- Have your assignments done by seasoned writers. 24/7

- Contact us:

- +1 (213) 221-0069

- [email protected]

How to Use Personal Experience in Research Paper or Essay

Personal Experience In Research Writing

Personal experience in academic writing involves using things that you know based on your personal encounter to write your research paper.

One should avoid using personal experience to write an academic paper unless instructed to do so. Suppose you do so, then you should never cite yourself on the reference page.

Some instructions may prompt you to write an essay based on personal experience. Such instances may compel you to write from your personal knowledge as an account for your past encounters over the same topic.

Can you Use Personal Experience in an Essay?

In most of the essays and papers that people write, it is highly recommended that one avoids the use of first-person language. In our guide to writing good essays , we explained that the third person is preferred for academic work.

However, it can be used when doing personal stories or experiences. But can is it possible?

In practice, you can use personal experience in an essay if it is a personal narrative essay or it adds value to the paper by supporting the arguments.

Also, you can use your personal experience to write your academic paper as long as you are writing anything that is relevant to your research.

The only harm about such an essay is that your experience might sound biased because you will be only covering one side of the story based on your perception of the subject.

Students can use the personal story well through a catchy introduction.

Inquire from the instructor to offer you more directions about the topic. However, write something that you can remember as long as you have rich facts about it.

People Also Read: Can Research Paper be Argumentative: How to write research arguments

How to Use Personal Experience in a Research Paper

When you are crafting your easy using your personal experience, ensure you use the first-person narrative. Such a story includes the experiences you had with books, situations, and people.

For you to write such a story well, you should find a great topic. That includes thinking of the events in your life encounters that can make a great story.

Furthermore, you should think of an event that ever happened to you. Besides, you can think of special experiences you had with friends, and how the encounter changed your relationship with that specific person.

The right personal experience essay uses emotions to connect with the reader. Such an approach provokes the empathic response. Most significantly, you can use sensory details when describing scenes to connect with your readers well.

Even better, use vivid details and imagery to promote specificity and enhance the picture of the story you are narrating.

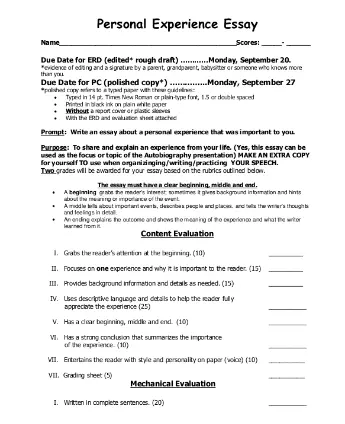

Structure of the Essay

Before you begin to write, brainstorm and jot down a few notes. Develop an outline to create the direction of the essay story.

Like other essays, you should use the introduction, the body, and a conclusion. Let your introduction paragraph capture the reader’s attention.

In other words, it should be dramatic. Your essay should allow the audience to know the essence of your point of view.

Let the body of this essay inform the reader with clear pictures of what occurred and how you felt about it.

Let the story flow chronologically or group the facts according to their importance. Use the final paragraph to wrap up and state the key highlights of the story.

Make it Engaging

The right narrative needs one to use interesting information engagingly. Record yourself narrating the story to assist you in organizing the story engagingly. Furthermore, you are free to use dialogue or anecdotes. For that reason, think about what other people within your story said.

Moreover, you should use transition words for better sentence connections. Again, you should vary the sentence structures to make them more interesting. Make the words as lively and as descriptive as possible.

People Also Read: Can Research Paper Use Bullet Points: when & How to Use them

The Value of Personal Experience

We use personal experience to connect your artwork with your readers since they are human and they would prefer real stories. You will become more realistic when you describe emotions, feelings, and events that happened to you.

Your wealth of personal experience in a specific field will offer you a great advantage when you want to connect all the facts into a useful story.

People Also Read: What is a Background in an Essay: Introducing Information

Reinforcing your Writing Skills

Some students may have brilliant ideas and fail to capture them on paper properly. Some seek to write personal issues but also want to remove first-person language from their writing. This is not good.

However, you can sharpen your writing skills in this aspect. One can use the following tips to make your personal research paper readable and more appealing:

1. Sharpen grammar

The readability and clarity of your content will rely on grammar.

For that reason, you should polish your spelling, grammar skills, and punctuation daily.

Moreover, you should practice regularly and make the essay more appealing.

2. Expand Vocabulary

It can be helpful if you expand your vocabulary to describe your events successfully. Using better word choice enable the writer to connect with the topic well.

3. Have a Diary

Having a personal diary helps you by boosting your memory about past memorable events. That ensures that you do not lose hold of something important that happened in your past encounter.

4. Systematize it

Make your narration appear systematic to improve the flow. For example, you can divide your experiences in particular importance, emotions, events, people, and so on.

5. Interpret your feelings

It is not a walkover for one to remember every feeling he or she encountered when particular events happened. One should try to analyze and interpret them for better and more effective delivery when writing about personal experiences.

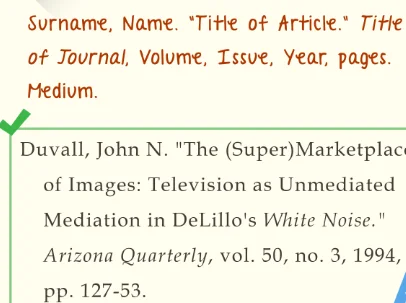

Can you Cite yourself or Personal Experience?

You cannot cite yourself or reference your personal experience because it is your own narration and not data, facts, or external information. Ideally, one does not need to cite personal experiences when using any writing style whether APA or MLA.

It will be unprofessional if you cite yourself in your research paper. Such an experience is your voice which you are bringing to the paper.

Choose the relevant essay based on your essay.

People Also Read: Best Research Paper Font and Size: Best Styles for an Essay

Instances when to use Personal Experience in a Research Paper

There are many instances when you have to apply personal narrations in an essay. In these instances, the use of first language is important. Let us explore them.

1. Personal essays

You can use personal essays in academic writing to engage readers. It makes your writing to be credible and authentic because you will be engaging readers with your writing voice. Some stories are better told when given from personal encounters.

The secret lies in choosing the most relevant topic that is exciting and triggers the right emotions and keeps your audience glued to it. You can include some dialogue to make it more engaging and interesting.

2. Required by the instructions

Some situations may prompt your professor to offer students instructions that compel them to write a research paper based on a personal encounter. Here, you have to follow the instructions to the latter for you to deliver and earn a good score well.

One way of winning the heart of your professor is to stick to the given instructions. You should relate your past events with the topic at hand and use it to connect with your readers in an engaging manner.

3. Personal Research Report

When you are doing research that involves your personal encounter, you will have to capture those events that can reveal the theme of your topic well.

Of course, it is an account of your perception concerning what you went through to shape your new understanding of the event.

A personal research report cannot be about someone’s also experience. It states the details of what you encountered while handling the most memorable situations.

4. Ethnography Reports

Such a report is qualitative research where you will immerse yourself in the organization or community and observe their interactions and behavior. The narrator of the story must use his perception to account for particular issues that he may be tackling in the essay.

Ethnography helps the author to give first-hand information about the interactions and behavior of the people in a specific culture.

When you immerse yourself in a particular social environment, you will have more access to the right and authentic information you may fail to get by simply asking.

We use ethnography as a flexible and open method to offer a rich narrative and account for a specific culture. As a researcher, you have to look for facts in that particular community in various settings.

When not handling complex essays and academic writing tasks, Josh is busy advising students on how to pass assignments. In spare time, he loves playing football or walking with his dog around the park.

Related posts

Writing a College Admission Essay

Is College Essay Mandatory: Universities It’s not an Option

Writing honors college essay

Honors College Essay: Tips, Prompt Examples and How to Write

Guide to writing narrative essay

How to Write a Narrative Essay: A Stepwise Guide and Length

- Walden University

- Faculty Portal

Scholarly Voice: First-Person Point of View

First-person point of view.

Since 2007, Walden academic leadership has endorsed the APA manual guidance on appropriate use of the first-person singular pronoun "I," allowing the use of this pronoun in all Walden academic writing except doctoral capstone abstracts, which should not contain first person pronouns.

In addition to the pointers below, APA 7, Section 4.16 provides information on the appropriate use of first person in scholarly writing.

Inappropriate Uses: I feel that eating white bread causes cancer. The author feels that eating white bread causes cancer. I found several sources (Marks, 2011; Isaac, 2006; Stuart, in press) that showed a link between white bread consumption and cancer. Appropriate Use: I surveyed 2,900 adults who consumed white bread regularly. In this chapter, I present a literature review on research about how seasonal light changes affect depression.

Confusing Sentence: The researcher found that the authors had been accurate in their study of helium, which the researcher had hypothesized from the beginning of their project. Revision: I found that Johnson et al. (2011) had been accurate in their study of helium, which I had hypothesized since I began my project.

Passive voice: The surveys were distributed and the results were compiled after they were collected. Revision: I distributed the surveys, and then I collected and compiled the results.

Appropriate use of first person we and our : Two other nurses and I worked together to create a qualitative survey to measure patient satisfaction. Upon completion, we presented the results to our supervisor.

Make assumptions about your readers by putting them in a group to which they may not belong by using first person plural pronouns. Inappropriate use of first person "we" and "our":

- We can stop obesity in our society by changing our lifestyles.

- We need to help our patients recover faster.

In the first sentence above, the readers would not necessarily know who "we" are, and using a phrase such as "our society " can immediately exclude readers from outside your social group. In the second sentence, the author assumes that the reader is a nurse or medical professional, which may not be the case, and the sentence expresses the opinion of the author.

To write with more precision and clarity, hallmarks of scholarly writing, revise these sentences without the use of "we" and "our."

- Moderate activity can reduce the risk of obesity (Hu et al., 2003).

- Staff members in the health care industry can help improve the recovery rate for patients (Matthews, 2013).

Pronouns Video

- APA Formatting & Style: Pronouns (video transcript)

Related Resources

Didn't find what you need? Email us at [email protected] .

- Previous Page: Point of View

- Next Page: Second-Person Point of View

- Office of Student Disability Services

Walden Resources

Departments.

- Academic Residencies

- Academic Skills

- Career Planning and Development

- Customer Care Team

- Field Experience

- Military Services

- Student Success Advising

- Writing Skills

Centers and Offices

- Center for Social Change

- Office of Academic Support and Instructional Services

- Office of Degree Acceleration

- Office of Research and Doctoral Services

- Office of Student Affairs

Student Resources

- Doctoral Writing Assessment

- Form & Style Review

- Quick Answers

- ScholarWorks

- SKIL Courses and Workshops

- Walden Bookstore

- Walden Catalog & Student Handbook

- Student Safety/Title IX

- Legal & Consumer Information

- Website Terms and Conditions

- Cookie Policy

- Accessibility

- Accreditation

- State Authorization

- Net Price Calculator

- Contact Walden

Walden University is a member of Adtalem Global Education, Inc. www.adtalem.com Walden University is certified to operate by SCHEV © 2024 Walden University LLC. All rights reserved.

How can I use my own personal experiences as a reference in my research paper?

It is very tempting to want to use things that we know based on our own personal experiences in a research paper. However, unless we are considered to be recognized experts on the subject, it is unwise to use our personal experiences as evidence in a research paper. It is better to find outside evidence to support what we know to be true or have personally experienced.

If it is not possible to find outside evidence, then you will have to construct your paper in such a way as to show your reader that you are an expert on the topic. You would need to lay out your credentials for the reader so that the reader will be able to trust the undocumented evidence that you are providing. This can be risky and is not recommended for research based papers. But even if you do use your own experiences, you would not add yourself to your References page.

Sometimes you will be assigned to write a paper that is based on your experiences or on your reaction to a piece of writing, in these instances it would be appropriate to write about yourself and your personal knowledge. However, you would still never cite yourself as a source on your References page.

For assistance with APA citations, visit the APA Help guide.

Thank you for using ASK US. For further assistance, please contact your Baker librarians .

- Last Updated Oct 26, 2021

- Views 53142

- Answered By Baker Librarians

FAQ Actions

- Share on Facebook

Comments (0)

We'll answer you within 3 hours m - f 8:00 am - 4:00 pm..

An official website of the United States government

The .gov means it’s official. Federal government websites often end in .gov or .mil. Before sharing sensitive information, make sure you’re on a federal government site.

The site is secure. The https:// ensures that you are connecting to the official website and that any information you provide is encrypted and transmitted securely.

- Publications

- Account settings

Preview improvements coming to the PMC website in October 2024. Learn More or Try it out now .

- Advanced Search

- Journal List

- Front Psychol

- PMC10350497

Self-talk: research challenges and opportunities

Thomas m. brinthaupt.

1 Department of Psychology, Middle Tennessee State University, Murfreesboro, TN, United States

Alain Morin

2 Department of Psychology, Mount Royal University, Calgary, AB, Canada

In this review, we discuss major measurement and methodological challenges to studying self-talk. We review the assessment of self-talk frequency, studying self-talk in its natural context, personal pronoun usage within self-talk, experiential sampling methods, and the experimental manipulation of self-talk. We highlight new possible research opportunities and discuss recent advances such as brain imaging studies of self-talk, the use of self-talk by robots, and measurement of self-talk in aphasic patients.

Introduction

In this paper we synthesize past and current research findings pertaining to the phenomenon of self-talk , the activity of talking to oneself out loud or in silence ( Brinthaupt et al., 2009 ). The latter is usually called inner speech , which can be defined as “inner language in the absence of overt and audible articulation” ( Langland-Hassan, 2021 , p. 2). We include in this definition various related constructs such as internal monologue (talking to oneself as one person) or dialogue (having a back-and-forth conversation with oneself), private speech , and self-statements ( Morin, 2012 , 2019 ). Self-talk has a long history of theoretical and empirical work (see Vygotsky, 1943/1962 ; Morin, 2009 ; Gacea, 2019 ). There is a great deal of work pertaining to the development, cognitive functions, phenomenology, and neurobiology of self-talk (e.g., Sokolov, 1972 ; Alderson-Day and Fernyhough, 2015 ). In recent years, the study of self-talk has been steadily progressing: Latinjak et al. (2023) found 559 articles published between 1978 and 2020 that specifically mentioned “self-talk.”

This large body of work allows for the identification of the main functions of self-talk. These include thinking, problem solving, self-regulation, self-reflection, working memory, task switching, language, rehearsal and replay, emotional expression, thinking about others’ mental states, and self-rumination (see Morin and Racy, 2022 , Table 9.1). The array of functions served by self-talk, coupled with the finding that it is present in a significant portion of sampled conscious experiences ( Heavey and Hurlburt, 2008 ), makes it clear that self-talk represents a crucial mental activity.

In this review, we discuss some of the major challenges of studying self-talk, including measurement issues and attempts at assessing self-talk frequency, distinguishing self-talk from other common inner experiences, the study of self-talk in its natural context, and the experimental manipulation of self-talk. We also examine research opportunities and recent advances such as the use of thought sampling procedures to assess self-talk, brain imaging studies of different types and formats of self-talk, the use of self-talk by robots to increase trust during human-robot interactions, and measurement of self-talk in aphasic patients.

Measurement challenges and opportunities

In our chapter on self-talk assessment in sport ( Brinthaupt and Morin, 2020 ; see Table 3.2), we discuss the main advantages and limitations of most existing self-talk measures (also see Morin and Racy, 2022 , Table 9.2). Commonly used self-talk measures include (1) self-report inventories such as the Self-Talk Scale (STS; Brinthaupt et al., 2009 ) and the Varieties of Inner Speech Questionnaire—Revised (VISQ-R; Alderson-Day et al., 2018 ); Descriptive Experiential Sampling (DES) (e.g., Heavey and Hurlburt, 2008 ); recordings of brain activity (e.g., Kühn et al., 2014 ); think aloud (e.g., Klopp et al., 2020 ) and thought listing (e.g., Morin et al., 2018 ) protocols; and observer recordings of self-talk manifestations (e.g., Sokolov, 1972 ; Van Raalte et al., 1994 ; Winsler, 2009 ). Less traditional approaches include videotape reconstruction (e.g., Asendorpf, 1987 ), one-on-one interviews (e.g., Latinjak et al., 2019 ), and various experimental methods designed to interfere with self-talk or show self-talk deficits (e.g., Holland and Low, 2010 ; Tullett and Inzlicht, 2010 ; Langland-Hassan et al., 2015 ).

Each method has its strengths and weaknesses. For example, thought listing, interviews, and self-talk recordings are best suited for assessing self-talk content, whereas observer reports and recordings of brain activity tap into the frequency/occurrence of self-talk. The DES approach, recordings of ongoing private speech, and videotape reconstruction offer greater ecological validity compared to interviews or self-report questionnaires. Methods that interfere experimentally with the self-talk process can have more direct control over the nature and content of self-talk compared to thought listing or self-report questionnaires. Self-report methods are easy to use, whereas DES and brain imaging require significantly more time and effort. For more detailed reviews of reliability and validity issues with self-talk measures, see Van Raalte et al. (2019) and Brinthaupt and Morin (2020) .

We note two key observations from our review of self-talk measures. First, assessing self-talk in situ is difficult—one can adopt methods like private speech recording and DES, but these are either prone to multiple biases (which can affect validity) or are complicated to implement. Second, researchers often must rely on retrospective self-talk descriptions: as soon as a self-report becomes retrospective (even in the short term), it becomes potentially inaccurate because of possible memory biases. There is debate over whether self-report measures inflate actual frequencies of self-talk, as suggested by Hurlburt et al. (2022) . Issues with self-report questionnaires, which might possibly bias results pertaining to frequency, include individual differences in interpretating Likert scales (e.g., what does it mean to talk to oneself “rarely” or “often”?) and vagueness or complexity of items (e.g., from the VISQ-R: “When I am talking to myself about things in my mind, it is like I am having a conversation with myself”).

Methodological challenges and opportunities

There are multiple methodological challenges in self-talk research. Studying the phenomenon in its natural context frequently requires disrupting the flow of the self-talk. For example, self-talk may be “automatic” and outside of our awareness (e.g., Beck, 1976 ), making it difficult to study in situ. Research shows that creating specific self-talk cues or prompts can be effective when learning to meet specific performance goals (e.g., Cutton and Burt, 2023 ). However, there are potential problems with asking people to recite researcher-determined self-talk and studying its resulting effects. First, such content might not occur naturally in the course of a person’s customary self-talk patterns. Second, the unique nature or style with which people talk to themselves might differ from researcher-provided cue or prompts. In response to these challenges, researchers have developed innovative ways to examine the nature, frequency, and content of self-talk.

One research approach tries to study ongoing (or nearly concurrent) instances of self-talk using experience sampling methods (ESM). Participants typically receive a series of random signals (e.g., via phone or some other device) during their regular daily activities. As soon as possible, they report the content of their inner experiences upon receiving the signal. Researchers have used ESM to validate self-talk measures (e.g., Brinthaupt et al., 2015 ) and to sample ongoing athletic activity ( Dickens et al., 2018 ). Despite the experience “closeness” of these methods, they still require some degree of interpretation and reporting from the participants that might be susceptible to biases.

A different line of research involves the use of personal pronouns in self-talk. For example, research on “self-distancing” (e.g., Ayduk and Kross, 2010 ; White et al., 2019 ) compares the effects of 3rd-person to 1st-person self-talk by asking participants to narrate a personal event with “they/he/she” or with “I/me.” Results show that the increased self-distancing created by 3rd-person self-talk has positive coping effects when people reflect on both past and future negative events. However, it could be argued that this kind of self-talk is unusual and does not typically occur very often naturalistically (i.e., most people typically use first-person “I” in their self-talk; see Bisol, 2021 ). A related area that has yet to be explored is individual differences in preference for personal pronouns and how these might relate to personality traits.

Another possibility, which has been underutilized in the research literature, is to ask participants to imagine a specific personal or social situation and then report verbatim the kinds of things they would say to themselves as that situation occurs or in response to it having happened. This approach has the potential to provide insight into participants’ typical patterns of self-talk when different kinds of events occur. Some researchers (e.g., Kittani and Brinthaupt, 2023 ; Łysiak et al., 2023 ) have asked participants to retrospect about different kinds of prior events (e.g., difficult, negative, or positive) and then report the self-talk and internal dialogues associated with those events. There is also work examining self-talk using prospective or hypothetical situations (e.g., Silk et al., 2020 ).

Researchers using retrospective or hypothetical approaches must be cognizant of the possibility of biases entering into the self-talk that participants recall or imagine (e.g., Latinjak et al., 2011 ). Exploring the nature of such potential biases might have important research implications for self-talk processes. For example, when people recall what they may have said to themselves in response to a past situation or event, researchers might examine the extent to which their subsequent thoughts, emotions, and behaviors are likely to be based on what they think happened versus what actually happened.

Frequency of self-talk

This section is designed to highlight some of the ways that measuring self-talk frequency presents specific research challenges and opportunities. A major challenge in self-talk research has been to quantify the frequency of self-talk ( Brinthaupt et al., 2009 ). A paper by Hurlburt et al. (2022) suggests that, compared to DES frequency results, self-report measures such as the STS over-report actual frequencies of self-talk. We submit that this assertion constitutes an “apples to oranges” comparison fallacy. DES data, if accurate, can only indicate whether volunteers are talking to themselves at specific moments when they are probed, whereas questionnaire data reflect self-talk use in response to specific situations, using subjective frequency scales, and should not be converted to any absolute or relative frequency counts.

Descriptive Experiential Sampling involves a post-data collection interview aimed at double-checking the accuracy of participants’ reports of inner experiences. More fruitful research avenues include examining the effects of a DES interview on subsequent frequency of self-talk reports. Participants might exhibit significant declines in their self-reported self-talk scores after undergoing the DES interview compared to before doing so. That is, they might realize that they talk less often to themselves than they assume.

Self-talk interventions in the sport and clinical domains often rely on the introduction of new or different kinds of self-talk content and studying the effects of that content. For example, an important element of cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT; Turner et al., 2020 ; Beck, 2021 ) is to help people identify their dysfunctional self-talk and then guide them toward replacing those instances with more positive, adaptive, rational, or realistic interpretations of events. There is strong evidence that this approach can be effective with a variety of psychological disorders (e.g., Hofmann et al., 2012 ). The focus of CBT is on the content of people’s self-talk, rather than with individual differences in the frequency of their everyday self-talk.

One area for future clinical research is to explore whether people who report talking to themselves very often in response to specific situations find it easier to benefit from CBT. Given that CBT aspires to change clients’ negative self-talk (e.g., Luo and McAloon, 2021 ), it seems logical that individuals who report more frequent self-talk will respond more quickly and favorably to CBT interventions than those who report infrequent self-talk. On the other hand, Van Raalte et al.’s (2016) sport-specific self-talk model predicts that the intentional use of self-talk can deplete a person’s cognitive resources. This suggests that clients whose frequency of intentionally used self-talk is so high that it causes cognitive depletion may be less able to use or benefit from CBT interventions than those with a lower frequency or less cognitively depleting self-talk. It would also be interesting to study how participating in CBT affects people’s awareness of and overall frequency of subsequent self-talk.

Brain localization of self-talk activity

Early attempts to locate self-talk activity in the brain involved recording neural activity using Positron Emission Tomography (PET) and functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) scans while participants were silently reading single words or sentences, or when they engaged in working memory tasks requiring covert repetition of verbal material (e.g., McGuire et al., 1996 ; Baciu et al., 1999 ; Geva et al., 2011 ). The LIFG within Broca’s area is reliably activated during such simple covert self-talk tasks. Corroborating studies showed that accidental damage to the LIFG, or temporary disruption of LIFG activity using Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS), leads to self-talk disruption (e.g., Verstichel et al., 1997 ; Aziz-Zadeh et al., 2005 ). Other studies looking at in-depth brain activation identified additional brain areas associated with self-talk production, such as Wernicke’s area, the supplementary motor area, insula, left superior parietal lobe, and right posterior cerebellar cortex (e.g., Perrone-Bertolotti et al., 2014 ).

Of course, self-talk is more than the mere silent reciting of words or sentences. More recent work has examined several variations in self-talk, such as in task-elicited compared to spontaneous self-talk, where the former was linked to decreased activation in Heschl’s gyrus and increased activation in the LIFG, while the latter had the opposite effect in Heschl’s gyrus and no significant effect in LIFG ( Hurlburt et al., 2016 ). Compared to monologic self-talk, dialogic self-talk recruits a broader bilateral group of brain areas, some of which (e.g., right posterior superior temporal gyrus) are also activated when thinking about others’ mental states ( Alderson-Day et al., 2016 ). More recently, Stephan et al. (2020) contrasted inner and overt speech using electroencephalography (EEG) and observed an inhibition of motor areas normally recruited during articulation.

Several research opportunities exist, where a comparison of differential brain activation will likely be noted between different forms of self-talk, including spontaneous, goal-directed, cue-based (instructional), and 1st-person compared to 3rd-person self-talk. To date, researchers have only begun examining how different forms of self-talk are localized in the brain. It is worth noting that while the above line of research is very informative regarding the neural substrates of self-talk, it tells us little about naturally occurring self-talk frequency and content. Recent small and portable ambulatory devices measuring brain activity occurring in natural environments have been developed (see Boto et al., 2018 ), which most likely will make it possible to identify the brain areas activated during naturally occurring self-talk.

Research opportunities moving forward

In this last section, we outline a few additional research ideas and current advances pertaining to the phenomenon of self-talk. One opportunity consists in being more creative when using the DES method. For example, Dickens et al. (2018) recorded the actual content of self-talk each time probed participants reported an experience and examined activities participants were engaged in when hearing the beep. One prediction is that complex or challenging activities will generate more self-talk of a problem-solving nature, compared to trivial or repetitive tasks ( Brinthaupt, 2019 ).

Work on self-talk is now permeating Artificial Intelligence research. Pipitone and Chella (2021) and Pipitone et al. (2021) have been trying to enhance human-robot cooperation via self-talk. Humans are exposed to a robot’s self-talk (i.e., human-like self-talk that is programmed into robots) during human-robot interactions. As a result of this exposure, humans are presumed to perceive the robot’s internal processes, and this is thought to increase transparency, trust, and cooperation. Preliminary results are encouraging.

Another fertile research area consists in the study of covert self-talk (inner speech) in aphasics—patients suffering from various language deficits following brain insult. Research on self-talk in aphasics offers interesting new theoretical avenues for brain localization and the relationship between interpersonal and intrapersonal communications. One main question is: do these patients, who exhibit problems with spoken language, experience similar difficulties with covert speech? Although the answer to this question varies depending on which method is used to assess inner speech ( Fama and Turkeltaub, 2020 ), the trend is that covert speech is often preserved (e.g., Fama et al., 2019 ; Alexander et al., 2023 ), suggesting that overt and inner speech are clinically dissociable, with the latter being more resistant to brain damage. This research also shows that subjective and objective measures of self-talk are closely related with this population. Stark and colleagues, as well as Fama’s research team, are currently developing self-report measures of self-talk adapted to an aphasic population based on Racy et al. (2019) ’s General Inner Speech Questionnaire (B. Stark, personal communication, January 2, 2023; M. Fama, personal communication, January 20, 2023). This emerging research on aphasics illustrates the potential value of studying when self-talk “goes wrong” or is damaged.

In conclusion, we believe that continued interest in studying the various features of self-talk is warranted. There are many interesting aspects of the phenomenon that have yet to be fully explored. Although there are several methodological and measurement challenges to conducting research on self-talk, recent work offers much promise for additional theoretical developments and new interesting findings.

Author contributions

Both authors listed have made a substantial, direct, and intellectual contribution to the work, and approved it for publication.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

- Alderson-Day B., Fernyhough C. (2015). Inner speech: Development, cognitive functions, phenomenology, and neurobiology. Psychol. Bull. 141 931–965. 10.1037/bul0000021 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alderson-Day B., Mitrenga K., Wilkinson S., McCarthy-Jones S., Fernyhough C. (2018). The varieties of inner speech questionnaire—Revised (VISQ-R): Replicating and refining links between inner speech and psychopathology. Conscious. Cogn. 65 48–58. 10.1016/j.concog.2018.07.001 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alderson-Day B., Weis S., McCarthy-Jones S., Moseley P., Smailes D., Fernyhough C. (2016). The brain’s conversation with itself: Neural substrates of dialogic inner speech. Soc. Cogn. Affect. Neurosci. 11 110–120. 10.1093/scan/nsv094 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Alexander J. M., Langland-Hassan P., Stark B. C. (2023). Measuring inner speech objectively and subjectively in aphasia . Open Sci. Framework. 10.17605/OSF.IO/8SJNY [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Asendorpf J. B. (1987). Videotape reconstruction of emotions and cognitions related to shyness. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 53 542–549. 10.1037//0022-3514.53.3.542 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Ayduk Ö, Kross E. (2010). From a distance: Implications of spontaneous self-distancing for adaptive self-reflection. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 98 809–829. 10.1037/a0019205 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Aziz-Zadeh L., Cattaneo L., Rochat M., Rizzolatti G. (2005). Covert speech arrest induced by rTMS over both motor and nonmotor left hemisphere frontal sites. J. Cogn. Neurosci. 17 928–938. 10.1162/0898929054021157 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Baciu M. V., Rubin C., Décorps M. A., Segebarth C. M. (1999). fMRI assessment of hemispheric language dominance using a simple inner speech paradigm. NMR Biomed. 12 293–298. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck A. T. (1976). Cognitive therapy and the emotional disorders. New York, NY: New American Library. [ Google Scholar ]

- Beck J. S. (2021). Cognitive behavior therapy: Basics and beyond , 3rd Edn. New York, NY: Guilford Publications. [ Google Scholar ]

- Bisol S. M. (2021). How do you talk to yourself? – The effects of pronoun usage and interpersonal qualities of self-talk. Unpublished Master’s thesis. Available online at: https://scholars.wlu.ca/etd/2364/ (accessed March 12, 2023). [ Google Scholar ]

- Boto E., Holmes N., Leggett J., Roberts G., Shah V., Meyer S. S., et al. (2018). Moving magnetoencephalography towards real-world applications with a wearable system. Nature 555 657–661. 10.1038/nature26147 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brinthaupt T. M. (2019). Individual differences in self-talk frequency: Social isolation and cognitive disruption. Front. Psychol. Cogn. Sci. 10 : 1088 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01088 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brinthaupt T. M., Morin A. (2020). “ Assessment methods for organic self-talk ,” in Self-talk in sport , eds Latinjak A., Hatzigeorgiadis A. (Abingdon: Routledge; ), 28–50. 10.4324/9780429460623-3 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brinthaupt T. M., Benson S. A., Kang M., Moore Z. D. (2015). Assessing the accuracy of self-reported self-talk. Front. Psychol. 6 : 570 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00570 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Brinthaupt T. M., Hein M. B., Kramer T. E. (2009). The Self-Talk Scale: Development, factor analysis, and validation. J. Pers. Assess. 91 82–92. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Cutton D. M., Burt D. J. (2023). Implementation of self-talk cues for university instructional physical activity programs as a best practice approach. J. Phys. Educ. Recreation Dance 94 32–37. 10.1080/07303084.2022.2136309 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Dickens Y. L., Van Raalte J., Hurlburt R. T. (2018). On investigating self-talk: A descriptive experience sampling study of inner experience during golf performance. Sport Psychol. 32 66–73. 10.1123/tsp.2016-0073 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fama M. E., Turkeltaub P. E. (2020). Inner speech in aphasia: Current evidence, clinical implications, and future directions. Am. J. Speech Lang. Pathol. 29 560–573. 10.1044/2019_AJSLP-CAC48-18-0212 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Fama M. E., Snider S. F., Henderson M. P., Hayward W., Friedman R. B., Turkeltaub P. E. (2019). The subjective experience of inner speech in aphasia is a meaningful reflection of lexical retrieval. J. Speech Lang. Hear. Res. 62 106–122. 10.1044/2018_JSLHR-L-18-0222 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Gacea A. O. (2019). “ Plato and the “internal dialogue”: An ancient answer for a new model of the self ,” in Psychology and ontology in Plato, philosophical studies series , Vol. 139 eds Pitteloud L., Keeling E. (Cham: Springer International Publishing; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Geva S., Jones P. S., Crinion J. T., Price C. J., Baron J.-C., Warburton E. A. (2011). The neural correlates of inner speech defined by voxel-based lesion–symptom mapping. Brain 134 3071–3082. 10.1093/brain/awr232 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Heavey C. L., Hurlburt R. T. (2008). The phenomena of inner experience. Conscious. Cogn. 17 798–810. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hofmann S. G., Asnaani A., Vonk I. J., Sawyer A. T., Fang A. (2012). The efficacy of cognitive behavioral therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Cogn. Ther. Res. 36 427–440. [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Holland L., Low J. (2010). Do children with autism use inner speech and visuospatial resources for the service of executive control? Evidence from suppression in dual tasks. Br. J. Dev. Psychol. 28 369–391. 10.1348/026151009X424088 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hurlburt R. T., Alderson-Day B., Kühn S., Fernyhough C. (2016). Exploring the ecological validity of thinking on demand: Neural correlates of elicited vs. spontaneously occurring inner speech. PLoS One 11 : e0147932 . 10.1371/journal.pone.0147932 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Hurlburt R. T., Heavey C. L., Lapping-Carr L., Krumm A. E., Moynihan S. A., Kaneshiro C., et al. (2022). Measuring the frequency of inner-experience characteristics. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 17 559–571. [ PubMed ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Kittani S. R., Brinthaupt T. M. (2023). Exploring self-talk in response to disruptive and emotional events . J. Constr. Psychol. 10.1080/10720537.2023.2194691 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Klopp E., Schneider J. F., Stark R. (2020). Thinking aloud: The mind in action. Weimar: Bertuch Verlag GmbH. [ Google Scholar ]

- Kühn S., Fernyhough C., Alderson-Day B., Hurlburt R. T. (2014). Inner experience in the scanner: Can high fidelity apprehensions of inner experience be integrated with fMRI? Front. Psychol. 9 : 1393 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2014.01393 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Langland-Hassan P. (2021). Inner speech. WIREs Cogn. Sci. 12 : e1544 . 10.1002/wcs.1544 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Langland-Hassan P., Faries F. R., Richardson M. J., Dietz A. (2015). Inner speech deficits in people with aphasia. Front. Psychol. 6 : 528 . 10.3389/fpsyg.2015.00528 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Latinjak A. T., Morin A., Brinthaupt T. M., Hardy J., Hatzigeorgiadis A., Kendall P. C., et al. (2023). Self-talk: An interdisciplinary review and transdisciplinary model. Rev. Gen. Psychol. [ Google Scholar ]

- Latinjak A. T., Torregrosa M., Renom J. (2011). Combining self-talk and performance feedback: Their effectiveness with adult tennis players. Sport Psychol. 25 18–31. 10.1123/tsp.25.1.18 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Latinjak A. T., Torregrossa M., Comoutos N., Hernando-Gimeno C., Ramis Y. (2019). Goal-directed self-talk used to self-regulate in male basketball competitions. J. Sports Sci. 37 1429–1433. 10.1080/02640414.2018.1561967 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Luo A., McAloon J. (2021). Potential mechanisms of change in cognitive behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety: A meta-analysis. Depress. Anxiety 38 220–232. 10.1002/da.23116 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Łysiak M., Puchalska-Wasyl M. M., Jankowski T. (2023). Dialogues between distanced and suffering I-positions: Emotional consequences and self-compassion. J. Constr. Psychol. 1–14. [ Google Scholar ]

- McGuire P. K., Silbersweig D. A., Wright I., Murray R. M., Frackowiak R. S. J., Frith C. D. (1996). The neural correlates of inner speech and auditory verbal imagery in schizophrenia: Relationship to auditory verbal hallucinations. Br. J. Psychiatry 169 148–159. 10.1192/bjp.169.2.148 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morin A. (2009). “ Inner speech and consciousness ,” in Encyclopedia of consciousness , ed. Banks W. (Amsterdam: Elsevier; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Morin A. (2012). “ Inner speech ,” in Encyclopedia of human behavior , 2nd Edn, ed. Hirstein W. (San Diego, CA: Elsevier; ), 436–443. [ Google Scholar ]

- Morin A. (2019). When inner speech and imagined interactions meet. Imagin. Cogn. Pers. 39 374–385. 10.1177/0276236619864276 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Morin A., Racy F. (2022). “ Frequency, content, and functions of self-reported inner speech in young adults: A synthesis ,” in Inner speech, culture & education , ed. Fossa P. (Cham: Springer; ). [ Google Scholar ]

- Morin A., Duhnych C., Racy F. (2018). Self-reported inner speech use in university students. Appl. Cogn. Psychol. 32 376–382. 10.1002/acp.3404 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Perrone-Bertolotti M., Rapin L., Lachaux J. P., Baciu M., Loevenbruck H. (2014). What is that little voice inside my head? Inner speech phenomenology, its role in cognitive performance, and its relation to self- monitoring. Behav. Brain Res. 261 220–239. 10.1016/j.bbr.2013.12.034 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pipitone A., Chella A. (2021). What robots want? Hearing the inner voice of a robot. iScience 24 : 102371 . 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102371 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Pipitone A., Geraci A., D’Amico A., Seidita V., Chella A. (2021). Robot’s inner speech effects on trust and anthropomorphic cues in human-robot cooperation. arXiv [preprint]. arXiv:2109.09388. [ Google Scholar ]

- Racy F., Morin A., Duhnych C. (2019). Using a thought listing procedure to construct the general inner speech questionnaire: An ecological approach. J. Constr. Psychol. 33 385–405. 10.1080/10720537.2019.1633572 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Silk J. S., Pramana G., Sequeira S. L., Lindhiem O., Kendall P. C., Rosen D., et al. (2020). Using a smartphone app and clinician portal to enhance brief cognitive behavioral therapy for childhood anxiety disorders. Behav. Ther. 51 69–84. 10.1016/j.beth.2019.05.002 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Sokolov A. N. (1972). Inner speech and thought. New York, NY: Plenum Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- Stephan F., Saalbach H., Rossi S. (2020). The brain differentially prepares inner and overt speech production: Electrophysiological and vascular evidence. Brain Sci. 10 : 148 . 10.3390/brainsci10030148 [ PMC free article ] [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Tullett A. M., Inzlicht M. (2010). The voice of self-control: Blocking the inner voice increases impulsive responding. Acta Psychol. 135 252–256. 10.1016/j.actpsy.2010.07.008 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Turner M. J., Wood A. G., Barker J. B., Chadha N. (2020). “ Rational self-talk: A rational emotive behaviour therapy (REBT) perspective ,” in Self-talk in sport , eds Latinjak A., Hatzigeorgiadis A. (Abingdon: Routledge; ), 109–122. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Raalte J. L., Brewer B. W., Rivera P. M., Petitpas A. J. (1994). The relationship between observable self-talk and competitive junior tennis players’ match performances. J. Sport Exerc. Psychol. 16 400–415. [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Raalte J. L., Vincent A., Brewer B. W. (2016). Self-talk: Review and sport-specific model. Psychol. Sport Exerc. 22 139–148. 10.1016/j.psychsport.2015.08.004 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Van Raalte J. L., Vincent A., Dickens Y. L., Brewer B. W. (2019). Toward a common language, categorization, and better assessment in self-talk research: Commentary on “Speaking clearly…10 years on. ” Sport Exerc. Perform. Psychol. 8 368–378. 10.1037/spy0000172 [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Verstichel P., Bourak C., Font V., Crochet G. (1997). Langage intérieur après lésion cérébrale gauche: Etude de la représentation phonologique des mots chez des patients aphasiques et non aphasiques [Inner speech following left hemispheric lesion: A study of the phonological representation of words in aphasic and non-aphasic participants]. Neuropsychology 7 281–283. [ Google Scholar ]

- Vygotsky L. S. (1943/1962). Thought and language. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. [ Google Scholar ]

- White R. E., Kuehn M. M., Duckworth A. L., Kross E., Ayduk Ö. (2019). Focusing on the future from afar: Self-distancing from future stressors facilitates adaptive coping. Emotion 19 903–916. 10.1037/emo0000491 [ PubMed ] [ CrossRef ] [ Google Scholar ]

- Winsler A. (2009). “ Still talking to ourselves after all these years: A review of current research on private speech ,” in Private speech, executive functioning, and the development of verbal self-regulation , eds Winsler A., Fernyhough C., Montero I. (New York, NY: Cambridge University Press; ), 3–41. [ Google Scholar ]

Should I Use “I”?

What this handout is about.

This handout is about determining when to use first person pronouns (“I”, “we,” “me,” “us,” “my,” and “our”) and personal experience in academic writing. “First person” and “personal experience” might sound like two ways of saying the same thing, but first person and personal experience can work in very different ways in your writing. You might choose to use “I” but not make any reference to your individual experiences in a particular paper. Or you might include a brief description of an experience that could help illustrate a point you’re making without ever using the word “I.” So whether or not you should use first person and personal experience are really two separate questions, both of which this handout addresses. It also offers some alternatives if you decide that either “I” or personal experience isn’t appropriate for your project. If you’ve decided that you do want to use one of them, this handout offers some ideas about how to do so effectively, because in many cases using one or the other might strengthen your writing.

Expectations about academic writing

Students often arrive at college with strict lists of writing rules in mind. Often these are rather strict lists of absolutes, including rules both stated and unstated:

- Each essay should have exactly five paragraphs.

- Don’t begin a sentence with “and” or “because.”

- Never include personal opinion.

- Never use “I” in essays.

We get these ideas primarily from teachers and other students. Often these ideas are derived from good advice but have been turned into unnecessarily strict rules in our minds. The problem is that overly strict rules about writing can prevent us, as writers, from being flexible enough to learn to adapt to the writing styles of different fields, ranging from the sciences to the humanities, and different kinds of writing projects, ranging from reviews to research.

So when it suits your purpose as a scholar, you will probably need to break some of the old rules, particularly the rules that prohibit first person pronouns and personal experience. Although there are certainly some instructors who think that these rules should be followed (so it is a good idea to ask directly), many instructors in all kinds of fields are finding reason to depart from these rules. Avoiding “I” can lead to awkwardness and vagueness, whereas using it in your writing can improve style and clarity. Using personal experience, when relevant, can add concreteness and even authority to writing that might otherwise be vague and impersonal. Because college writing situations vary widely in terms of stylistic conventions, tone, audience, and purpose, the trick is deciphering the conventions of your writing context and determining how your purpose and audience affect the way you write. The rest of this handout is devoted to strategies for figuring out when to use “I” and personal experience.

Effective uses of “I”:

In many cases, using the first person pronoun can improve your writing, by offering the following benefits:

- Assertiveness: In some cases you might wish to emphasize agency (who is doing what), as for instance if you need to point out how valuable your particular project is to an academic discipline or to claim your unique perspective or argument.

- Clarity: Because trying to avoid the first person can lead to awkward constructions and vagueness, using the first person can improve your writing style.

- Positioning yourself in the essay: In some projects, you need to explain how your research or ideas build on or depart from the work of others, in which case you’ll need to say “I,” “we,” “my,” or “our”; if you wish to claim some kind of authority on the topic, first person may help you do so.

Deciding whether “I” will help your style

Here is an example of how using the first person can make the writing clearer and more assertive:

Original example:

In studying American popular culture of the 1980s, the question of to what degree materialism was a major characteristic of the cultural milieu was explored.

Better example using first person:

In our study of American popular culture of the 1980s, we explored the degree to which materialism characterized the cultural milieu.

The original example sounds less emphatic and direct than the revised version; using “I” allows the writers to avoid the convoluted construction of the original and clarifies who did what.

Here is an example in which alternatives to the first person would be more appropriate:

As I observed the communication styles of first-year Carolina women, I noticed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

Better example:

A study of the communication styles of first-year Carolina women revealed frequent use of non-verbal cues.

In the original example, using the first person grounds the experience heavily in the writer’s subjective, individual perspective, but the writer’s purpose is to describe a phenomenon that is in fact objective or independent of that perspective. Avoiding the first person here creates the desired impression of an observed phenomenon that could be reproduced and also creates a stronger, clearer statement.

Here’s another example in which an alternative to first person works better:

As I was reading this study of medieval village life, I noticed that social class tended to be clearly defined.

This study of medieval village life reveals that social class tended to be clearly defined.

Although you may run across instructors who find the casual style of the original example refreshing, they are probably rare. The revised version sounds more academic and renders the statement more assertive and direct.

Here’s a final example:

I think that Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases, or at least it seems that way to me.

Better example

Aristotle’s ethical arguments are logical and readily applicable to contemporary cases.

In this example, there is no real need to announce that that statement about Aristotle is your thought; this is your paper, so readers will assume that the ideas in it are yours.

Determining whether to use “I” according to the conventions of the academic field

Which fields allow “I”?

The rules for this are changing, so it’s always best to ask your instructor if you’re not sure about using first person. But here are some general guidelines.

Sciences: In the past, scientific writers avoided the use of “I” because scientists often view the first person as interfering with the impression of objectivity and impersonality they are seeking to create. But conventions seem to be changing in some cases—for instance, when a scientific writer is describing a project she is working on or positioning that project within the existing research on the topic. Check with your science instructor to find out whether it’s o.k. to use “I” in their class.

Social Sciences: Some social scientists try to avoid “I” for the same reasons that other scientists do. But first person is becoming more commonly accepted, especially when the writer is describing their project or perspective.

Humanities: Ask your instructor whether you should use “I.” The purpose of writing in the humanities is generally to offer your own analysis of language, ideas, or a work of art. Writers in these fields tend to value assertiveness and to emphasize agency (who’s doing what), so the first person is often—but not always—appropriate. Sometimes writers use the first person in a less effective way, preceding an assertion with “I think,” “I feel,” or “I believe” as if such a phrase could replace a real defense of an argument. While your audience is generally interested in your perspective in the humanities fields, readers do expect you to fully argue, support, and illustrate your assertions. Personal belief or opinion is generally not sufficient in itself; you will need evidence of some kind to convince your reader.

Other writing situations: If you’re writing a speech, use of the first and even the second person (“you”) is generally encouraged because these personal pronouns can create a desirable sense of connection between speaker and listener and can contribute to the sense that the speaker is sincere and involved in the issue. If you’re writing a resume, though, avoid the first person; describe your experience, education, and skills without using a personal pronoun (for example, under “Experience” you might write “Volunteered as a peer counselor”).

A note on the second person “you”:

In situations where your intention is to sound conversational and friendly because it suits your purpose, as it does in this handout intended to offer helpful advice, or in a letter or speech, “you” might help to create just the sense of familiarity you’re after. But in most academic writing situations, “you” sounds overly conversational, as for instance in a claim like “when you read the poem ‘The Wasteland,’ you feel a sense of emptiness.” In this case, the “you” sounds overly conversational. The statement would read better as “The poem ‘The Wasteland’ creates a sense of emptiness.” Academic writers almost always use alternatives to the second person pronoun, such as “one,” “the reader,” or “people.”

Personal experience in academic writing

The question of whether personal experience has a place in academic writing depends on context and purpose. In papers that seek to analyze an objective principle or data as in science papers, or in papers for a field that explicitly tries to minimize the effect of the researcher’s presence such as anthropology, personal experience would probably distract from your purpose. But sometimes you might need to explicitly situate your position as researcher in relation to your subject of study. Or if your purpose is to present your individual response to a work of art, to offer examples of how an idea or theory might apply to life, or to use experience as evidence or a demonstration of an abstract principle, personal experience might have a legitimate role to play in your academic writing. Using personal experience effectively usually means keeping it in the service of your argument, as opposed to letting it become an end in itself or take over the paper.

It’s also usually best to keep your real or hypothetical stories brief, but they can strengthen arguments in need of concrete illustrations or even just a little more vitality.

Here are some examples of effective ways to incorporate personal experience in academic writing:

- Anecdotes: In some cases, brief examples of experiences you’ve had or witnessed may serve as useful illustrations of a point you’re arguing or a theory you’re evaluating. For instance, in philosophical arguments, writers often use a real or hypothetical situation to illustrate abstract ideas and principles.

- References to your own experience can explain your interest in an issue or even help to establish your authority on a topic.

- Some specific writing situations, such as application essays, explicitly call for discussion of personal experience.

Here are some suggestions about including personal experience in writing for specific fields:

Philosophy: In philosophical writing, your purpose is generally to reconstruct or evaluate an existing argument, and/or to generate your own. Sometimes, doing this effectively may involve offering a hypothetical example or an illustration. In these cases, you might find that inventing or recounting a scenario that you’ve experienced or witnessed could help demonstrate your point. Personal experience can play a very useful role in your philosophy papers, as long as you always explain to the reader how the experience is related to your argument. (See our handout on writing in philosophy for more information.)

Religion: Religion courses might seem like a place where personal experience would be welcomed. But most religion courses take a cultural, historical, or textual approach, and these generally require objectivity and impersonality. So although you probably have very strong beliefs or powerful experiences in this area that might motivate your interest in the field, they shouldn’t supplant scholarly analysis. But ask your instructor, as it is possible that they are interested in your personal experiences with religion, especially in less formal assignments such as response papers. (See our handout on writing in religious studies for more information.)

Literature, Music, Fine Arts, and Film: Writing projects in these fields can sometimes benefit from the inclusion of personal experience, as long as it isn’t tangential. For instance, your annoyance over your roommate’s habits might not add much to an analysis of “Citizen Kane.” However, if you’re writing about Ridley Scott’s treatment of relationships between women in the movie “Thelma and Louise,” some reference your own observations about these relationships might be relevant if it adds to your analysis of the film. Personal experience can be especially appropriate in a response paper, or in any kind of assignment that asks about your experience of the work as a reader or viewer. Some film and literature scholars are interested in how a film or literary text is received by different audiences, so a discussion of how a particular viewer or reader experiences or identifies with the piece would probably be appropriate. (See our handouts on writing about fiction , art history , and drama for more information.)

Women’s Studies: Women’s Studies classes tend to be taught from a feminist perspective, a perspective which is generally interested in the ways in which individuals experience gender roles. So personal experience can often serve as evidence for your analytical and argumentative papers in this field. This field is also one in which you might be asked to keep a journal, a kind of writing that requires you to apply theoretical concepts to your experiences.

History: If you’re analyzing a historical period or issue, personal experience is less likely to advance your purpose of objectivity. However, some kinds of historical scholarship do involve the exploration of personal histories. So although you might not be referencing your own experience, you might very well be discussing other people’s experiences as illustrations of their historical contexts. (See our handout on writing in history for more information.)

Sciences: Because the primary purpose is to study data and fixed principles in an objective way, personal experience is less likely to have a place in this kind of writing. Often, as in a lab report, your goal is to describe observations in such a way that a reader could duplicate the experiment, so the less extra information, the better. Of course, if you’re working in the social sciences, case studies—accounts of the personal experiences of other people—are a crucial part of your scholarship. (See our handout on writing in the sciences for more information.)

You may reproduce it for non-commercial use if you use the entire handout and attribute the source: The Writing Center, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Make a Gift

Frequently asked questions

Can i write about myself in the third person.

In most contexts, you should use first-person pronouns (e.g., “I,” “me”) to refer to yourself. In some academic writing, the use of the first person is discouraged, and writers are advised to instead refer to themselves in the third person (e.g., as “the researcher”).

This convention is mainly restricted to the sciences, where it’s used to maintain an objective, impersonal tone. But many style guides (such as APA Style ) now advise you to simply use the first person, arguing that this style of writing is misleading and unnatural.

Ask our team

Want to contact us directly? No problem. We are always here for you.

- Email [email protected]

- Start live chat

- Call +1 (510) 822-8066

- WhatsApp +31 20 261 6040

Our team helps students graduate by offering:

- A world-class citation generator

- Plagiarism Checker software powered by Turnitin

- Innovative Citation Checker software

- Professional proofreading services

- Over 300 helpful articles about academic writing, citing sources, plagiarism, and more

Scribbr specializes in editing study-related documents . We proofread:

- PhD dissertations

- Research proposals

- Personal statements

- Admission essays

- Motivation letters

- Reflection papers

- Journal articles

- Capstone projects

Scribbr’s Plagiarism Checker is powered by elements of Turnitin’s Similarity Checker , namely the plagiarism detection software and the Internet Archive and Premium Scholarly Publications content databases .

The add-on AI detector is powered by Scribbr’s proprietary software.

The Scribbr Citation Generator is developed using the open-source Citation Style Language (CSL) project and Frank Bennett’s citeproc-js . It’s the same technology used by dozens of other popular citation tools, including Mendeley and Zotero.

You can find all the citation styles and locales used in the Scribbr Citation Generator in our publicly accessible repository on Github .

- Affiliate Program

- UNITED STATES

- 台灣 (TAIWAN)

- TÜRKIYE (TURKEY)

- Academic Editing Services

- - Research Paper

- - Journal Manuscript

- - Dissertation

- - College & University Assignments

- Admissions Editing Services

- - Application Essay

- - Personal Statement

- - Recommendation Letter

- - Cover Letter

- - CV/Resume

- Business Editing Services

- - Business Documents

- - Report & Brochure

- - Website & Blog

- Writer Editing Services

- - Script & Screenplay

- Our Editors

- Client Reviews

- Editing & Proofreading Prices

- Wordvice Points

- Partner Discount

- Plagiarism Checker

- APA Citation Generator

- MLA Citation Generator

- Chicago Citation Generator

- Vancouver Citation Generator

- - APA Style

- - MLA Style

- - Chicago Style

- - Vancouver Style

- Writing & Editing Guide

- Academic Resources

- Admissions Resources

Can You Use First-Person Pronouns (I/we) in a Research Paper?

Research writers frequently wonder whether the first person can be used in academic and scientific writing. In truth, for generations, we’ve been discouraged from using “I” and “we” in academic writing simply due to old habits. That’s right—there’s no reason why you can’t use these words! In fact, the academic community used first-person pronouns until the 1920s, when the third person and passive-voice constructions (that is, “boring” writing) were adopted–prominently expressed, for example, in Strunk and White’s classic writing manual “Elements of Style” first published in 1918, that advised writers to place themselves “in the background” and not draw attention to themselves.

In recent decades, however, changing attitudes about the first person in academic writing has led to a paradigm shift, and we have, however, we’ve shifted back to producing active and engaging prose that incorporates the first person.

Can You Use “I” in a Research Paper?

However, “I” and “we” still have some generally accepted pronoun rules writers should follow. For example, the first person is more likely used in the abstract , Introduction section , Discussion section , and Conclusion section of an academic paper while the third person and passive constructions are found in the Methods section and Results section .

In this article, we discuss when you should avoid personal pronouns and when they may enhance your writing.

It’s Okay to Use First-Person Pronouns to:

- clarify meaning by eliminating passive voice constructions;

- establish authority and credibility (e.g., assert ethos, the Aristotelian rhetorical term referring to the personal character);

- express interest in a subject matter (typically found in rapid correspondence);

- establish personal connections with readers, particularly regarding anecdotal or hypothetical situations (common in philosophy, religion, and similar fields, particularly to explore how certain concepts might impact personal life. Additionally, artistic disciplines may also encourage personal perspectives more than other subjects);

- to emphasize or distinguish your perspective while discussing existing literature; and

- to create a conversational tone (rare in academic writing).

The First Person Should Be Avoided When:

- doing so would remove objectivity and give the impression that results or observations are unique to your perspective;

- you wish to maintain an objective tone that would suggest your study minimized biases as best as possible; and

- expressing your thoughts generally (phrases like “I think” are unnecessary because any statement that isn’t cited should be yours).

Usage Examples

The following examples compare the impact of using and avoiding first-person pronouns.

Example 1 (First Person Preferred):

To understand the effects of global warming on coastal regions, changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences and precipitation amounts were examined .

[Note: When a long phrase acts as the subject of a passive-voice construction, the sentence becomes difficult to digest. Additionally, since the author(s) conducted the research, it would be clearer to specifically mention them when discussing the focus of a project.]

We examined changes in sea levels, storm surge occurrences, and precipitation amounts to understand how global warming impacts coastal regions.

[Note: When describing the focus of a research project, authors often replace “we” with phrases such as “this study” or “this paper.” “We,” however, is acceptable in this context, including for scientific disciplines. In fact, papers published the vast majority of scientific journals these days use “we” to establish an active voice. Be careful when using “this study” or “this paper” with verbs that clearly couldn’t have performed the action. For example, “we attempt to demonstrate” works, but “the study attempts to demonstrate” does not; the study is not a person.]

Example 2 (First Person Discouraged):

From the various data points we have received , we observed that higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall have occurred in coastal regions where temperatures have increased by at least 0.9°C.

[Note: Introducing personal pronouns when discussing results raises questions regarding the reproducibility of a study. However, mathematics fields generally tolerate phrases such as “in X example, we see…”]

Coastal regions with temperature increases averaging more than 0.9°C experienced higher frequencies of runoffs from heavy rainfall.

[Note: We removed the passive voice and maintained objectivity and assertiveness by specifically identifying the cause-and-effect elements as the actor and recipient of the main action verb. Additionally, in this version, the results appear independent of any person’s perspective.]

Example 3 (First Person Preferred):

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. The authors confirm this latter finding.

[Note: “Authors” in the last sentence above is unclear. Does the term refer to Jones et al., Miller, or the authors of the current paper?]

In contrast to the study by Jones et al. (2001), which suggests that milk consumption is safe for adults, the Miller study (2005) revealed the potential hazards of ingesting milk. We confirm this latter finding.

[Note: By using “we,” this sentence clarifies the actor and emphasizes the significance of the recent findings reported in this paper. Indeed, “I” and “we” are acceptable in most scientific fields to compare an author’s works with other researchers’ publications. The APA encourages using personal pronouns for this context. The social sciences broaden this scope to allow discussion of personal perspectives, irrespective of comparisons to other literature.]

Other Tips about Using Personal Pronouns

- Avoid starting a sentence with personal pronouns. The beginning of a sentence is a noticeable position that draws readers’ attention. Thus, using personal pronouns as the first one or two words of a sentence will draw unnecessary attention to them (unless, of course, that was your intent).

- Be careful how you define “we.” It should only refer to the authors and never the audience unless your intention is to write a conversational piece rather than a scholarly document! After all, the readers were not involved in analyzing or formulating the conclusions presented in your paper (although, we note that the point of your paper is to persuade readers to reach the same conclusions you did). While this is not a hard-and-fast rule, if you do want to use “we” to refer to a larger class of people, clearly define the term “we” in the sentence. For example, “As researchers, we frequently question…”

- First-person writing is becoming more acceptable under Modern English usage standards; however, the second-person pronoun “you” is still generally unacceptable because it is too casual for academic writing.

- Take all of the above notes with a grain of salt. That is, double-check your institution or target journal’s author guidelines . Some organizations may prohibit the use of personal pronouns.

- As an extra tip, before submission, you should always read through the most recent issues of a journal to get a better sense of the editors’ preferred writing styles and conventions.

Wordvice Resources

For more general advice on how to use active and passive voice in research papers, on how to paraphrase , or for a list of useful phrases for academic writing , head over to the Wordvice Academic Resources pages . And for more professional proofreading services , visit our Academic Editing and P aper Editing Services pages.

Thank you for visiting nature.com. You are using a browser version with limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you use a more up to date browser (or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer). In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

- View all journals

- Explore content

- About the journal

- Publish with us

- Sign up for alerts

- Published: 04 March 2024

How to give great research talks to any audience

- Veronica M. Lamarche ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-2199-6463 1 ,

- Franki Y. H. Kung 2 ,

- Eli J. Finkel ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0002-0213-5318 3 , 4 , 5 na1 ,

- Eranda Jayawickreme ORCID: orcid.org/0000-0001-6544-7004 6 na1 ,

- Aneeta Rattan 7 na1 &

- Thalia Wheatley 8 , 9 na1

Nature Human Behaviour ( 2024 ) Cite this article

3414 Accesses

6 Altmetric

Metrics details

Being able to deliver a persuasive and informative talk is an essential skill for academics, whether speaking to students, experts, grant funders or the public. Yet formal training on how to structure and deliver an effective talk is rare. In this Comment, we give practical tips to help academics to give great talks to a range of different audiences.

This is a preview of subscription content, access via your institution

Access options

Access Nature and 54 other Nature Portfolio journals

Get Nature+, our best-value online-access subscription

24,99 € / 30 days

cancel any time

Subscribe to this journal

Receive 12 digital issues and online access to articles

111,21 € per year

only 9,27 € per issue

Rent or buy this article

Prices vary by article type

Prices may be subject to local taxes which are calculated during checkout

Kirschbaum, C., Pirke, K. M. & Hellhammer, D. H. Neuropsychobiology 28 , 76–81 (1993).

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Gallego, A., McHugh, L., Penttonen, M. & Lappalainen, R. Behav. Modif. 46 , 782–798 (2022).

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Bruner, J. S. Acts of Meaning (Harvard Univ. Press, 1990).

Foy, J. E. Telling Stories: The Art and Science of Storytelling as an Instructional Strategy (eds Brakke, K. & Houska, J. A.) 49–59 (American Psychological Association, 2015).

Anderson, C. TED Talks: The Official TED Guide to Public Speaking: Tips and Tricks for Giving Unforgettable Speeches and Presentations (Hachette UK, 2016).