toward critical thinking: Its character, measurement, and relationship to critical thinking skill. Informal Logic , 20 (1), 61–84. https://doi.org/10.22329/il.v20i1.2254

Geary, D. C., Hoard, M. K., & Nugent, L. (2023). Boys’ advantage in solving algebra word problems is mediated by spatial abilities and mathematics anxiety. Developmental Psychology , 59 (3), 413–430. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001450

Gresham, G. (2018). Preservice to inservice: Does mathematics anxiety change with teaching experience? Journal of Teacher Education , 69 (1), 90–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/00224871177025

Güner, P., & Gökçe, S. (2021). Linking critical thinking disposition, cognitive flexibility and achievement: Math anxiety’s mediating role. The Journal of Educational Research , 114 (5), 458–473. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.2021.1975618

Halpern, D. F. (1988). Assessing student outcomes for psychology majors. Teaching of Psychology , 15 (4), 181–186. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328023top1504_1

Hoyle, R. H. (1995). Structural equation modeling: Concepts, issues, and applications . Sage

Ikegulu, T. N. (1998). An empirical development of an instrument to assess mathematics anxiety and apprehension . Retrieved from https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED433235.pdf

Imbo, I., & Vandierendonck, A. (2007). The development of strategy use in elementary school children: Working memory and individual differences. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology , 96 (4), 284–309. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2006.09.001

Ionescu, T. (2012). Exploring the nature of cognitive flexibility. New Ideas in Psychology , 30 (2), 190–200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.newideapsych.2011.11.001

Jacques, S., & Zelazo, P. D. (2005). Language and the development of cognitive flexibility: Implications for theory of mind. In J. Astington, & J. Baird (Eds.), Why language matters for theory of mind (pp. 144–162). Oxford University Press.

Jiang, R., Liu, R., Star, J., Zhen, R., Wang, J., Hong, W., Jiang, S., Sun, Y., & Fu, X. (2021). How mathematics anxiety affects students’ inflexible perseverance in mathematics problem-solving: Examining the mediating role of cognitive reflection. British Journal of Educational Psychology , 91 (1), 237–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12364

Kawashima, N., & Shiomi, K. (2007). Factors of the thinking disposition of Japanese high school students. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal , 35 (2), 187–194. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2007.35.2.187

Kercood, S., Lineweaver, T. T., Frank, C. C., & Fromm, E. D. (2017). Cognitive flexibility and its relationship to academic achievement and career choice of college students with and without attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Postsecondary Education and Disability , 30 (4), 329–344.

Kline, R. B. (2011). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling . The Guilford Press

Lake, V., & Kelly, L. (2014). Female preservice teachers and mathematics: Attitudes, beliefs, and stereotypes. Journal of Early Childhood Teacher Education , 35 , 262–275. https://doi.org/10.1080/10901027.2014.936071

Ma, X. (1999). A meta-analysis of the relationship between anxiety toward mathematics and achievement in mathematics. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education , 30 (5), 520–541. https://doi.org/10.2307/749772

Magalhães, S., Carneiro, L., Limpo, T., & Filipe, M. (2020). Executive functions predict literacy and math achievements: The unique contribution of cognitive flexibility in grades 2, 4, and 6. Child Neuropsychology: A Journal on Normal and Abnormal Development in Childhood and Adolescence , 26 (7), 934–952. https://doi.org/10.1080/09297049.2020.1740188

Maldonado Moscoso, P. A., Anobile, G., Primi, C., & Arrighi, R. (2020). Math anxiety mediates the link between number sense and Math achievements in high Math anxiety young adults. Frontiers in Psychology , 11 , 1095. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.01095

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Maloney, E. A., & Beilock, S. L. (2012). Math anxiety: Who has it, why it develops, and how to guard against it. Trends in Cognitive Sciences , 16 (8), 404–406. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2012.06.008

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., Artelt, C., Baumert, J., & Peschar, J. L. (2006). OECD’s brief self-report measure of educational psychology’s most useful affective constructs: Cross-cultural, psychometric comparisons across 25 countries. International Journal of Testing , 6 (4), 311–360. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327574ijt0604_1 .

McClelland, M. M., Cameron, C. E., Duncan, R., Bowles, R. P., Acock, A. C., Miao, A., & Pratt, M. E. (2014). Predictors of early growth in academic achievement: The head-toes-knees-shoulders task. Frontiers in Psychology , 5 , 599. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00599

McLean, J. F., & Hitch, G. J. (1999). Working memory impairments in children with specific arithmetic learning difficulties. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology , 74 (3), 240–260. https://doi.org/10.1006/jecp.1999.2516

Norris, S. P. (1985). Synthesis of research on critical thinking. Educational Leadership , 42 (8), 40–45.

Park, J., & Moghaddam, B. (2017). Impact of anxiety on prefrontal cortex encoding of cognitive flexibility. Neuroscience , 345 , 193–202. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2016.06.013

Passolunghi, M. C., Caviola, S., De Agostini, R., Perin, C., & Mammarella, I. C. (2016). Mathematics anxiety, working memory, and mathematics performance in secondary-school children. Frontiers in Psychology , 7 , 42. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.00042

Paul, R. W. (1990). Critical thinking . Sonoma State University.

Purpura, D. J., Schmitt, S. A., & Ganley, C. M. (2017). Foundations of mathematics and literacy: The role of executive functioning components. Journal of Experimental Child Psychology , 153 , 15–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jecp.2016.08.010

Raymond, A. M. (1997). Inconsistency between a beginning elementary school teacher’s mathematics beliefs and teaching practice. Journal for Research in Mathematics Education , 28 (5), 550–576. https://doi.org/10.5951/jresematheduc.28.5.0550

Rittle-Johnson, B., Star, J. R., & Durkin, K. (2012). Developing procedural flexibility: Are novices prepared to learn from comparing procedures? British Journal of Educational Psychology , 82 , 436–455. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.2011.02037.x

Rosseel, Y. (2012). Lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software , 48 , 1–36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Rudd, R. D. (2007). Defining critical thinking. Techniques: Connecting Education and Careers , 82 (7), 46–49.

Rueda, M. R., Posner, M. I., & Rothbart, M. K. (2005). The development of executive attention: Contributions to the emergence of self-regulation. Developmental Neuropsychology , 28 (2), 573–594. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326942dn2802_2

Scheibling-Sève, C., Pasquinelli, E., & Sander, E. (2022). Critical thinking and flexibility. In E. Clément (Ed.), Cognitive flexibility: The cornerstone of learning (pp. 77–112). ISTE Ltd and Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119902737.ch4

Serin, M. K., Uyanık, G., & Incikabı, L. (2018). The relationship between pre-service primary school teachers’ beliefs about mathematics and critical thinking dispositions. Turkish Journal of Computer and Mathematics Education , 9 (3), 513–535.

Sireci, S., Han, K. T., & Wells, C. S. (2008). Methods for evaluating the validity of test scores for English language learners. Educational Assessment , 13 (2–3), 108–131. https://doi.org/10.1080/10627190802394255 .

Sloan, T., Daane, C. J., & Giesen, J. (2002). Mathematics anxiety and learning styles: What is the relationship in elementary preservice teachers? School Science and Mathematics , 102 (2), 84–87. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1949-8594.2002.tb17897.x

Spiro, R. J., Feltovich, P. J., Jacobson, M. J., & Coulson, R. L. (1992). Cognitive flexibility, constructivism, and hypertext: Random access instruction for advanced knowledge acquisition in ill-structured domains. In T. M. Duffy, & D. Jonassen (Eds.), Constructivism and the technology of instruction: A conversation (pp. 57–75). Erlbaum.

Stad, F. E., Van Heijningen, C. J., Wiedl, K. H., & Resing, W. C. (2018). Predicting school achievement: Differential effects of dynamic testing measures and cognitive flexibility for math performance. Learning and Individual Differences , 67 , 117–125.

Star, J. R., & Newton, K. J. (2009). The nature and development of experts’ strategy flexibility for solving equations. Zdm Mathematics Education , 41 , 557–567. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-009-0185-5

Stupnisky, R. H., Renaud, R. D., Daniels, L. M., Haynes, T. L., & Perry, R. P. (2008). The interrelation of first-year college students’ critical thinking disposition, perceived academic control, and academic achievement. Research in Higher Education , 49 , 513–530. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-008-9093-8 .

Sugiura, Y. (2013). The dual effects of critical thinking disposition on worry. PloS One , 8 (11), e79714. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0079714

Thompson, S. D., Martin, L., Richards, L., & Branson, D. (2003). Assessing critical thinking and problem solving using a web-based curriculum for students. Internet and Higher Education , 6 , 185–191. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1096-7516(03)00024-1

Timarová, S., & Salaets, H. (2011). Learning styles, motivation and cognitive flexibility in interpreter training: Self-selection and aptitude. Interpreting , 13 (1), 31–52. https://doi.org/10.1075/intp.13.1.03tim

Zhang, L. F. (2003). Contributions of thinking styles to critical thinking dispositions. The Journal of Psychology , 137 (6), 517–543. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980309600633

Zhang, D., & Wang, C. (2020). The relationship between mathematics interest and mathematics achievement: Mediating roles of self-efficacy and mathematics anxiety. International Journal of Educational Research , 104 , 101648. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2020.101648

Download references

Open access funding provided by the Scientific and Technological Research Council of Türkiye (TÜBİTAK). No funding was received for conducting this study.

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Department of Mathematics and Science Education, Niğde Ömer Halisdemir University, Niğde, Turkey

Semirhan Gökçe

Department of Mathematics and Science Education, Istanbul University-Cerrahpaşa, İstanbul, Turkey

Pınar Güner

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Semirhan Gökçe .

Ethics declarations

Conflict of interest.

The author(s) declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Publisher’s note.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Rights and permissions

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ .

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Gökçe, S., Güner, P. Pathways from cognitive flexibility to academic achievement: mediating roles of critical thinking disposition and mathematics anxiety. Curr Psychol (2024). https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05642-0

Download citation

Accepted : 08 January 2024

Published : 20 January 2024

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-024-05642-0

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Teacher education

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

IMAGES

VIDEO

COMMENTS

The Academic Emotions Questionnaire (Pekrun, Goetz, & Frenzel, 2005) was used to assess how specific negative academic emotions mediated the effect of critical thinking on achievement. Results ...

The Academic Emotions Questionnaire (Pekrun, Goetz, & Frenzel, 2005) was used to assess how specific negative academic emotions mediated the effect of critical thinking on achievement. Results showed that critical thinking was positively associated with achievement, but negative emotions (anger, anxiety, shame, boredom, and hopelessness) were ...

The study tested the control-value theory's (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun, Goetz, Titz, & Perry, 2002) assumptions regarding the cognitive-motivational effects of emotions on achievement. Specifically, the link between critical thinking and achievement was examined among 220 engineering students. The Academic Emotions Questionnaire (Pekrun, Goetz, & Frenzel, 2005) was used to assess how specific ...

Critical Thinking, Negative Academic Emotions, and Achievement: A Mediational Analysis Felicidad T. Villavicencio. Discipline: Education Abstract: The study tested the control-value theory's (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun, Goetz, Titz, & Perry, 2002) assumptions regarding the cognitive-motivational effects of emotions on achievement.

The study tested the control-value theory's (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun, Goetz, Titz, & Perry, 2002) assumptions regarding the cognitive-motivational effects of emotions on achievement. Specifically, the link between critical thinking and achievement was examined among 220 engineering students. The Academic Emotions Questionnaire (Pekrun, Goetz, & Frenzel, 2005) was used to assess how specific ...