AI ASSISTANTS

Upmetrics AI Your go-to AI-powered business assistant

AI Writing Assist Write, translate, and refine your text with AI

AI Financial Assist Automated forecasts and AI recommendations

TOP FEATURES

AI Business Plan Generator Create business plans faster with AI

Financial Forecasting Make accurate financial forecasts faster

INTEGRATIONS

Quickbooks Sync and compare with your quickbooks data

Strategic Planning Develop actionable strategic plans on-the-go

AI Pitch Deck Generator Use AI to generate your investor deck

Xero Sync and compare with your Xero data

See how it works →

AI-powered business planning software

Very useful business plan software connected to AI. Saved a lot of time, money and energy. Their team is highly skilled and always here to help.

- Julien López

BY USE CASE

Secure Funding, Loans, Grants Create plans that get you funded

Starting & Launching a Business Plan your business for launch and success

Validate Your Business Idea Discover the potential of your business idea

Business Consultant & Advisors Plan with your team members and clients

Incubators & Accelerators Empowering startups for growth and investor readiness

Business Schools & Educators Simplify business plan education for students

Students & Learners Your e-tutor for business planning

- Sample Plans

WHY UPMETRICS?

Reviews See why customers love Upmetrics

Customer Success Stories Read our customer success stories

Blogs Latest business planning tips and strategies

Strategic Planning Templates Ready-to-use strategic plan templates

Business Plan Course A step-by-step business planning course

Ebooks & Guides A free resource hub on business planning

Business Tools Free business tools to help you grow

How to Write Competitive Analysis in a Business Plan (w/ Examples)

Free Competitive Analysis Kit

- Vinay Kevadia

- January 9, 2024

14 Min Read

Every business wants to outperform its competitors, but do you know the right approach to gather information and analyze your competitors?

That’s where competitive analysis steps in. It’s the tool that helps you know your competition’s pricing strategies, strengths, product details, marketing strategies, target audience, and more.

If you want to know more about competitor analysis, this guide is all you need. It spills all the details on how to conduct and write a competitor analysis in a business plan, with examples.

Let’s get started and first understand the meaning of competitive analysis.

What is Competitive Analysis?

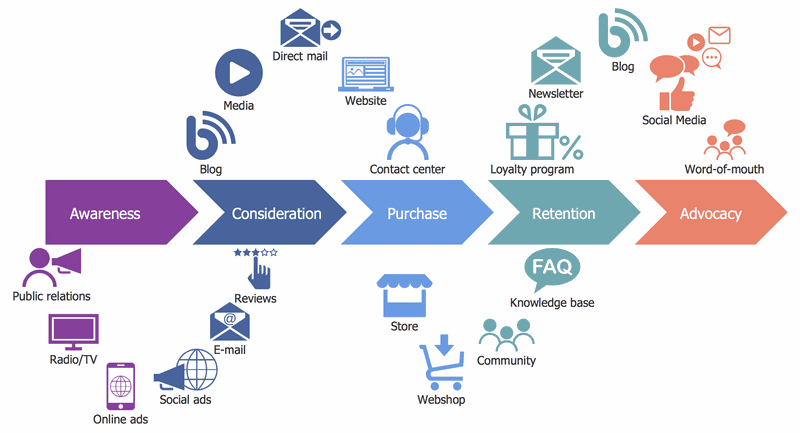

A competitive analysis involves collecting information about what other businesses in your industry are doing with their products, sales, and marketing.

Businesses use this data to find out what they are good at, where they can do better, and what opportunities they might have. It is like checking out the competition to see how and where you can improve.

This kind of analysis helps you get a clear picture of the market, allowing you to make smart decisions to make your business stand out and do well in the industry.

Competitive analysis is a section of utmost value for your business plan. The analysis in this section will form the basis upon which you will frame your marketing, sales, and product-related strategies. So make sure it’s thorough, insightful, and in line with your strategic objectives.

Let’s now understand how you can conduct a competitive analysis for your own business and leverage all its varied benefits.

How to Conduct a Competitive Analysis

Let’s break down the process of conducting a competitive analysis for your business plan in these easy-to-follow steps.

It will help you prepare a solid competitor analysis section in your business plan that actually highlights your strengths and opens room for better discussions (and funding).

Let’s begin.

1. Identify Your Direct and Indirect Competitors

First things first — identify all your business competitors and list them down. You can have a final, detailed list later, but right now an elementary list that mentions your primary competitors (the ones you know and are actively competing with) can suffice.

As you conduct more research, you can keep adding to it.

Explore your competitors using Google, social media platforms, or local markets. Then differentiate them into direct or indirect competitors.

Direct competitors

Businesses offering the same products or services, and targeting a similar target market are your direct competitors.

These competitors operate in the same industry and are often competing for the same market share.

Indirect competitors

On the other hand, indirect competitors are businesses that offer different products or services but cater to the same target customers as yours.

While they may not offer identical solutions, they compete for the same customer budget or attention. Indirect competitors can pose a threat by providing alternatives that customers might consider instead of your offerings.

2. Study the Overall Market

Now that you know your business competitors, deep dive into market research. Market research should involve a combination of both primary and secondary research methods.

Primary research

Primary research involves collecting market information directly from the source or subjects. Some examples of primary market research methods include:

- Purchasing competitors’ products or services

- Conducting interviews with their customers

- Administering online surveys to gather customer insights

Secondary research

Secondary research involves utilizing pre-existing gathered information from some relevant sources. Some of its examples include:

- Scrutinizing competitors’ websites

- Assessing the current economic landscape

- Referring to online market databases of the competitors.

Have a good understanding of the market at this point to write your market analysis section effectively.

3. Prepare a Competitive Framework

Now that you have a thorough understanding of your competitors’ market, it is time to create a competitive framework that enables comparison between two businesses.

Factors like market share, product offering, pricing, distribution channel, target markets, marketing strategies, and customer service offer essential metrics and information to chart your competitive framework.

These factors will form the basis of comparison for your competitive analysis. Depending on the type of your business, choose the factors that are relevant to you.

4. Take Note of Your Competitor’s Strategies

Now that you have an established framework, use that as a base to analyze your competitor’s strategies. Such analysis will help you understand what the customers like and dislike about your competitors.

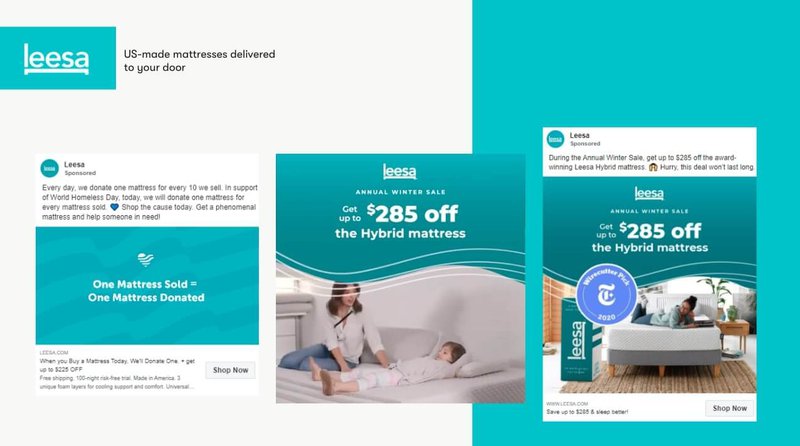

Start by analyzing the marketing strategies, sales and marketing channels, promotional activities, and branding strategies of your competitors. Understand how they position themselves in the market and what USPs they emphasize.

Evaluate, analyze their pricing strategies and keep an eye on their distribution channel to understand your competitor’s business model in detail.

This information allows you to make informed decisions about your strategies, helping you identify opportunities for differentiation and improvement.

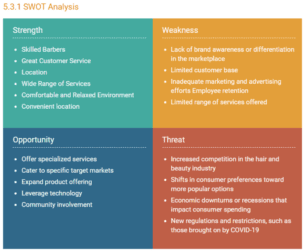

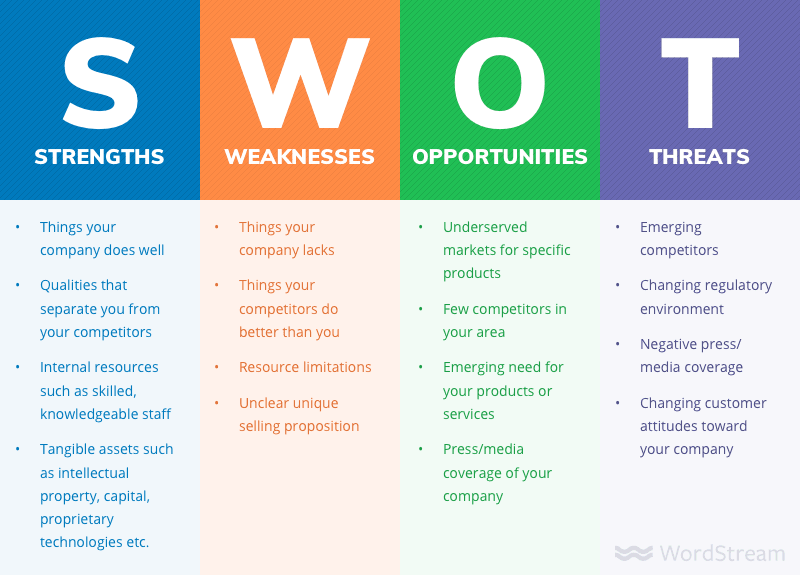

5. Perform a SWOT Analysis of Your Competitors

A SWOT analysis is a method of analyzing the strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats of your business in the competitive marketplace.

While strengths and weaknesses focus on internal aspects of your company, opportunities and threats examine the external factors related to the industry and market.

It’s an important tool that will help determine the company’s competitive edge quite efficiently.

It includes the positive features of your internal business operations. For example, a strong brand, skilled workforce, innovative products/services, or a loyal customer base.

It includes all the hindrances of your internal business operations. For example, limited resources, outdated technology, weak brand recognition, or inefficient processes.

Opportunities

It outlines several opportunities that will come your way in the near or far future. Opportunities can arise as the industry or market trend changes or by leveraging the weaknesses of your competitors.

For example, details about emerging markets, technological advancements, changing consumer trends, profitable partnerships in the future, etc.

Threats define any external factor that poses a challenge or any risk for your business in this section. For example, intense competition, economic downturns, regulatory changes, or any advanced technology disruption.

This section will form the basis for your business strategies and product offerings. So make sure it’s detailed and offers the right representation of your business.

And that is all you need to create a comprehensive competitive analysis for your business plan.

Want to Perform Competitive Analysis for your Business?

Discover your competition’s secrets effortlessly with our user-friendly and Free Competitor Analysis Generator!

How to Write Competitive Analysis in a Business Plan

The section on competitor analysis is the most crucial part of your business plan. Making this section informative and engaging gets easier when you have all the essential data to form this section.

Now, let’s learn an effective way of writing your competitive analysis.

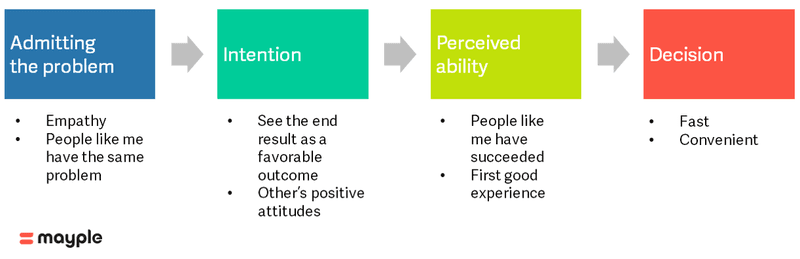

1. Determine who your readers are

Know your audience first, because that will change the whole context of your competitor analysis business plan.

The competitive analysis section will vary depending on the intended audience is the team or investors.

Consider the following things about your audience before you start writing this section:

Internal competitor plan (employees or partners)

Objective: The internal competitor plan is to provide your team with an understanding of the competitive landscape.

Focus: The focus should be on the comparison of the strengths and weaknesses of competitors to boost strategic discussions within your team.

Use: It is to leverage the above information to develop strategies that highlight your strengths and address your weaknesses.

Competitor plan for funding (bank or investors)

Objective: Here, the objective is to reassure the potential and viability of your business to investors or lenders.

Focus: This section should focus on awareness and deep understanding of the competitive landscape to persuade the readers about the future of your business.

Use: It is to showcase your market position and the opportunities that are on the way to your business.

This differentiation is solely to ensure that the competitive analysis serves its purpose effectively based on the specific needs and expectations of the respective audience.

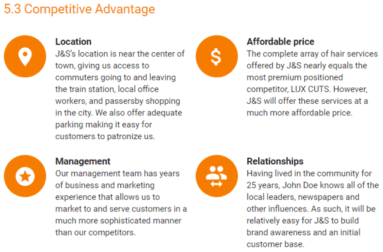

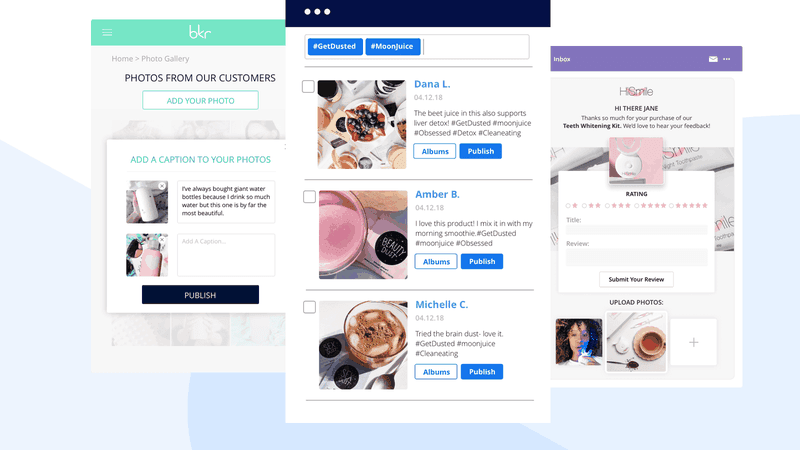

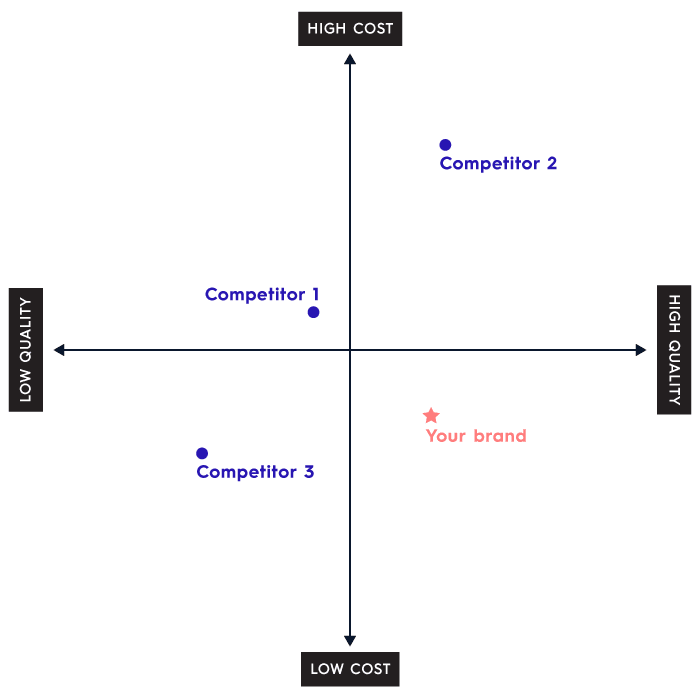

2. Describe and Visualise Competitive Advantage

Remember how we determined our competitive advantage at the time of research. It is now time to present that advantage in your competitive analysis.

Highlight your edge over other market players in terms of innovation, product quality, features, pricing, or marketing strategy. Understanding your products’ competitive advantage will also help you write the products and services section effectively.

However, don’t limit the edge to your service and market segment. Highlight every area where you excel even if it is better customer service or enhanced brand reputation.

Now, you can explain your analysis through textual blocks. However, a more effective method would be using a positioning map or competitive matrix to offer a visual representation of your company’s competitive advantage.

3. Explain your strategies

Your competitor analysis section should not only highlight the opportunities or threats of your business. It should also mention the strategies you will implement to overcome those threats or capitalize on the opportunities.

Such strategies may include crafting top-notch quality for your products or services, exploring the unexplored market segment, or having creative marketing strategies.

Elaborate on these strategies later in their respective business plan sections.

4. Know the pricing strategy

To understand the pricing strategy of your competitors, there are various aspects you need to have information about. It involves knowing their pricing model, evaluating their price points, and considering the additional costs, if any.

One way to understand this in a better way is to compare features and value offered at different price points and identify the gaps in competitors’ offerings.

Once you know the pricing structure of your competitors, compare it with yours and get to know the competitive advantage of your business from a pricing point of view.

Let us now get a more practical insight by checking an example of competitive analysis.

Competitive Analysis Example in a Business Plan

Here’s a business plan example highlighting the barber shop’s competitive analysis.

1. List of competitors

Direct & indirect competitors.

The following retailers are located within a 5-mile radius of J&S, thus providing either direct or indirect competition for customers:

Joe’s Beauty Salon

Joe’s Beauty Salon is the town’s most popular beauty salon and has been in business for 32 years. Joe’s offers a wide array of services that you would expect from a beauty salon.

Besides offering haircuts, Joe’s also offers nail services such as manicures and pedicures. In fact, over 60% of Joe’s revenue comes from services targeted at women outside of hair services. In addition, Joe’s does not offer its customers premium salon products.

For example, they only offer 2 types of regular hair gels and 4 types of shampoos. This puts Joe’s in direct competition with the local pharmacy and grocery stores that also carry these mainstream products. J&S, on the other hand, offers numerous options for exclusive products that are not yet available in West Palm Beach, Florida.

LUX CUTS has been in business for 5 years. LUX CUTS offers an extremely high-end hair service, with introductory prices of $120 per haircut.

However, LUX CUTS will primarily be targeting a different customer segment from J&S, focusing on households with an income in the top 10% of the city.

Furthermore, J&S offers many of the services and products that LUX CUTS offers, but at a fraction of the price, such as:

- Hairstyle suggestions & hair care consultation

- Hair extensions & coloring

- Premium hair products from industry leaders

Freddie’s Fast Hair Salon

Freddie’s Fast Hair Salon is located four stores down the road from J&S. Freddy’s has been in business for the past 3 years and enjoys great success, primarily due to its prime location.

Freddy’s business offers inexpensive haircuts and focuses on volume over quality. It also has a large customer base comprised of children between the ages of 5 to 13.

J&S has several advantages over Freddy’s Fast Hair Salon including:

- An entertainment-focused waiting room, with TVs and board games to make the wait for service more pleasurable. Especially great for parents who bring their children.

- A focus on service quality rather than speed alone to ensure repeat visits. J&S will spend on average 20 more minutes with its clients than Freddy’s.

While we expect that Freddy’s Fast Hair Salon will continue to thrive based on its location and customer relationships, we expect that more and more customers will frequent J&S based on the high-quality service it provides.

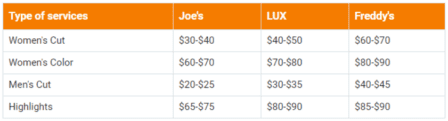

2. Competitive Pricing

John and Sons Barbing Salon will work towards ensuring that all our services are offered at highly competitive prices compared to what is obtainable in The United States of America.

We know the importance of gaining entrance into the market by lowering our pricing to attract all and sundry that is why we have consulted with experts and they have given us the best insights on how to do this and effectively gain more clients soon.

Our pricing system is going to be based on what is obtainable in the industry, we don’t intend to charge more (except for premium and customized services) and we don’t intend to charge less than our competitors are offering in West Palm Beach – Florida.

3. Our pricing

- Payment by cash

- Payment via Point of Sale (POS) Machine

- Payment via online bank transfer (online payment portal)

- Payment via Mobile money

- Check (only from loyal customers)

Given the above, we have chosen banking platforms that will help us achieve our payment plans without any itches.

4. Competitive advantage

5. SWOT analysis

Why is a Competitive Environment helpful?

Somewhere we all think, “What if we had no competition?” “What if we were the monopoly?” It would be great, right? Well, this is not the reality, and have to accept the competition sooner or later.

However, competition is healthy for businesses to thrive and survive, let’s see how:

1. Competition validates your idea

When people are developing similar products like you, it is a sign that you are on the right path. Having healthy competition proves that your idea is valid and there is a potential target market for your product and service offerings.

2. Innovation and Efficiency

Businesses competing with each other are motivated to innovate consistently, thereby, increasing their scope and market of product offerings. Moreover, when you are operating in a cutthroat environment, you simply cannot afford to be inefficient.

Be it in terms of costs, production, pricing, or marketing—you will ensure efficiency in all aspects to attract more business.

3. Market Responsiveness

Companies in a competitive environment tend to stay relevant and longer in business since they are adaptive to the changing environment. In the absence of competition, you would start getting redundant which will throw you out of the market, sooner or later.

4. Eases Consumer Education

Since your target market is already aware of the problem and existing market solutions, it would be much easier to introduce your business to them. Rather than focusing on educating, you would be more focused on branding and positioning your brand as an ideal customer solution.

Being the first one in the market is exciting. However, having healthy competition has these proven advantages which are hard to ignore.

A way forward

Whether you are starting a new business or have an already established unit, having a practical and realistic understanding of your competitive landscape is essential to developing efficient business strategies.

While getting to know your competition is essential, don’t get too hung up in the research. Research your competitors to improve your business plan and strategies, not to copy their ideas.

Create your unique strategies, offer the best possible services, and add value to your offerings—that will make you stand out.

While it’s a long, tough road, a comprehensive business plan can be your guide. Using modern business planning software is probably the easiest way to draft your plan.

Use Upmetrics. Simply enter your business details, answer the strategic questions, and see your business plan come together in front of your eyes.

Build your Business Plan Faster

with step-by-step Guidance & AI Assistance.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is swot analysis a competitive analysis.

SWOT analysis is just a component of a competitive analysis and not the whole competitive analysis. It helps you identify the strengths and weaknesses of your business and determine the emerging opportunities and threats faced by the external environment.

Competitive analysis in reality is a broad spectrum topic wherein you identify your competitors, analyze them on different metrics, and identify your competitive advantage to form competitive business strategies.

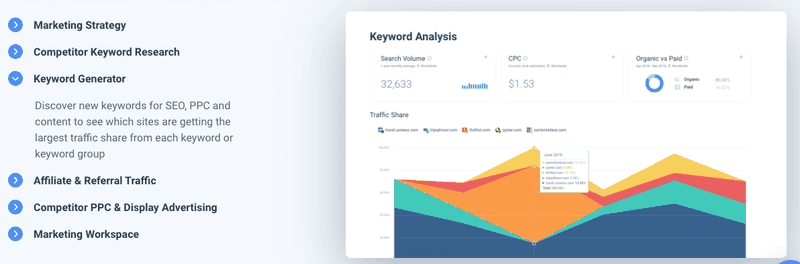

What tools can i use for competitor analysis?

For a thorough competitor analysis, you will require a range of tools that can help in collecting, analyzing, and presenting data. While SEMrush, Google Alerts, Google Trends, and Ahrefs can help in collecting adequate competitor data, Business planning tools like Upmetrics can help in writing the competitors section of your business plan quite efficiently.

What are the 5 parts of a competitive analysis?

The main five components to keep in mind while having a competitor analysis are:

- Identifying the competitors

- Analyzing competitor’s strengths and weaknesses

- Assessing market share and trends

- Examining competitors’ strategies and market positioning

- Performing SWOT analysis

What is the difference between market analysis and competitive analysis?

Market analysis involves a comprehensive examination of the overall market dynamics, industry trends, and factors influencing a business’s operating environment.

On the other hand, competitive analysis narrows the focus to specific competitors within the market, delving into their strategies, strengths, weaknesses, and market positioning.

About the Author

Vinay Kevadiya

Vinay Kevadiya is the founder and CEO of Upmetrics, the #1 business planning software. His ultimate goal with Upmetrics is to revolutionize how entrepreneurs create, manage, and execute their business plans. He enjoys sharing his insights on business planning and other relevant topics through his articles and blog posts. Read more

Related Articles

How to Write a Customer Analysis Section for Your Business Plan

What is SWOT Analysis & How to Conduct it

How to Conduct a PESTLE Analysis Explained with Example

Reach your goals with accurate planning.

No Risk – Cancel at Any Time – 15 Day Money Back Guarantee

How to Write a Competitive Analysis for Your Business Plan

11 min. read

Updated January 3, 2024

Do you know who your competitors are? If you do, have you taken the time to conduct a thorough competitor analysis?

Knowing your competitors, how they operate, and the necessary benchmarks you need to hit are crucial to positioning your business for success. Investors will also want to see an analysis of the competition in your business plan.

In this guide, we’ll explore the significance of competitive analysis and guide you through the essential steps to conduct and write your own.

You’ll learn how to identify and evaluate competitors to better understand the opportunities and threats to your business. And you’ll be given a four-step process to describe and visualize how your business fits within the competitive landscape.

- What is a competitive analysis?

A competitive analysis is the process of gathering information about your competitors and using it to identify their strengths and weaknesses. This information can then be used to develop strategies to improve your own business and gain a competitive advantage.

- How to conduct a competitive analysis

Before you start writing about the competition, you need to conduct your analysis. Here are the steps you need to take:

1. Identify your competitors

The first step in conducting a comprehensive competitive analysis is to identify your competitors.

Start by creating a list of both direct and indirect competitors within your industry or market segment. Direct competitors offer similar products or services, while indirect competitors solve the same problems your company does, but with different products or services.

Keep in mind that this list may change over time. It’s crucial to revisit it regularly to keep track of any new entrants or changes to your current competitors. For instance, a new competitor may enter the market, or an existing competitor may change their product offerings.

2. Analyze the market

Once you’ve identified your competitors, you need to study the overall market.

This includes the market size , growth rate, trends, and customer preferences. Be sure that you understand the key drivers of demand, demographic and psychographic profiles of your target audience , and any potential market gaps or opportunities.

Conducting a market analysis can require a significant amount of research and data collection. Luckily, if you’re writing a business plan you’ll follow this process to complete the market analysis section . So, doing this research has value for multiple parts of your plan.

Brought to you by

Create a professional business plan

Using ai and step-by-step instructions.

Secure funding

Validate ideas

Build a strategy

3. Create a competitive framework

You’ll need to establish criteria for comparing your business with competitors. You want the metrics and information you choose to provide answers to specific questions. (“Do we have the same customers?” “What features are offered?” “How many customers are being served?”)

Here are some common factors to consider including:

- Market share

- Product/service offerings or features

- Distribution channels

- Target markets

- Marketing strategies

- Customer service

4. Research your competitors

You can now begin gathering information about your competitors. Because you spent the time to explore the market and set up a comparison framework—your research will be far more focused and easier to complete.

There’s no perfect research process, so start by exploring sources such as competitor websites, social media, customer reviews, industry reports, press releases, and public financial statements. You may also want to conduct primary research by interviewing customers, suppliers, or industry experts.

You can check out our full guide on conducting market research for more specific steps.

5. Assess their strengths and weaknesses

Evaluate each competitor based on the criteria you’ve established in the competitive framework. Identify their key strengths (competitive advantages) and weaknesses (areas where they underperform).

6. Identify opportunities and threats

Based on the strengths and weaknesses of your competitors, identify opportunities (areas where you can outperform them) and threats (areas where they may outperform you) for your business.

You can check out our full guide to conducting a SWOT analysis for more specific questions that you should ask as part of each step.

- How to write your competitive analysis

Once you’ve done your research, it’s time to present your findings in your business plan. Here are the steps you need to take:

1. Determine who your audience is

Who you are writing a business plan for (investors, partners, employees, etc.) may require you to format your competitive analysis differently.

For an internal business plan you’ll use with your team, the competition section should help them better understand the competition. You and your team will use it to look at comparative strengths and weaknesses to help you develop strategies to gain a competitive advantage.

For fundraising, your plan will be shared with potential investors or as part of a bank loan. In this case, you’re describing the competition to reassure your target reader. You are showing awareness and a firm understanding of the competition, and are positioned to take advantage of opportunities while avoiding the pitfalls.

2. Describe your competitive position

You need to know how your business stacks up, based on the values it offers to your chosen target market. To run this comparison, you’ll be using the same criteria from the competitive framework you completed earlier. You need to identify your competitive advantages and weaknesses, and any areas where you can improve.

The goal is positioning (setting your business up against the background of other offerings), and making that position clear to the target market. Here are a few questions to ask yourself in order to define your competitive position:

- How are you going to take advantage of your distinctive differences, in your customers’ eyes?

- What are you doing better?

- How do you work toward strengths and away from weaknesses?

- What do you want the world to think and say about you and how you compare to others?

3. Visualize your competitive position

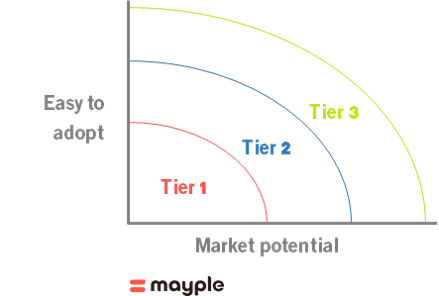

There are a few different ways to present your competitive framework in your business plan. The first is a “positioning map” and the second is a “competitive matrix”. Depending on your needs, you can use one or both of these to communicate the information that you gathered during your competitive analysis:

Positioning map

The positioning map plots two product or business benefits across a horizontal and vertical axis. The furthest points of each represent opposite extremes (Hot and cold for example) that intersect in the middle. With this simple chart, you can drop your own business and the competition into the zone that best represents the combination of both factors.

I often refer to marketing expert Philip Kohler’s simple strategic positioning map of breakfast, shown here. You can easily draw your own map with any two factors of competition to see how a market stacks up.

It’s quite common to see the price on one axis and some important qualitative factor on the other, with the assumption that there should be a rough relationship between price and quality.

Competitive matrix

It’s pretty common for most business plans to also include a competitive matrix. It shows how different competitors stack up according to the factors identified in your competitive framework.

How do you stack up against the others? Here’s what a typical competitive matrix looks like:

For the record, I’ve seen dozens of competitive matrices in plans and pitches. I’ve never seen a single one that didn’t show that this company does more of what the market wants than all others. So maybe that tells you something about credibility and how to increase it. Still, the ones I see are all in the context of seeking investment, so maybe that’s the nature of the game.

4. Explain your strategies for gaining a competitive edge

Your business plan should also explain the strategies your business will use to capitalize on the opportunities you’ve identified while mitigating any threats from competition. This may involve improving your product/service offerings, targeting underserved market segments, offering more attractive price points, focusing on better customer service, or developing innovative marketing strategies.

While you should cover these strategies in the competition section, this information should be expanded on further in other areas of your business plan.

For example, based on your competitive analysis you show that most competitors have the same feature set. As part of your strategy, you see a few obvious ways to better serve your target market with additional product features. This information should be referenced within your products and services section to back up your problem and solution statement.

- Why competition is a good thing

Business owners often wish that they had no competition. They think that with no competition, the entire market for their product or service will be theirs. That is simply not the case—especially for new startups that have truly innovative products and services. Here’s why:

Competition validates your idea

You know you have a good idea when other people are coming up with similar products or services. Competition validates the market and the fact that there are most likely customers for your new product. This also means that the costs of marketing and educating your market go down (see my next point).

Competition helps educate your target market

Being first-to-market can be a huge advantage. It also means that you will have to spend way more than the next player to educate customers about your new widget, your new solution to a problem, and your new approach to services.

This is especially true for businesses that are extremely innovative. These first-to-market businesses will be facing customers that didn’t know that there was a solution to their problem . These potential customers might not even know that they have a problem that can be solved in a better way.

If you’re a first-to-market company, you will have an uphill battle to educate consumers—an often expensive and time-consuming process. The 2nd-to-market will enjoy all the benefits of an educated marketplace without the large marketing expense.

Competition pushes you

Businesses that have little or no competition become stagnant. Customers have few alternatives to choose from, so there is no incentive to innovate. Constant competition ensures that your marketplace continues to evolve and that your product offering continues to evolve with it.

Competition forces focus & differentiation

Without competition, it’s easy to lose focus on your core business and your core customers and start expanding into areas that don’t serve your best customers. Competition forces you and your business to figure out how to be different than your competition while focusing on your customers. In the long term, competition will help you build a better business.

- What if there is no competition?

One mistake many new businesses make is thinking that just because nobody else is doing exactly what they’re doing, their business is a sure thing. If you’re struggling to find competitors, ask yourself these questions.

Is there a good reason why no one else is doing it?

The smart thing to do is ask yourself, “Why isn’t anyone else doing it?”

It’s possible that nobody’s selling cod-liver frozen yogurt in your area because there’s simply no market for it. Ask around, talk to people, and do your market research. If you determine that you’ve got customers out there, you’re in good shape.

But that still doesn’t mean there’s no competition.

How are customers getting their needs met?

There may not be another cod-liver frozen yogurt shop within 500 miles. But maybe an online distributor sells cod-liver oil to do-it-yourselfers who make their own fro-yo at home. Or maybe your potential customers are eating frozen salmon pops right now.

Are there any businesses that are indirect competitors?

Don’t think of competition as only other businesses that do exactly what you do. Think about what currently exists on the market that your product would displace.

It’s the difference between direct competition and indirect competition. When Henry Ford started successfully mass-producing automobiles in the U.S., he didn’t have other automakers to compete with. His competition was horse-and-buggy makers, bicycles, and railroads.

Do a competitive analysis, but don’t let it derail your planning

While it’s important that you know the competition, don’t get too caught up in the research.

If all you do is track your competition and do endless competitive analyses, you won’t be able to come up with original ideas. You will end up looking and acting just like your competition. Instead, make a habit of NOT visiting your competition’s website, NOT going into their store, and NOT calling their sales office.

Focus instead on how you can provide the best service possible and spend your time talking to your customers. Figure out how you can better serve the next person that walks in the door so that they become a lifetime customer, a reference, or a referral source.

If you focus too much on the competition, you will become a copycat. When that happens, it won’t matter to a customer if they walk into your store or the competition’s because you will both be the same.

Tim Berry is the founder and chairman of Palo Alto Software , a co-founder of Borland International, and a recognized expert in business planning. He has an MBA from Stanford and degrees with honors from the University of Oregon and the University of Notre Dame. Today, Tim dedicates most of his time to blogging, teaching and evangelizing for business planning.

Table of Contents

- Don't let competition derail planning

Related Articles

10 Min. Read

How to Write the Company Overview for a Business Plan

How to Set and Use Milestones in Your Business Plan

6 Min. Read

How to Write Your Business Plan Cover Page + Template

3 Min. Read

What to Include in Your Business Plan Appendix

The Bplans Newsletter

The Bplans Weekly

Subscribe now for weekly advice and free downloadable resources to help start and grow your business.

We care about your privacy. See our privacy policy .

The quickest way to turn a business idea into a business plan

Fill-in-the-blanks and automatic financials make it easy.

No thanks, I prefer writing 40-page documents.

Discover the world’s #1 plan building software

Plan Projections

ideas to numbers .. simple financial projections

Home > Business Plan > Competition in a Business Plan

Competition in a Business Plan

… there is competition in the target market …

Who is the Competition?

By carrying out a competitor analysis a business will be able to identify its own strengths and weaknesses, and produce its own strategy. For example a review of competitor products and prices will enable a business to set a realistic market price for its own products. The competition section of the business plan aims to show who you are competing with, and why the benefits your product provides to customers are better then those of the competition; why customers will choose your product over your competitors.

- Who are our competitors?

- What are the competitors main products and services?

- What threats does the competitor pose to our business?

- What are the strengths and weaknesses of our competitors?

- What are the objectives in the market place of the competitors?

- What strategies are the competitors using?

- What is the competitors market share?

- What market segments do the competitors operate in?

- What do customers think of the competition?

- What does the trade think of the competitor?

- What makes their product good?

- Why do customers buy their product?

- What problems do customers have with the product?

- What is the competitors financial strength?

- What resources do the competition have available?

The focus is on how well the customer benefits and needs are satisfied compared to competitors, and not on how the features of the product compare. For example, key customer benefits might include affordability, can be purchased online, or ease of use, but not a technical feature list.

Competition Presentation in the Business Plan

The business plan competitor section can be presented in a number of formats including a competitor matrix, but an informative way of presenting is using Harvey balls . Harvey balls allow you to grade each customer benefit from zero to four, and to show a comparison of these benefits to your main competitor products. The competitors might be individual identified companies, or a generic competitor such as ‘fast food restaurants’.

In the example below, the key benefits of the product are compared against three main competitors. Each row represents a key benefit to the customer, the first column represents your business, and the remaining three columns each represent a chosen competitor.

The investor will want to understand that your product has the potential to take a major share of the chosen target market by being shown that it is sufficiently competitive for a number of key customer benefits.

This is part of the financial projections and Contents of a Business Plan Guide , a series of posts on what each section of a simple business plan should include. The next post in this series will deal with the competitive advantages the business has in the chosen target market.

About the Author

Chartered accountant Michael Brown is the founder and CEO of Plan Projections. He has worked as an accountant and consultant for more than 25 years and has built financial models for all types of industries. He has been the CFO or controller of both small and medium sized companies and has run small businesses of his own. He has been a manager and an auditor with Deloitte, a big 4 accountancy firm, and holds a degree from Loughborough University.

You May Also Like

Home Page | Blog | Managing | Marketing | Planning | Strategy | Sales | Service | Networking | Voice Marketing Inc.

- Privacy Policy

Competition in Business

Use change management tools to learn how to adapt quickly to competitive actions.

Competition in business is always a challenge. Understand, and use, the definition of strategic planning by using business and sales plan examples. And use change management tools to adapt to competitive actions.

Understanding your competition is important: whether you are starting a new business, operating an existing business, entering new markets, or launching new products and services.

Search This Site

Competition in business can be a major stumbling block to growth and success.

To develop a strong competitive strategy, it is necessary to conduct a competitive analysis.

One of the best methods of dealing with competitive activity is to learn how to adapt and change quickly.

Use change management tools to learn managing change techniques.

Managing Growth and Change

A definition of strategic planning includes an understand of markets, customers, competition, and your business capabilities. Once you have that understanding (through research), you need to build strategies to handle your competitors.

As a small business owner, you need to develop a comprehensive strategy to deal with your competition (for example, you might want to include a pricing strategy; or perhaps, an alternative competitive strategy to cutting price; or a value chain analysis to assess your competition, and so on) and to operate in highly competitive markets. Even if you are the market leader today, the threat of losing that position tomorrow, or into the future, is very real if you do not have a solid plan in place.

Review sales plan examples to see how, when, where, what and why businesses change their plans to deal with competitive activity.

Writing a marketing plan includes doing a competitive analysis section. You need to assess your competition in business and try to predict what your competition might do in the case that you add new services, lower your price, raise your price, move closer to their markets, hire some of their staff, and more.

To analyze your competition, you must find out as much as you can about them: (do this for the top 3 to 10 competitors; you can analyze fewer if they hold big market shares; or analyze up to 10 if the market is buying from many).

Competition in Business: Focus on Analysis

Create your competitive analysis: gather the following information:.

- Who are your competitors? Identify your Top 3 to 10 (representing up to 80% of market share). List them by company name, business owner, address, etc.

- Who are your indirect competitors that don't necessarily sell the same products or services but their sales can affect your sales (e.g. if you sell motorcycles, bicycles and cars can be your competition)?

- What share of the market does each competitor hold? Get as close as possible. Is their position stronger or weaker in the market this year, compared to last year, compared to 3 to 5 years ago?

- What do you believe to be their strengths, weaknesses, opportunities and threats (SWOT)? What marketing tactics can you use to minimize their strengths and opportunities and maximize their weaknesses and threats?

- What are they doing in the marketing mix side: how are they handling marketing mix product , price strategy building , marketing mix promotion, and place or distribution (the forgotten mix in the 4 Ps of Marketing )? How effective are they with this program (rank them)?

- Do they have a website?

- What's their advertising frequency? Can you estimate their advertising/promotions budget? How do they advertise: television, radio, newspaper, trade magazines, direct mail, point of purchase?

- If their price advertised; is it higher, lower or about the same?

- What are their product/service features, advantages, and benefits (their product positioning , product differentiation, or product life cycle)?

- Compare their marketing mix approach to yours. What are their strengths and weaknesses?

- What is unique about your product or service compared to theirs? What is unique about your business compared to theirs?

- What about your customer service: is it better, worse or the same as your competition?

- Do you share customers? Or are your customers 100% yours?

- For indirect or new competitors: what is their barrier to entry into your direct market?

- Is physical location important in your market? Who has the 'best' location?

- Is brand recognition important in your market? Who has the 'best' brand?

Sources of competitor information:

- Website (if they have one); internet searches to see if the name(s) comes up;

- Annual Report (if they are a public company) - compare profitability of their business (and other comparable business performance measures) to yours;

- Their promotion and advertising program; try to get copies;

- Shared customers;

- Your sales staff; often they know a lot about the competition in business that they face;

- Your suppliers; often they supply your competitors; if they don't they may more freely share information about them;

- Trade shows; you can pick up promotional material from their booth, ask others about them;

- Trade associations; you can meet them directly, or find out more about them;

- Trade magazines; check out the back issues for announcements or news on your competition;

- Other media; newspapers, magazines, books, television, radio;

- If they have a physical storefront open to the public, go in. (Yes, that makes many people squirm but you're not doing anything illegal.) Check out their displays, see how they handle customers, how does their physical space look (clean, tidy and well organized)?

Once you've completed a thorough competitive analysis for your marketing plan, keep it up-to-date .

Understanding your competition in business means reviewing your gathered data on your competitors try to determine what their business strategies and growth objectives are; do your competitive intelligence work regularly. Continually assess progress they might make, against your own business progress. Assess the size of the market and try to determine if it will support the competition - if not, someone will go out of business. Make sure that it's not you.

More-For-Small-Business Newsletter:

For more timely and regular monthly information on managing your small business, please subscribe here..

| to send you More Business Resources. |

Additional Reading:

Return from Competition in Business to Definition of Marketing.

Return to More for Small Business Home Page.

Subscribe to

More Business Resources E-zine

| to send you More Business Resources. |

Marketing and Life–Cycle

Marketing is a requirement for all businesses: without marketing strategies and tactics your business will struggle to survive.

Not all marketing activities are planned: you might be building your brand recognition through a social media campaign (that's marketing); you might be conducting market research to analyze your competitors and/or segment and target your potential market or to develop the most desirable features, advantages and benefits of your products or services (that's all marketing).

Marketing is pretty all–encompassing; and a challenge for many business owners. The additional challenge is recognizing that the different stages of your business life–cycle: start–up, mid–cycle, mature or late–in–life.

During start–up you need to develop your marketing strategies to grow sales; for example, you might want to use a market penetration pricing strategy to build sales quickly.

During mid–cycle, you need to grow your customer base (often through lead generation) and that need requires different marketing strategies, such as cold calling on prospective clients, email marketing, newsletter and blog sign ups and distribution (all to grow your list of prospects).

During the mature cycle, you need to build your marketing efforts around your brand; your competitive advantage can be in your reputation, history, and identity and on what differentiates your business from your competitors.

Marketing your products and services is not something that you do once (such as a marketing plan) and then never change or do again. You need to be continually researching and building your strategies and tactics to be ahead of the market, and ahead of your competition.

The market is constantly evolving; ever more rapidly with the impacts of globalization and technology. You need to invest resources into marketing to ensure that you build and sustain your business.

- Build Your Marketing

Administration

- Advertising

Outsource Your Marketing

If you need support in your marketing efforts, or if you'd like a review of your marketing plan, contact us for more information on our marketing services.

If marketing is not your core strength, or if you don't have enough staff to commit to developing your marketing efforts (and acting on the plan), outsourcing your marketing strategy and implementation will allow you to concentrate on developing your business.

Start with a marketing plan that includes the necessary research, strategy development and implementation action plan. We provide you with the plan tactics, budget, schedule and key performance measurements.

Execute the plan yourself or have us at Voice Marketing Inc. manage the execution for you.

Once the plan is implemented, we report on the actions we've taken, the performance of the tactics employed, and on the results.

You'll feel confident that your business marketing is being effectively managed and continually evolving.

We specialize in providing services to small business owners and understand that marketing efforts must be customized for each business' unique needs.

Contact

We are located in the Greater Vancouver area of British Columbia, Canada.

You can reach us through our contact page or request a quote for services here .

- What is Value Chain Analysis?

- Business plan outlines?

- Do you have resources for marketing planning?

- More Questions and Answers

Find the right network for you!

Managing Time | Money | Human Resources | Website Building | FAQs | Privacy Policy | Site Index | About Us | Contact Us | Request Quote

Copyright © 2002 - 2018 Voice Marketing Inc. All Rights Reserved.

Site Policies | Privacy Policy | Disclosure | Advertising

- Market Research

How to create a competitive business plan

- January 3, 2023

When starting up a business, there are various building blocks you need to have in place for a strong foundation. A profitable idea is one, as is procuring the necessary finances to get everything up and running. Another key element is a well-researched, competitive business plan.

For new entrepreneurs, it can be easy to overlook the importance of a business plan. It might seem like a time-consuming, redundant document, particularly if they feel their idea is foolproof and ready to go.

However, there are many reasons to put together a business plan.

Some will simply see it as a gateway to the funding they require from a bank or other financial institution. In reality, a quality business plan supplies an accurate roadmap, one that points you in the right direction across every stage of running and managing a new business.

One such stage is analyzing the competition .

A competitive business plan is a great educational platform for your entrepreneurial adventure. You can learn more about your competitors, the current market opportunity, where your business fits in, and much more. This guide will explain how to create a competitive business plan, including what areas to focus on and which tools are best for gathering and analyzing data.

What is a competitive business plan?

A competitive business plan is about learning the type of competition your prospective business will face. The other businesses that are vying for the same customers.

Never assume you are out there alone and focus on solely your own path, that is a sure way to fail. Every solid business has to deal with some form of competition. You may not experience this directly during your company’s formative months, but it will always be there, dictating everything from sales numbers to the employees you can attract.

By putting together a competitive business plan, you gain a full understanding of the rivals in your sector. These rivals can take on various forms. For example, a new Italian restaurant could see their main competitor being the long-established pizza joint down the road. An online retail business, however, may be up against multinational organizations, including the likes of Amazon.

The knowledge gained by analyzing the competition assists with constructing a marketing sales strategy . It makes it possible to define how your business will fit into your chosen industry, including available opportunities and how to gain a competitive advantage.

Dive deep enough, and you will also discover the products and services your customer base enjoys, those they avoid, and the types of features they desire in future releases.

Related: 5 Examples of Market Research Branding Done Right

How do you identify competitors?

You cannot create a competitive business plan without knowing your competitors, that part is obvious. What is less obvious is how to identify the competitors you need to focus on.

When operating online, your planned business could be up against a wide assortment of competitors. It is not just local entities that might be on your radar, it may also be national or even global enterprises you are fighting for a market share. A small company might be battling against hundreds, possibly even thousands of competitors.

If you are in that position, trying to analyze all of these is, well, pretty much impossible for a newcomer to the market with minimal resources. Not only that, but it is also not necessary for a competitive business plan.

With that in mind, it is recommended you place the spotlight on 5-10 relevant competitors, both direct and indirect, to produce an accurate, diverse analysis.

What makes a competitor relevant? Of course, they need to operate in the same sector, yet they should also offer similar products and services to what you plan to feature.

With the power of the internet, finding competitors is a breeze. Simply head to Google or Amazon, input keywords that represent your product/service, and see which organizations appear at the top of the search results. These will typically be your main competitors, and not just from a search engine optimization (SEO) point of view!

Related: 3 Ways to do Market Research with Google

What do you include in a competitive business plan ?

You have found a major competitor. They sell products and services that are similar – or even identical – to what you will offer. Yet, simply comparing this aspect is only one step in truly analyzing the competition. You also must focus on elements such as:

- Estimated market share, including sales numbers and revenue.

- The target market you are focusing on.

- Price comparison between your products/services and the competition.

- Customer reviews rivals have received.

- Marketing strategies used by competitors.

Covering aspects like these are essential for getting the most out of your business plan.

Take a product price comparison. If your competitors are, by and large, selling a similar product at a much lower price than you envisioned, you have a few points to consider. Does your product have the added quality to justify the bump in price?

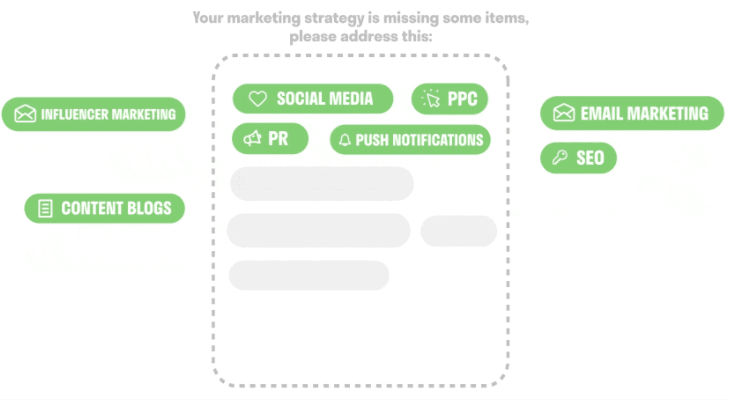

In terms of researching the marketing strategies your competitors use, this can help save your business a lot of time, effort, and finances. You are able to discover the promotional channels that are effective, the ones to put on the back burner, and those which are ripe for experimentation.

The steps to creating your competitive business plan .

You know what a competitive business plan is, how to find competitors, and the type of information to include in this document. However, ample work is necessary to craft a high-quality, effective competitive business plan that will help your company both in the present and future.

To make it a reality, here are the steps you need to take to produce a competitive business plan:

1. Overview of your competitors .

As mentioned above, it is recommended to cover up to ten relevant competitors for your business plan. As well as direct and indirect competitors, a mixture of long-established organizations and fellow startups is advised for a truly diversified analysis.

As the title of this section suggests, it should not delve too deep into the details of each business. This is only an overview of each competitor – the hard work is done later on in the process.

2. Market research .

Now it is time to put in the effort that will ultimately make your competitive business plan worthwhile. In-depth market research comprises numerous components. You need a healthy combination of primary and secondary research. Then with all the information and data collected, this has to be combined and measured accurately.

As for primary market research methods, try out the following:

- Sample the products and services of your competitors

- Perform in-person focus groups

- Get customers to complete an online survey

- Interview customers to gain more insight into their experience

Secondary market research methods can cover the following:

- A study of company records

- Assess the content and structure of competitor websites

- Identify technology and trend developments in your industry

- Factor in the current economic situation

- Read customer reviews

It is true: market research is not something you can do successfully with minimal effort and in just an hour or two. With that said, various tools can help make the task a much more straightforward – and ultimately effective – one. Here are some of our recommendations:

GapScout : It is not all about looking at star ratings. The analysis of customer reviews can reveal a goldmine of information about a company’s products and services. However, discovering the gold within these reviews is time-consuming and tricky. GapScout is the solution.

Our tool, thanks to its specialist AI technology, accelerates the process considerably. It also can identify specific trends, ensuring it uncovers all the valuable data pertaining to a competitor’s product or service.

SEMrush : There are many search engine analysis tools available. One of the best, however, is SEMrush . This can be vital for obtaining SEO-related information like the keywords they use, the backlinks they have pointing back to their website, their most popular web pages, and much more. With this information, you can strengthen your marketing efforts.

SurveyMonkey : If you are on the search for an online survey tool, one of the most popular is SurveyMonkey , and for good reason. With SurveyMonkey, you can create surveys with ease and send these to customers. Once customers complete these surveys, all the data is collated in an easy-to-consume way.

Google Trends : Again, there are countless tools available for discovering the latest trends. Yet if you desire something that combines effectiveness with a price tag that does not go beyond 0, Google Trends is a no-brainer. This free tool allows you to effortlessly find out what users are currently searching for in your industry or topic of choice.

3. Compare and assess .

You have a general viewpoint of the products and services that are offered by the competition. Yet, you cannot simply take a broad approach with such a key element. You need to delve deeper, learning more about each feature and how this compares against what you offer.

With a product, here are the aspects to keep in mind:

- The value it offers

- Number of features

- Ease of use

- Product age range

- Style and design

- Customer support offered

You may not necessarily have to go through all of the above points. You can abbreviate and zone in on the most important features for your competitive business plan. Key aspects are price, features, and overall quality.

It is not just the products or services you want to compare. Another essential factor for any business is marketing, and you should analyze your competitor’s marketing efforts. This includes evaluating their social media, paid ads, email campaigns, product sales copy, and website content.

Again, you want to avoid just a surface analysis of these marketing efforts. You have to dig deep into the promotional strategies of your competitors, answering questions such as these:

- What value are these marketing strategies providing to customers?

- What brand voice are they using?

- What story are they telling with their marketing materials?

- What is the overall mission of the company?

- How successful are they in currently achieving this mission?

Related: 7 Tips when Branding for a Small Business

4. Perform a SWOT analysis .

The nature of a competitive business plan is to study and gather information about your competitors. Nevertheless, you should never lose focus or forget that the plan is built around your business.

This is why a SWOT – Strengths, Weaknesses, Opportunities, and Threats – analysis should be part of your business plan.

With a SWOT analysis, you can uncover your strengths and weaknesses, assess threats, discover possible market gaps, turn any weaknesses into potential opportunities, and more.

Ultimately, it supplies you with a different viewpoint to evaluate your business, giving you additional points to fine-tune your business plan.

The good news: the research you conducted in the previous steps will help significantly with your SWOT analysis.

Related: How to Identify Business Opportunities

5. Understand your competitive position .

With all the work done for your competitive business plan so far, it is time to figure out exactly how your company stacks up against the rest. This is done by understanding your competitive position.

Understanding your position in the competitive landscape gives your business the launch pad to carve out a presence within your target market. This is because it helps you to identify:

- The distinctive differences that make your business different from the rest.

- How you can take advantage of these differences to stand out.

- Your strengths and weaknesses, and how you will work towards the former and hide away the latter.

- The general approach of your business, along with how this will appear to the world.

Position yourself behind a competitor, and you will fail to stand out – which means a lot of lost attention and sales. By recognizing what your business does better than those rivals, you have a selling point, something that will get potential customers to stand up and take notice.

In Conclusion…

Creating a competitive business plan demands a lot of effort on your part. That effort, however, is rewarded in numerous ways. You learn about the competition, you understand what makes them tick, and you can use this information to improve your company’s own standing and long-term future.

A competitive business plan is the best way forward if you want to be successful.

Ready to Automate Your Market Research? Get exclusive access to GapScout prior to release!

Share this:

The best in market research.

Market research tips & tools sent to your inbox.

By clicking Subscribe, you agree to our Terms and Conditions.

Popular Articles

Voice of customer questions for new product development

5 voice of customer examples that you should not ignore

How to perform SWOT analysis of a company

Email us: [email protected] Made with ♥ in sunny California

- Legal Policies

Sign up for early access here!

ⓒ 2023 GapScout. All rights reserved.

Get Early Access!

Sign up to get early beta access to GapScout before it becomes publicly available!

We use cookies to give you the best possible experience on our website.

Want to create or adapt books like this? Learn more about how Pressbooks supports open publishing practices.

3.1 How Do We Define Business Competition?

Perfect competition, supply, and demand.

Under a mixed economy, such as we have in Canada, businesses make decisions about which goods to produce or services to offer and how they are priced. Because there are many businesses making goods or providing services, customers can choose among a wide array of products. The competition for sales among businesses is a vital part of our economic system. Economists have identified four types of competition—perfect competition, monopolistic competition, oligopoly, and monopoly. We’ll introduce the first of these—perfect competition—in this section and cover the remaining three in the following section.

Perfect Competition

Perfect competition exists when there are many consumers buying a standardized product from numerous small businesses. Because no seller is big enough or influential enough to affect price, sellers and buyers accept the going price. For example, when a commercial fisher brings his fish to the local market, he has little control over the price he gets and must accept the going market price.

The Basics of Supply and Demand

To appreciate how perfect competition works, we need to understand how buyers and sellers interact in a market to set prices. In a market characterized by perfect competition, price is determined through the mechanisms of supply and demand. Prices are influenced both by the supply of products from sellers and by the demand for products by buyers.

To illustrate this concept, let’s create a supply and demand schedule for one particular good sold at one point in time. Then we’ll define demand and create a demand curve and define supply and create a supply curve. Finally, we’ll see how supply and demand interact to create an equilibrium price—the price at which buyers are willing to purchase the amount that sellers are willing to sell.

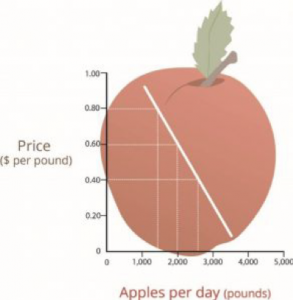

Demand and the Demand Curve

Demand is the quantity of a product that buyers are willing to purchase at various prices. The quantity of a product that people are willing to buy depends on its price. You’re typically willing to buy less of a product when prices rise and more of a product when prices fall. Generally speaking, we find products more attractive at lower prices, and we buy more at lower prices because our income goes further.

Using this logic, we can construct a demand curve that shows the quantity of a product that will be demanded at different prices. Let’s assume that the diagram “The Demand Curve” represents the daily price and quantity of apples sold by farmers at a local market. Note that as the price of apples goes down, buyers’ demand goes up. Thus, if a pound of apples sells for $0.80, buyers will be willing to purchase only fifteen hundred pounds per day. But if apples cost only $0.60 a pound, buyers will be willing to purchase two thousand pounds. At $0.40 a pound, buyers will be willing to purchase twenty-five hundred pounds.

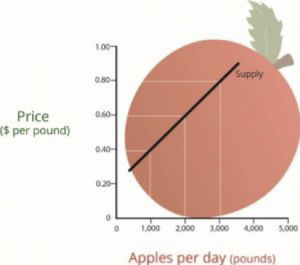

Supply and the Supply Curve

Supply is the quantity of a product that sellers are willing to sell at various prices. The quantity of a product that a business is willing to sell depends on its price. Businesses are more willing to sell a product when the price rises and less willing to sell it when prices fall. Again, this fact makes sense: businesses are set up to make profits, and there are larger profits to be made when prices are high.

Now we can construct a supply curve that shows the quantity of apples that farmers would be willing to sell at different prices, regardless of demand. As you can see in “The Supply Curve”, the supply curve goes in the opposite direction from the demand curve: as prices rise, the quantity of apples that farmers are willing to sell also goes up. The supply curve shows that farmers are willing to sell only a thousand pounds of apples when the price is $0.40 a pound, two thousand pounds when the price is $0.60, and three thousand pounds when the price is $0.80.

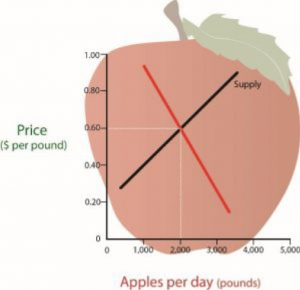

Equilibrium Price

We can now see how the market mechanism works under perfect competition. We do this by plotting both the supply curve and the demand curve on one graph, as we’ve done in the figure below, “The Equilibrium Price” . The point at which the two curves intersect is the equilibrium price.

You can see in “The Equilibrium Price” that the supply and demand curves intersect at the price of $0.60 and quantity of two thousand pounds. Thus, $0.60 is the equilibrium price: at this price, the quantity of apples demanded by buyers equals the quantity of apples that farmers are willing to supply. If a single farmer tries to charge more than $0.60 for a pound of apples, he won’t sell very many because other suppliers are making them available for less. As a result, his profits will go down. If, on the other hand, a farmer tries to charge less than the equilibrium price of $0.60 a pound, he will sell more apples but his profit per pound will be less than at the equilibrium price. With profit being the motive, there is no incentive to drop the price.

Introduction to Management Copyright © by Kathleen Rodenburg is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License , except where otherwise noted.

Share This Book

Benefits of Business Plan Competitions: What You Need to Know

by Dylan Taylor | Apr 20, 2020 | Business |

If you believe you have a strong idea for a business, you likely know you’ll need to draft a business plan before turning your idea into a reality. Along with helping you explain your strategy to investors, a business plan will help provide you with a roadmap to success. Consider submitting your draft to a business plan competition once you’ve finished developing it. The potential benefits of doing so include the following:

Obtaining Funding

Business plan competitions vary widely in their parameters. For example, while some involve directly submitting an established idea, others allow teams of entrepreneurs to create fresh ideas based on prompts. In addition, many business plan competitions provide awards to their winners in the form of seed funding and/or mentorship from successful entrepreneurs and business leaders.

Meeting Mentors

A mentor can play a very important role in your future success. This is particularly true if you’re a new entrepreneur. With an experienced mentor guiding you, you’re less likely to make common errors, and more likely to make the right choices during the early stages of growing your business. A mentor may also help you grow your professional network.

This is another reason to participate in business plan competitions. Very often, they match participating entrepreneurs with mentors. Even if you don’t win the competition, if your mentor is impressed with you, they might be willing to continue mentoring you after the competition is over.

A mentor is by no means the only helpful person you can meet through a business plan competition. Very often, investors also participate in these competitions. Networking with them would of course be a valuable experience. Additionally, you could meet other entrepreneurs through the competition who you may wish to collaborate with in the future.

Building Your Confidence

Don’t worry if you secretly (or not-so-secretly) doubt your own strengths as an entrepreneur. This is a common experience. While it is important to honestly assess both your skills and idea before spending time and money trying to grow a business with limited potential, you shouldn’t necessarily feel discouraged because you lack confidence.

Many successful entrepreneurs have been in your shoes before. Luckily, business plan competition participants often find that the experience provides them with a degree of validation. This helps them fully commit to their goals.

Practicing Important Skills

A business plan competition doesn’t typically consist of judges merely reviewing the written draft of your business plan. In many cases, you also need to develop and present pitches for your business idea.

This gives you the opportunity to develop an important skill. In the future, you’ll almost certainly need to pitch your ideas to investors. Practicing doing so in a low-stakes environment helps you identify what you must do to improve upon your pitch.

Getting New Perspectives

Odds are good your business plan isn’t perfect. Even if your idea is strong, there is always room for improvement

Many entrepreneurs struggle to identify key weaknesses with their ideas that need to be addressed. Fortunately, during a business plan competition, multiple judges will likely evaluate your pitch. Receiving feedback from multiple sources helps you broaden your perspective and more effectively refine your plan in the future.

Impressing Potential Investors

It’s uncommon for reputable business plan competitions to accept submissions from every interested applicant. Judges don’t have the time to review countless plans.

That’s why they carefully assess applications before selecting participants. Thus, if you were accepted into a business plan competition, you could leverage that fact later by mentioning it to investors. Even if you don’t win, they may be impressed that you participated in the first place. This will at least help you get your foot in the door.

Receiving Media Coverage

Depending on the competition you participate in, your idea may receive attention from business media outlets. This of course provides you with free exposure. If the right person hears about your idea, they might approach you with an offer to invest in it.

These are only a few reasons budding entrepreneurs should consider participating in business plan competitions. Just make sure you don’t assume you’ll be accepted to participate in the first competition you apply to. You may need to try several times before you are selected to compete. When you do, however, the benefits can be substantial.

Recent Posts

- Angel Investing vs Venture Capital: What Founders Need to Know

- More Women Are Gaining Prominence in Angel Investing

- Esports Spotlight: Italy

- February 2024

- January 2024

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- January 2020

Lean Business Planning

Get what you want from your business.

Nature of competition

If it isn’t obvious, and you have something to gain from explaining, then start with the general nature of competition in your type of business, and how customers seem to choose one provider over another. What might make customers decide? Price, billing rates, reputation, or image and visibility? Are brand names important? How influential is word of mouth in providing long-term satisfied customers?

For example, competition in the restaurant business might depend on reputation and trends in one part of the market, and on location and parking in another. For the Internet and Internet service providers, busy signals for dial-up customers might be important. A purchase decision for an automobile may be based on style, or speed, or reputation for reliability.

For many professional service practices, the nature of competition depends on word of mouth because advertising is not completely accepted and therefore not as influential. Is there price competition between accountants, doctors, and lawyers? How much difference does a website, or social media engagement, make in choosing professionals?

How do people choose travel agencies or wedding florists? Why does someone hire one landscape architect over another? Why would a customer choose Starbucks, a national brand, over the local coffee house? Why select a Dell computer instead of an Apple? What factors make the most difference for your business? Why? This type of information is invaluable in understanding and explaining the nature of competition.

I’ve seen this done well as a single slide in a pitch presentation. It has a title like “Keys to Success in [your industry].”

Share this:

Leave a comment cancel reply, discover more from lean business planning.

Subscribe now to keep reading and get access to the full archive.

Type your email…

Continue reading

Advertisement

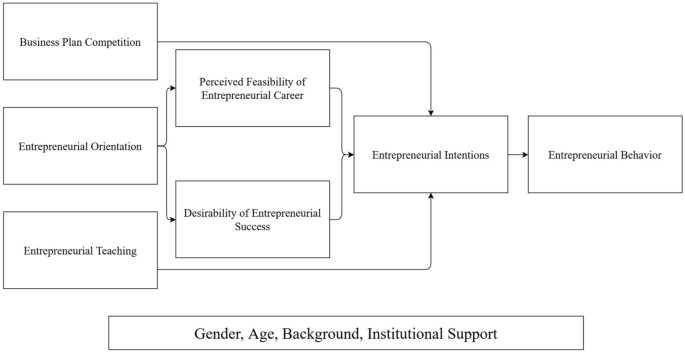

Business plan competitions and nascent entrepreneurs: a systematic literature review and research agenda

- Open access

- Published: 28 February 2023

- Volume 19 , pages 863–895, ( 2023 )

Cite this article

You have full access to this open access article