Japanese Multidimensional Problem Solving

In the West, the standard approach for problem solving is to take a good look a the problem, after which a solution approach will pop into someone’s head. This approach is then optimized until the problem is solved. However, while this often ends up with one solution, it usually is far from the best solution possible. In Japan, a very different multidimensional problem-solving approach is common. Rather than just use any solution that solves the problem, they aim for the best solution they can find.

There are a number of well-known Japanese problem-solving techniques for managing issues and finding their root cause. This post will focus on the multidimensional decision used to find a solution, which is surprisingly simple and highly successful but still mysterious to many westerners.

Problem-Solving Environment

Let’s first review a few of the well-known methods in the Japanese problem-solving toolbox:

Problem Solving Overview: A3

The A3 is named after an A3 sheet of paper, since the goal is to fit all information related to the problem solving on one sheet of paper. Ideally, the sheet should be a working document and hence handwritten, but in the West a computer document is often preferred. There is no fixed list of points that go on the A3, but it usually includes:

- A description of the problem

- The current state

- The goal of the problem solving

- A root cause analysis

- A progress status

- Confirmation of problem solution

- Organizational information like responsible parties, date, approval, etc.

Root Cause: 5 Whys

The 5 Whys method is based on Taiichi Ohno’s approach, at Toyota, of asking “Why?” five times in a row. The goal is not to accept the first answer but rather to dig deeper to fully understand the root cause of the problem.

Root Cause: Fishbone Diagram

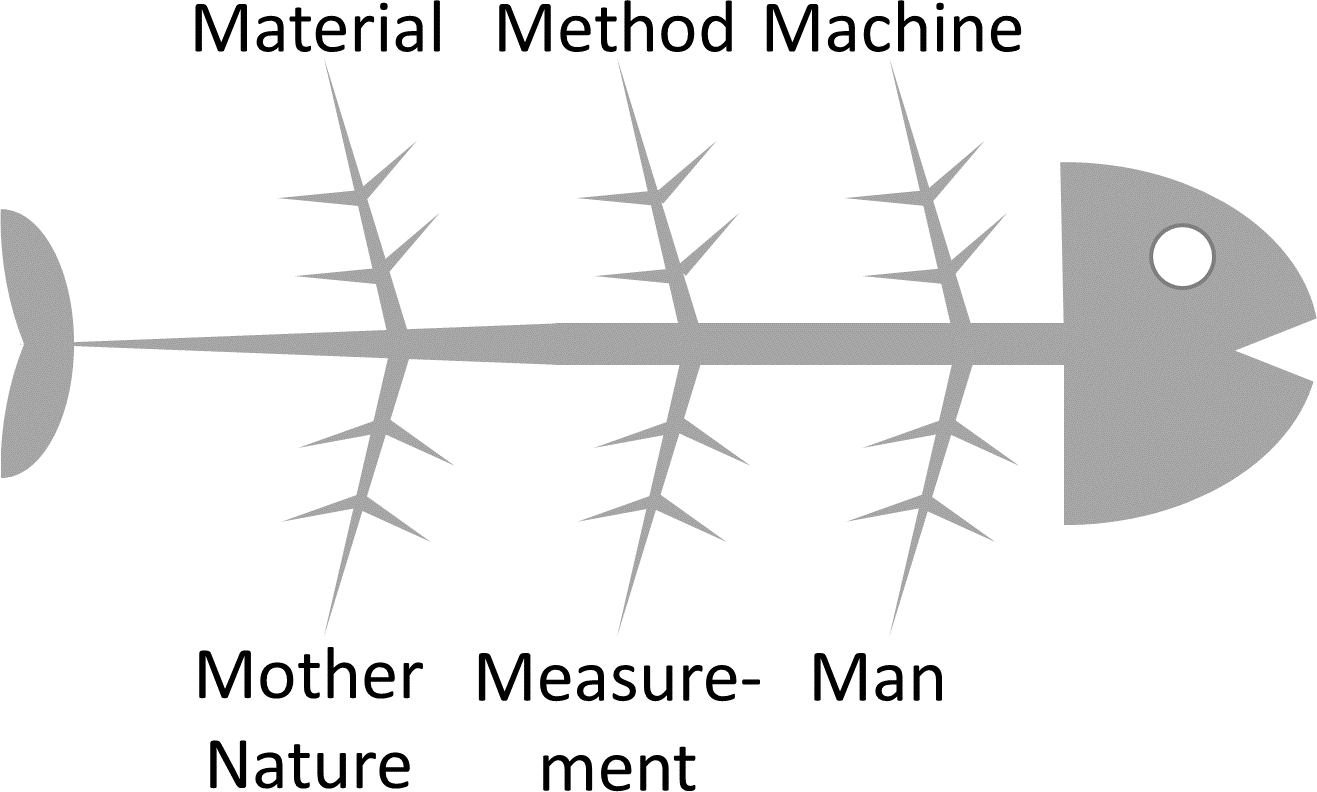

Finally, there is the Fishbone Diagram , also known as the herring-bone diagram or cause-and-effect diagram . If you want to sound fancy, you could also say Ishikawa Diagram . Few people will understand, but it makes you look impressive. The aim is to address the problem from multiple different directions, graphically represented by a fishbone. The head is the problem, and the bones are the individual possible causes that are analyzed. The causes can be specific to the particular problem, but in industry, the following are also common:

- Measurement

- Mother Nature

As said above, in the Western world one problem solution is selected and then optimized until it solves the problem. However, in Japan, an approach with a multitude of different solutions is common. Especially for complex problems, this multidimensional approach yields much better results than a Western uni-dimensional way.

Let’s take, for example, the development of the Toyota Prius hybrid gasoline–electric vehicle. The goal of Toyota was to develop a new highly environmentally friendly vehicle. Western car makers had long ago decided to pursue the hydrogen fuel cell as the basis for such vehicles, and spent many years in vain trying to get those vehicles functioning well even as prototypes.

Toyota, on the other hand, did not decide what type of vehicle they wanted upfront. Rather, under the leadership of Takehisa Yaegashi, they evaluated different design possibilities. In their first round, they looked at a whopping eighty different possibilities to power the car, including electric, gasoline–electric hybrid, diesel–electric hybrid, high-efficiency diesel engines, high-efficiency gasoline engines, liquid hydrogen fuel cells, gaseous hydrogen fuel cells, and many more.

They evaluated each one to some extent before they selected around thirty design options that had more potential. These thirty designs then went into the next round, with more detailed analysis, simulations, and evaluations, and were narrowed down to the ten designs that went into the last round. Those ten designs were each looked at in even more detail with even more analyses, and then the gasoline–electric hybrid emerged as the winner and the power system for the Prius model.

The resulting product was a wild success for Toyota. While other well-established car companies with years of fuel-cell research initially laughed at the weird concept, they didn’t laugh for long. The Prius became a bestseller, within two years even a profitable bestseller, and it gave a huge boost to Toyota’s image as advanced and eco-friendly. Other car makers then scrambled to copy the success, but they are still one to two years behind Toyota with their vehicles.

Do I have to come up with eighty different solutions for all my problems now?

Of course, the size of the solution space and the effort put into has to be in reason with the size of the problem. The development of a new car costs between one and six billion dollars (that’s right, billion, not million). Hence, before investing enough money to buy a small country, it is well worth it to evaluate all options before placing your bet.

On the other hand, if your problem is smaller, you may work with fewer design evaluations. One problem where I have repeatedly used this approach with much success is organizing the layout of a plant or a plant section. Rather than moving all hardware around on a floor plan until it fits, I prefer to create different plans instead.

Using a multi-functional team with members from management, operations, planning, and production, I create multiple solutions. If the team is large enough, I even split them into groups of three to four people (a great size for teamwork) and have them create designs independently . Hence, I end up with two or thee designs in the first round. I intentionally keep the members on a very tight schedule, since at this stage I want only a rough sketch rather than a detailed and installation-ready plan. Thirty to sixty minutes is plenty for this purpose.

Next, we compare the designs, pushing people along the learning curve for this particular layout problem. Afterward the teams are mixed and given certain requirements for the second round. In my experience, after two rounds with four to six different designs, the teams have explored the possible design space much better than they possibly could have with a single design.

As a next step, we could either select the winner (inevitably one of the designs from the last row), or—my preference—have all team members come together and build the best design based on the four to six designs we have so far. Overall, with less than ten people and less than one workshop day, we create a new shop floor layout that everybody feels good with and that incorporates the best ideas out of multiple designs.

I have personally used this multidimensional approach to problem solving successfully for many different problems, including shop floor layout, part design, information flow design, efficiency improvements, and many more. This approach has never failed me.

I sincerely hope that this method will also help you with your daily work, and I wish you much success. Now, go out and improve your Industry.

6 thoughts on “Japanese Multidimensional Problem Solving”

This post very succinctly goes beyond the machine-like application of “success” tools and shows that it all depends on working together.

“succinctly” … such a beautiful word 🙂

Thanks for the praise!

Great effort and innovative techniques !! Welldone dear.

Great and insightful

Innovative techniques and just class

Easy solution techichque and just class

Leave a Comment

Notify me of new posts by email.

A Japanese Problem-Solving Approach: The KJ Ho Method

- Conference paper

- First Online: 01 January 2016

- Cite this conference paper

- Susumu Kunifuji 4

Part of the book series: Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing ((AISC,volume 364))

1151 Accesses

8 Citations

In Japan, by far the most popular creative problem-solving methodology using creative thinking is the KJ Ho method. This method puts unstructured information on a subject matter of interest into order through alternating divergent and convergent thinking steps. In this paper, we explain basic procedures associated with the KJ Ho and point out some of its most specific applications.

KICSS’2013 Invited Lecture [ 6 ].

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

Google Scholar

Kawakita, J.: The Original KJ Method, Revised edn. Kawakita Research Institute (1991)

Kunifuji, S.: A Japanese problem solving approach: the KJ-Ho (Method). In: Skulimowski, A.M.J. (ed.) Looking into the Future of Creativity and Decision Support Systems: Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Knowledge, Information and Creativity Support Systems, Kraków, Poland, 7–9 Nov 2013 (Invited lecture). Advances in Decision Sciences and Future Studies, vol. 2, pp. 333−338. Progress & Business Publishers, Kraków (2013)

Kunifuji, S., Kato, N., Wierzbicki, A.P.: Creativity support in brainstorming. In: Wierzbicki, A.P., Nakamori, Y. (eds.) Creative Environment: Issues of Creativity Support for the Knowledge Civilization Age, Studies in Computational Intelligence (SCI) vol. 59, pp. 93−126. Springer (2007)

Naganobu, M., Maruyama, S., Sasase M., Kawaida S., Kunifuji S., Okabe A. (the Editorial Party of Field Science KJ Ho): Exploration of Natural Fusion, Thought and Possibility of Field Science. Shimizu-Kobundo-Shobo, Japan (in Japanese) (2012) (Note: Published as a Kawakita Jiro Memorial Collection issue covering various topics of Fieldwork Science and the KJ Ho)

Viriyayudhakorn, K.: Creativity assistants and social influences in KJ-method creativity support groupware. Dissertation of School of Knowledge Science, JAIST, Mar 2013

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Japan Advanced Institute for Science and Technology, Kanazawa, Japan

Susumu Kunifuji

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Susumu Kunifuji .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Department of Automatic Control and Biomedical Engineering, AGH University of Science and Technology, Kraków, Poland, and International Centre for Decision Sciences and Forecasting, Kraków, Poland

Andrzej M.J. Skulimowski

Polish Academy of Sciences, Systems Research Institute, Warszawa, Poland, and AGH University of Science and Technology, Kraków, Poland

Janusz Kacprzyk

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2016 Springer International Publishing Switzerland

About this paper

Cite this paper.

Kunifuji, S. (2016). A Japanese Problem-Solving Approach: The KJ Ho Method. In: Skulimowski, A., Kacprzyk, J. (eds) Knowledge, Information and Creativity Support Systems: Recent Trends, Advances and Solutions. Advances in Intelligent Systems and Computing, vol 364. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19090-7_13

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-19090-7_13

Published : 26 February 2016

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-319-19089-1

Online ISBN : 978-3-319-19090-7

eBook Packages : Computer Science Computer Science (R0)

Share this paper

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

Saihatsu Boshi – Key to Japanese problem-solving

The Japanese are well-known to be perfectionists in various aspects of their work. Non-Japanese who work with them, either as employees or suppliers, need to be familiar with one of the key techniques they use for pursuing perfection, “ saihatsu boshi .”

Translated literally, this means “prevention of reoccurrence.” But the simplicity of this phrase belies the deep significance it has for many Japanese. Of course, people everywhere can agree that making sure problems don’t happen again is a good thing. However, the Japanese have developed a structured process for doing this. And they often express frustration when working with people from other cultures who do not take this approach and thus run the risk of the same problems cropping up again. In Japan, saihatsu boshi is simply accepted standard behavior, and anything else would suggest unprofessionalism or lack of commitment. Thus, in order to optimize their relationships with Japanese, it’s useful for non-Japanese to adopt this technique.

The first step in saihatsu boshi is “ genin wo mitsukeru “, which translates as getting to the root of the problem, or discovering the root cause. This process is what Americans might refer to as a detailed post-mortem analysis. It involves looking at all the possible reasons why something went wrong, and identifying specifically what factors led to the failure, mistake, problem, or defect. A vague answer like “it was human error” or “it was a random glitch” are deemed unacceptable.

In many non-Japanese cultures, this root cause analysis is difficult because individuals are not comfortable being forthright about their errors that led to a problem. This is because in many cultures, admitting a mistake can be viewed as a weakness, be acutely embarrassing, or cause one to be the target of punishment or even dismissal. In the Japanese environment, however, people are expected to put aside their pride in the pursuit of perfection and the common good. The lifetime employment custom also makes it safer for people to be forthright about instances where their performance was not perfect, because they won’t fear being let go as a result.

Once the root cause has been identified, “ taisaku ” – countermeasures – need to be put in place. This is true no matter how difficult to control or rarely-occurring a root cause might be. For example, if you have identified your root cause as a simple mistake made by someone on the production line, your countermeasure might involve instituting double-check procedures, adding additional inspection staff at the end of the line, or altering the operator’s job so that fatigue or distractions are reduced.

As an example of the Japanese demand for countermeasures even in situations where they might seem impossible, one of my clients lost a boatload of product headed toward the U.S. when the ship carrying it hit a typhoon and sank to the bottom of the Pacific. The company was infuriated when the shipping firm seemed unable to come up with a countermeasure. From the shipping company’s perspective, typhoons are not something that humans can do anything about. But from the Japanese perspective, anything can be countermeasured. Perhaps the shipping company could build ships with thicker hulls, or buy more accurate weather forecasting equipment. When the shipping company did not produce a countermeasure, it irreparably damaged its relationship with its Japanese client.

And here lies one of the morals of this story: in Japanese eyes, any mistake or failure is of course a huge negative. But if you can produce a good root cause analysis and corresponding countermeasures, you can often get a second chance. The damage from not doing this kind of saihatsu boshi can be worse than from the initial mistake or problem. Japanese feel that although having a problem is a bad thing, letting the same problem happen again is even worse.

In this sense , saihatsu boshi is all about organizational learning – the ability for a company to absorb the lessons of its own experience. Saihatsu boshi is a way of ensuring that individuals and the entire organization will learn from things that go wrong, and change its ways of doing things so that they will never be repeated. The countermeasures created in the saihatsu boshi process usually consist of improvements in processes and procedures. Thus, saihatsu boshi is really the backbone of the vaunted Japanese ability to do kaizen (continuous improvement.)

Here’s one more example of saihatsu boshi . I was using a Japanese-owned translation company as a subcontractor. I had asked them to prepare a translation for a client, and send it to them by Federal Express immediately before leaving on a trip to Japan. When I returned from Japan, I called the client to discuss the document, which they were supposed to have been reviewing while I was gone, only to discover that they had never received it. Upon investigation, it turned out that the Federal Express had been duly delivered to the company, but was misrouted by the mailroom staff and had never made it to my counterpart’s desk. In this situation, many American suppliers would have said “it wasn’t our fault” and the case would be closed. However, I received a phone call from the Japanese who runs the translation company, saying how he didn’t want me to have to worry about a repeat of this kind of problem. So he would institute a new procedure: anytime they sent a Federal Express to one of my clients in the future, they would always make a follow-up call the next day to make sure that they had received it. From my perspective, this was customer service above-and-beyond the call of duty, but when I told him so, he was surprised that I thought so. From his point of view, implementing a countermeasure when something had gone wrong was standard operating procedure. Imagine the consternation of a Japanese who is used to being dealt with in this way when faced with a “it’s out of our hands” kind of approach.

So, let’s say that something has gone wrong or there is some problem in the work you have been doing with Japanese. What’s the best way to address it using the saihatsu boshi technique? First, show your intention to do saihatsu boshi by saying something like “we want to make sure this doesn’t happen again”, “we want to prevent a reoccurrence of this problem”, or “we want to be sure to avoid this kind of problem in the future.” Then, describe in detail the root cause or causes. Even when dealing with someone of higher rank than you or a client, being honest about the root causes is extremely important. This willingness to be forthright, even about your own mistakes or failures, will be valued. Then, for each root cause, describe in detail what countermeasure or countermeasures you plan to adopt. Finally, finish with a reaffirmation of your commitment to avoiding having this same problem happen again, and your desire for a continued good working relationship.

Other articles you may be interested in:

HORENSO – (REPORT, CONTACT AND CONSULT)

GENIN TSUIKYU – JAPANESE BUSINESS GETS TO THE ROOT OF THE MATTER

SAIHATSU BOSHI – “THOSE WHO FORGET THE MISTAKES OF THE PAST ARE DOOMED TO REPEAT THEM”

Related articles

New approaches needed by Japanese companies to Generation Z

Judging by this article in the Nikkei Business magazine (¥), many of the concerns and valu

(Video) So, What is Monozukuri Actually?

Monozukuri is one of those well-known and often used Japanese words among people from outside of Jap

(Video) So, What is Ikigai Actually?

Ikigai - The Japanese word for the goal that gets you going - is often misunderstood by non-Japanese

What can we help you achieve?

- Privacy Overview

- Strictly Necessary Cookies

- Cookie Policy

This website uses cookies so that we can provide you with the best user experience possible. Cookie information is stored in your browser and performs functions such as recognising you when you return to our website and helping our team to understand which sections of the website you find most interesting and useful.

Strictly Necessary Cookie should be enabled at all times so that we can save your preferences for cookie settings.

If you disable this cookie, we will not be able to save your preferences. This means that every time you visit this website you will need to enable or disable cookies again.

More information about our Privacy Policy

- > Kaizen: The Japanese Management Style to Continuous Improvement

Kaizen: The Japanese Management Style to Continuous Improvement

Posted by Morgan Wright

Dec 29, 2022 11:43:01 AM

The Japanese word Kaizen is often used interchangeably with the idea of continuous improvement. The Japanese character kai means change, and the character zen means good. Thus, Kaizen is good change.

Even though Kaizen is a Japanese idea, many companies in the US have implemented it with great success by joining the best of traditional Japanese management practices with the strengths of Western businesses. By combining the benefits of teamwork with the individual's creativity, the best of both worlds results. Kaizen is closely associated with lean manufacturing in the West because continuous improvement combined with just-in-time manufacturing principles form the foundation of lean.

The History of Continuous Improvement in Japan

After World War II, the United States wanted to encourage Japan to rebuild. General MacArthur asked several leading experts from the US to visit Japan and advise them on how to ignite the rebuilding process. One of these experts was Dr. W. Edward Deming . Dr. Deming was a statistician who had been engaged in census work. His goal in Japan was to set up a census. While here, he honed in on some of the challenges being experienced by the newly emerging industries. Many Japanese manufacturing companies faced massive difficulties, often lacking investment capital, raw materials, and components. On top of this, the morale of the nation and workforce was low. Based on his experience, Deming had some advice to give.

During the 1950's Dr. Deming visited Japan regularly. He helped Japanese businesses transition from a focus on results to one on processes. He taught leaders to concentrate the efforts of everyone on continuous improvement and rooting out imperfection at every point of the operation. Many Japanese manufacturers embraced Dr. Deming's advice, and by the 1970s, they were reaping the benefits. The most famous result is the Toyota Production System, which led to many business improvement practices used heavily in Japan, including just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing and Total Quality Management (TQM).

Although much of the foundation of the Japanese approach to continuous improvement originated in America, Western manufacturers showed little interest in operationalizing it until the late 1970s and early 80s. At that point, the success of Japanese manufacturing caused other organizations to take note and reassess their approach. Thus, Kaizen begins to emerge in the US along with increased use of TQM and JIT. Management consultants in the US generally use the term Kaizen to cover a wide range of improvement practices primarily regarded as Japanese.

The 4 Principles of Kaizen

The following principles provide the "How to" for Kaizen.

Every process can be improved. Kaizen thinking is based on the idea that even a process that produces acceptable outputs can be improved. Waste reduction is an excellent example. A process may have amazing results, but if it uses more resources than are needed to provide value to the customer, it should be a target for improvement.

Defects and process failures are usually the results of imperfect processes, not people. It is easy to blame people for problems, but closer inspection often reveals that problems were inevitable because the design of the process was flawed.

Every person in the organization must have a role in improvement. Kaizen is all about employee inclusion in improvement and problem-solving. The people closest to your customers, processes, and products are in the best position to identify opportunities for improvement.

Small changes can have a significant impact. It is not necessary to implement revolutionary change to improve. Instead, the Kaizen mentality is about noticing and resolving minor impediments on the path to perfection.

Other Japanese Quality Management Terms

While Kaizen is the most widely used Japanese continuous improvement concept, some other quality management and problem-solving ideas have made their way from Japan to the US.

Muri: One of the first things that plant managers engaging in improvement focus on is called Muri. Muri translates to "totally unreasonable." It happens when employees or machines are pushed past a reasonable limit that overburdens them and slows down rather than speeds up a process.

Mura: Mura roughly translates to "inconsistency." Mura happens when there is variation in a standard process. Manufacturers can address Mura by analyzing production and sales patterns to better anticipate customer demand and adjust production accordingly.

Muda: In English, Muda means "waste" or "wasteful activity." If an organization can reduce Muda, it can increase productivity and, therefore, profits. The Toyota Production System identifies seven types of waste including:

● Transport

● Inventory

● Overproduction

● Over-processing

Other organizations also include the waste of human potential.

Poka-Yoke: Another element of the Toyota Production System is Poka-Yoke which means creating error-proof processes. It is often a step built into the process to notify the operator of a problem that requires immediate corrective or preventative action.

Kata : Kata translates to "the form and order of doing things." Ideas about doing things in the correct and appropriate order are deeply entrenched in Japanese culture. Therefore, rather than jumping in to fix a problem with little information or insight, Kata encourages thinking before doing.

Gemba: The word Gemba means "the real place," in manufacturing, it typically refers to the shop or plant floor. In other industries, it might mean the office, the classroom, or the construction site. During a Gemba Walk , team members go to the place where work is done to show respect, ask questions, and observe processes in action.

Kanban: Kanban is a planning tool developed by Toyota to manage material replenishment in a just-in-time production environment. The term comes from the Japanese words for card and signal. Today it is used to visualize the movement of materials, information, and work in a multitude of environments.

Japanese continuous improvement ideas have resulted in great success for many US firms. Adopting the Kaizen mentality can have an enormous impact on the results of business processes of all sorts. With a focus on employee inclusion and problem-solving, even daunting challenges can be overcome.

Topics: Kaizen

Add a Comment

Subscribe via email, recent posts.

- Our Customers

Why KaiNexus

- Collaboration

- Standardization

- Customer Success Manager

- Lean Strategy

- Solutions Engineering

- Customer Marketing

- Configuration

- Continuous Enhancements

- Employee Driven

- Leader Driven

- Strategy Development

- Process Driven

- Daily Huddles

- Idea Generation

- Standard Work

- Visual Management

- Advanced ROI

- Notifications

- Universal Badges

- Case Studies

- Education Videos

Copyright © 2024 Privacy Policy

Oxford Education Blog

The latest news and views on education from oxford university press., teaching for learning: the japanese approach – geoffroy wake.

Lesson Study in Japan is a model of teacher-led research in which a group of teachers collaborate to target a particular area for development in their students’ learning. Based on their prior teaching, the group of teachers work together to research, plan, teach and observe a series of lessons, using ongoing discussion, reflection and expert input to monitor and improve their teaching.

Here in the U.K., as elsewhere in the world, there is a lot of interest in Lesson Study as a mode of professional learning, which quite often focuses on mathematics. However, there are many variations on a theme emerging, and there is a danger that the true essence of what showed initial promise might become corrupted.

The first step to ensure this is mitigated against is to really understand the fundamentals of what constitutes high quality in the innovation.

My research with colleagues, both in our Centre for Research in Mathematics Education in Nottingham and at the Tokyo Gakugei University in Japan, suggests that the Lesson Study should be informed by expert knowledge of the curriculum and carefully structured practitioner research.

Importantly, at the very centre of the process is a well posed question that asks how we might better teach and support students learning of a particular mathematical concept or behaviour. For example, we may wish to focus students’ attention on how they might develop better or more convincing mathematical arguments. In another lesson we might consider how to best develop conceptual understanding of averages as measures of location.

Whatever the focus, the teacher orchestrates whole-class discussion to construct a careful argument that seeks to ensure that students’ different thoughts are exposed, confronted, considered and resolved in ways that ensure as many students as possible leave the lesson having developed their understanding successfully. Central to this is a well-designed task that ensures that whole-class discussion can take place.

To illustrate, consider how a particular problem-solving lesson might play out. The diagram below shows a solid with constant cross-section. Students are asked to calculate its volume using one or more methods. This is a task that my colleague Professor Keiichi Nishimura used with his Teacher Research Group in Tokyo. To this point students will have learnt that the volume of a prism, such as a cuboid, is found by calculating base area x height . Importantly, all diagrams of prisms the students will have met to date will have been drawn carefully with the constant cross section of the prism positioned as base and often shaded.

As in all Japanese Problem Solving lessons, at the start of the lesson the task is introduced, and students are given 10-15 minutes to work on it, either on their own or possibly in pairs or groups.

An important part of Lesson Study in Japan is that the teachers think carefully about all of the possible ways in which students might go about solving the problem. This allows the teacher to identify the solutions they want to share with the whole class and the order in which they would like to do this. As the students work on the problem the teacher identifies which students’ work they will draw upon according to their plan, selecting those examples that will provide mathematical insight and concept development. At this point you may like to think about what you might expect students to do in this first phase of the lesson when working with this particular task: think about all of the different ways in which students might respond.

This next diagram shows the students’ methods that the teacher identified to share with the class in the class discussion phase of the lesson, where shared understanding is developed. At this stage, given that students are used to calculating the volume of a prism as (base area) x height, you may like to consider the different ways in which the students are ‘seeing’ the problem: what are they taking as the base? How have they split the problem up so as to find the volumes of different cuboids?

These questions were raised with students in a lesson focusing on how different students were thinking about the problem and how these different approaches all eventually lead to the same calculated value. An important issue the teacher drew attention to, after gathering these different expressions, was how each of these can be expressed as 44 x 8. This allowed the teacher to emphasise that in this case the volume can be found by multiplying the area of the constant cross-section, BFGLKC, considered as the ‘base’ by the height of the solid. This shows students a method that will work for more complex composite solids in the future.

Overall this lesson focused on what is effectively developing understanding of how we can calculate the volume of composite solids. It also provides insight into how the ‘maths sentences’ we write can provide a window on our thinking processes. This latter issue is something that students do not always pay attention to and is something that deserves more time and focus.

The common practice of sharing students’ work in this lesson format can be used to encourage students to think carefully about how they communicate their mathematical thinking clearly in their writing and diagrams in ways that reveal their understanding of mathematical structure. In Japan the whole practice is informed by carefully considered curriculum expertise in relation to concept development and the learning of maths.

As a final thought you might like to think about (1) how the dimensions of the L-shaped prism have been carefully chosen so that by judicious splitting into two cuboids and realignment of these a single cuboid can be achieved, and (2) how the teacher might work with their class to find the volume of the solid by finding the volume of a surrounding cuboid and subtracting the missing volume CDJK x KL.

The benefits achieved through teachers working together in groups are also seen in Singapore, where they work collaboratively in groups called PLCs: Professional Learning Communities. This is discussed in Professor Berinderjeet Kaur‘s blogpost here .

You can learn more about the use of lesson study to inform task design from our colleague in Japan, Professor Toshiakira Fujii in this article .

Share this:

The Japanese “5 Whys” Problem Solving Technique

by James Kirk

Are you aware of the problem solving technique called the “5 Whys”? It’s a technique originally developed decades ago in Japanese manufacturing plants, and is now used the world over as an aid to get quickly to the root of a problem. Simply put, you continue to ask the question “Why” until a root cause is found. Here are a few examples of how to use the technique.

My computer will not get on the internet. – PROBLEM

Why? 1 – My browser displays a “Page cannot be found” error.

Why? 2 – My computer says that it is disconnected from the network.

Why? 3 – There is no “link” light on my computer’s network card even with the cable plugged in.

Why? 4 – The network switch my computer’s network cable is attached to seems to be off.

Why? 5 – The switch’s power cord has become disconnected. (OFTEN ROOT CAUSE)

I am uncertain about our server backup situation. – PROBLEM

WHY? 1 – The few tapes we do have almost never make it offsite.

WHY? 2 – Our backup situation requires unnecessary human interaction.

WHY? 3 – Because we have an antiquated tape backup system.

WHY? 4 – We do not have veteran network analysts serving as our advocates in this area.

WHY? 5 – We are not using AVAREN as our IT department. (OFTEN ROOT CAUSE)

The technique will generally only find one root cause for any problem. In situations where more than one root cause is to blame additional repetitions or even additional techniques can be necessary. Nonetheless, if you find yourself with a problem and don’t know how to begin troubleshooting, this easy to remember technique can often yield quick results.

Publications in English

Please contact JUSE Press,Ltd. ( [email protected] ) if you have any questions or wish to purchase following books.

Publications

- About QC Circle

ISSN 2050-5337 - ISSUE 6 Find us in EBSCOhost Academic Search Ultimate Collection

- Issue 6: Creativity development

- Issue 5: Creative Aging in the USA

- Issue 4: Creativity in Japan

- Issue 3: Creativity research in Romania

- Issue 2: Creativity around the world

- Issue 1: Creativity exploded

- Book Reviews

- Editorial Team

- Submit material

- CCET Charity

- Compare plans

- Membership options

- Email newsletter

- Introduction to KJ-Ho - a Japanese problem solving approach

- font size decrease font size increase font size

The KJ Ho (Method) is a creative thinking and problem solving methodology, which was originally invented by Japanese cultural anthropologist, Professor Jiro Kawakita (1920-2009). It has gone through over half a century’s development and refinement as a result of applications to many kinds of complex and unique problems in Japan. This article is an up-to-date presentation of the current state of the KJ Ho by those who have contributed to its recent developments and improvements.

Written by Professor Toshio Nomura, Professor Susumu Kunifuji, Dr Mikio Naganobu, Dr Susumu Maruyama & Professor Motoki Miura.

This research was in part supported by Nomi City.

The KJ Ho (Method) is a creative thinking and problem solving methodology, which was originally invented by Japanese cultural anthropologist, Professor Jiro Kawakita (1920-2009). It has gone through over half a century’s development and refinement as a result of applications to many kinds of complex and unique problems in Japan. This article is an up-to-date presentation of the current state of the KJ Ho by those who have contributed to its recent developments and improvements.

It is not the strongest of the species that survives, nor the most intelligent, but the one most responsive to change. (Charles Darwin)

This article is the first presentation of the KJ Ho (Method) in English, including some detailed explanations and examples of basic steps and recent cases. The KJ Ho is the creative thinking and problem solving methodology that was originally invented by the late Professor Jiro Kawakita (1920-2009), a well-established cultural anthropologist in Japan; hence the use of his initials KJ (Figure 1 - Prof Jiro Kawakita).

In March 2011, Tohoku, Japan experienced unprecedented, natural and artificial disasters following an earthquake and tsunami, resulting in nuclear meltdowns at the Fukushima 1 nuclear power station. Since then, the majority of nuclear power stations in Japan have been shut down for thorough examinations. This has led to a comprehensive rethinking of electricity supply across the country with 30% less electricity available than before. The earthquake damaged a large number of manufacturing facilities in the Tohoku area, responsible for the production of various key manufacturing components. This has resulted in the suspension of some operations in automotive manufacturing plants globally for many months. A similar incident occurred after severe flooding hit Thailand in June 2011, affecting the global electronics industry.

The rise of emerging countries has been significantly changing the international industry landscape. This trend has dramatically changed the dynamics of global industries, which continue to grow increasingly more complex. It is clear that the world is far more connected and in flux than it was a couple of decades ago and incidents like those mentioned above can have massive global consequences. As Jiro Kawakita stated over 20 years ago, ‘the complexity of our world has far outstripped any ready-made theories or hypotheses, and a priori assumptions and wishful thinking are useless’ (Kawakita, 1991). We believe that the KJ Ho is a useful tool in dealing with a world growing increasingly complex, with its diverse and flexible approach to problem solving.

The KJ Ho has gone through over half a century’s development and refinement as the result of applications to many kinds of complex and unique problems in Japan. It has a fundamental capability of tolerating exceptional circumstances, rather than excluding them. As individuals who have contributed to the KJ Ho’s past and present developments and improvements, we feel that now is an appropriate time to present the current state of the KJ Ho, correctly and concisely.

It is important to note that in this English version of the KJ Ho article, the traditional translation of ‘Ho’ to ‘Method’ has not been used, as we felt that it lacked some of the principles and mental aspects associated with ‘KJ Ho’. For this reason, we decided to maintain the original Japanese KJ 法 (KJ Ho). We hope that this naming will settle down as de facto, as many other Japanese words have, such as Judo, Kaizen, Kansei, Karaoke, Sushi, Zen, etc.

This article is based on a seminar at the Anthropology Department of University College London and a workshop at the Creativity Centre Educational Trust (CCET) in Leeds in November 2011.

Your subscription helps support the non-profit Creativity & Human Development eJournal project, run by UK charity The Creativity Centre Educational Trust.

- creative problem solving

Related items

- Creative Problem Solving Institute - CPSI - 2022

- A Review of Formal Creative Problem Solving Programmes

- Creativity in Japan Today

- Beliefs and Attitudes About Creativity Among Japanese University Students

Member login

- Create an account

- Forgot your username?

- Forgot your password?

News by date

I can't understand why people are frightened of new ideas. i'm frightened of the old ones..

Login here if you have an account or click below to create an account.

COMMENTS

Abstract. In Japan, by far the most popular creative problem-solving methodology using creative thinking is the KJ Ho method. This method puts unstructured information on a subject matter of interest into order through alternating divergent and convergent thinking steps. In this paper, we explain basic procedures associated with the KJ Ho and ...

Abstract. The KJ Ho (Method) is a creative thinking and problem solving methodology, which was originally invented by Japanese cultural anthropologist, Professor Jiro Kawakita (1920-2009). It has gone through over half a century's development and refinement as a result of applications to many kinds of complex and unique problems in Japan.

This approach is then optimized until the problem is solved. However, while this often ends up with one solution, it usually is far from the best solution possible. In Japan, a very different multidimensional problem-solving approach is common. Rather than just use any solution that solves the problem, they aim for the best solution they can find.

Fig. 2Basic steps of the KJ Ho method [8] A Japanese Problem-Solving Approach: The KJ Ho Method 167. (a) Cause and effect: One is a predecessor or a cause of another. (b) Contradiction: Objects are conflicting to each other. (c) Interdependence: Objects are dependent on each other. (d) Correlation: Both objects relate to one another in some way.

Non-Japanese who work with them, either as employees or suppliers, need to be familiar with one of the key techniques they use for pursuing perfection, "saihatsu boshi.". Translated literally, this means "prevention of reoccurrence.". But the simplicity of this phrase belies the deep significance it has for many Japanese.

While Kaizen is the most widely used Japanese continuous improvement concept, some other quality management and problem-solving ideas have made their way from Japan to the US. Muri: One of the first things that plant managers engaging in improvement focus on is called Muri. Muri translates to "totally unreasonable."

The KJ Method is an approach to problem-solving and information sorting, developed by Japanese ethnologist Jiro Kawakita. This method puts unstructured information on a subject matter of interest ...

A Japanese problem solving approach: the KJ-Ho method . Susumu Kunifuji. Professor & Vice President, Japan Advanced Iinstitute for Science and Technology, Kanazawa, Japan. [email protected] . Abstract. In Japan, by far the most popular creative problem-solving methodology using creative thinking is the KJ Ho method. This method puts

Although Japanese structured problem solving has been influenced by U.S. research on problem solving, it is not the same as the pr oblem solving approach used in the U.S. In the U.S., problem solving is often viewed as an approach to develop problem-solving skills and strategies. As a result, U.S. mathematics lessons employing the problem

Using Japanese productivity methods, individuals and organizations can improve productivity and efficiency in several ways. Some more of the approaches include: Lean manufacturing: It was developed in Japan in the 1950s as an approach to production that emphasizes continuous improvement, waste reduction, and customer focus. The process involves ...

As in all Japanese Problem Solving lessons, at the start of the lesson the task is introduced, and students are given 10-15 minutes to work on it, either on their own or possibly in pairs or groups. An important part of Lesson Study in Japan is that the teachers think carefully about all of the possible ways in which students might go about ...

called "teaching though problem solving." Since Japanese structured problem solving uses problem solving as a process for learning mathematical content, it could be considered a type of teaching through problem solving. Looking at problem solving as a process for students to learn mathematics is not unique to Japanese mathematics education.

Although there are different approaches to addressing problem solving in mathematics lessons, mathematics education experts agree that problem solving should be integral to the curriculum (Cai and ...

The Japanese "5 Whys" Problem Solving Technique. by James Kirk Are you aware of the problem solving technique called the "5 Whys"? It's a technique originally developed decades ago in Japanese manufacturing plants, and is now used the world over as an aid to get quickly to the root of a problem. Simply put, you continue to ask the ...

Teaching Mathematics Through Problem-Solving offers an innovative new approach to teaching mathematics written by a leading expert in Japanese mathematics education, suitable for pre-service and in-service primary and secondary math educators. This engaging book offers an in-depth introduction to teaching mathematics through problem-solving ...

Basic procedures associated with the KJ Ho method are explained and some of its most specific applications are pointed out. In Japan, by far the most popular creative problem-solving methodology using creative thinking is the KJ Ho method. This method puts unstructured information on a subject matter of interest into order through alternating divergent and convergent thinking steps.

Abstract. It is known from many international studies that Japanese students do well in mathematics. This paper describes a typical lesson from a Japanese fifth-grade classroom, and discusses the ...

homeland before Japanese business imported his ideas and made them work in Japan. Deming encouraged the Japanese to adopt a systematic approach to problem solving. He also encouraged senior managers to become actively involved in their company's quality improvement programs. His greatest contribution was the concept that the consumers are

Japanese companies also face difficulties in eras of change. There is a need for paradigm shifts in management style. This paper will look at four case studies of major global companies and analyze the concept of the hybrid approach. It looks at how western and Japanese ways of thinking and methods can be combined to create a new model.

The QC Problem Solving-Approach Solving Workplace Problems the Japanese Way: Author: Katsuya Hosotani: Price: JPY 3,000: Contents: Chapter 1 The Importance of Problem Solving Chapter 2 What Is the QC Problem-Solving Approach? Chapter 3 The QC Viewpoint‐Vital for QC-Type Problem Solving ...

Networking Issue 6-06.qxp. Networking. The Problem with Traditional Problem-Solving. W hen you're facing a prob-lem, do you try to "fix" it with a tried-and-true process? Perhaps you gather data about what is broken or missing, analyze and chart your findings, try to logically determine what is wrong or the root cause of the problem ...

Abstract. The KJ Ho (Method) is a creative thinking and problem solving methodology, which was originally invented by Japanese cultural anthropologist, Professor Jiro Kawakita (1920-2009). It has gone through over half a century's development and refinement as a result of applications to many kinds of complex and unique problems in Japan.

Study with Quizlet and memorize flashcards containing terms like Which of the following is not a basic element in a problem-solving approach?, Problem-solving policing requires police to:, A departmental-wide strategy aimed at solving persistent community problems is called: and more.