Graduate Employability: A Review of Conceptual and Empirical Themes

- Published: 29 May 2012

- Volume 25 , pages 407–431, ( 2012 )

Cite this article

- Michael Tomlinson 1

75k Accesses

299 Citations

38 Altmetric

Explore all metrics

The purpose of this paper is to provide an overview of some of the dominant empirical and conceptual themes in the area of graduate employment and employability over the past decade. The paper considers the wider context of higher education (HE) and labour market change, and the policy thinking towards graduate employability. It draws upon various studies to highlight the different labour market perceptions, experiences and outcomes of graduates in the United Kingdom and other national contexts. It further draws upon research that has explored the ways in which students and graduates construct their employability and begin to manage the transition from HE to work. The paper explores some of the conceptual notions that have informed understandings of graduate employability, and argues for a broader understanding of employability than that offered by policymakers.

Similar content being viewed by others

Graduate Employability: A Critical Oversight

Introduction: Rethinking Graduate Employability in Context

Critical perspectives on graduate employability.

Avoid common mistakes on your manuscript.

Introduction

The problem of graduates’ employability remains a continuing policy priority for higher education (HE) policymakers in many advanced western economies. These concerns have been given renewed focus in the current climate of wider labour market uncertainty. Policymakers continue to emphasise the importance of ‘employability skills’ in order for graduates to be fully equipped in meeting the challenges of an increasingly flexible labour market ( DIUS, 2008 ). This paper reviews some of the key empirical and conceptual themes in the area of graduate employability over the past decade in order to make sense of graduate employability as a policy issue. This paper aims to place the issue of graduate employability in the context of the shifting inter-relationship between HE and the labour market, and the changing regulation of graduate employment. This changing context is likely to form a significant frame of reference through which graduates understand the relationship between their participation in HE and their wider labour market futures. Moreover, this may well influence the ways in which they understand and attempt to manage their future ‘employability’. This is further likely to be mediated by national labour market structures in different national settings that differentially regulate the position and status of graduates in the economy.

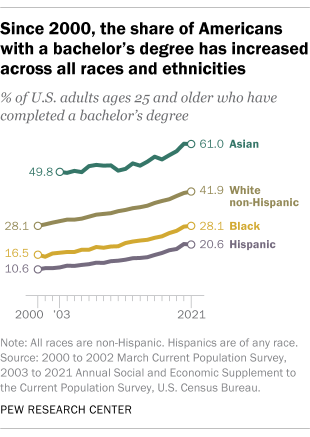

Dominant discourses on graduates’ employability have tended to centre on the economic role of graduates and the capacity of HE to equip them for the labour market. HE systems across the globe are evolving in conjunction with wider structural transformations in advanced, post-industrial capitalism ( Brown and Lauder, 2009 ). Accordingly, there has been considerable government faith in the role of HE in meeting new economic imperatives. Graduates are perceived as potential key players in the drive towards enhancing value-added products and services in an economy demanding stronger skill-sets and advanced technical knowledge. Yet the position of graduates in the economy remains contested and open to a range of competing interpretations. Once characterised as a ‘social elite’ ( Kelsall et al., 1972 ), their status as occupants of an exclusive and well-preserved core of technocratic, professional and managerial jobs has been challenged by structural shifts in both HE and the economy. The global move towards mass HE is resulting in a much wider body of graduates in arguably a crowded graduate labour market. This is further raising concerns around the distribution and equity of graduates’ economic opportunities, as well as the traditional role of HE credentials in facilitating access to desired forms of employment ( Scott, 2005 ).

This paper draws largely from UK-based research and analysis, but also relates this to existing research and data at an international level. It first relates the theme of graduate employability to the changing dynamic in the relationship between HE and the labour market, and the changing role of HE in regulating graduate-level work. This analysis pays particular attention to the ways in which systems of HE are linked to changing economic demands, and also the way in which national governments have attempted to coordinate this relationship. A common theme has been state-led attempts to increasingly tighten the relationship and attune HE more closely to the economy, which itself is set within wider discourse around economic change. It will further show that while common trends are evident across national context, the HE–labour market relationship is also subject to national variability.

The paper then explores research on graduates’ labour market returns and outcomes, and the way they are positioned in the labour market, again highlighting the national variability to graduates’ labour market outcomes. This is then linked to research that has examined the way in which students and graduates are managing the transition into the labour market. This relates largely to the ways in which they approach the job market and begin to construct and manage their individual employability, mediated largely through the types of work-related dispositions and identities that they are developing. Throughout, the paper explores some of the dominant conceptual themes informing discussion and research on graduate employability, in particular human capital, skills, social reproduction, positional conflict and identity.

HE and the Labour Market: A Gradual Decoupling

The inter-relationship between HE and the labour market has been considerably reshaped over time. This has been driven mainly by a number of key structural changes both to higher education institutions (HEIs) and in the nature of the economy. The most discernable changes in HE have been its gradual massification over the past three decades and, in more recent times, the move towards greater individual expenditure towards HE in the form of student fees. In the United Kingdom, for example, state commitment to public financing of HE has declined; although paradoxically, state continues to exert pressures on the system to enhance its outputs, quality and overall market responsiveness ( DFE, 2010 ). Such changes have coincided with what has typically been seen as a shift towards a more flexible, post-industrialised knowledge-driven economy that places increasing demands on the workforce and necessitates new forms of work-related skills ( Hassard et al., 2008 ). The more recent policy in the United Kingdom towards raising fee levels has coincided with an economic downturn, generating concerns over the value and returns of a university degree. Questions continued to be posed over the specific role of HE in regulating skilled labour, and the overall matching of the supply of graduates leaving HE to their actual economic demand and utility ( Bowers-Brown and Harvey, 2004 ).

The relationship between HE and the labour market has traditionally been a closely corresponding one, although in sometimes loose and intangible ways ( Brennan et al., 1996 ; Johnston, 2003 ). HE has traditionally helped regulate the flow of skilled, professional and managerial workers. Furthermore, this relationship was marked by a relatively stable flow of highly qualified young people into well-paid and rewarding employment. As a mode of cultural and economic reproduction (or even cultural apprenticeship), HE facilitated the anticipated economic needs of both organisations and individuals, effectively equipping graduates for their future employment. Thus, HE has been traditionally viewed as providing a positive platform from which graduates could integrate successfully into economic life, as well as servicing the economy effectively.

The correspondence between HE and the labour market rests largely around three main dimensions: (i) in terms of the knowledge and skills that HE transfers to graduates and which then feeds back into the labour market, (ii) the legitimatisation of credentials that serve as signifiers to employers and enable them to ‘screen’ prospective future employees and (iii) the enrichment of personal and cultural attributes, or what might be seen as ‘personality’. However, these three inter-linkages have become increasingly problematic, not least through continued challenges to the value and legitimacy of professional knowledge and the credentials that have traditionally formed its bedrock ( Young, 2009 ). A more specific set of issues have arisen concerning the types of individuals organisations want to recruit, and the extent to which HEIs can serve to produce them.

Traditionally, linkages between the knowledge and skills produced through universities and those necessitated by employers have tended to be quite flexible and open-ended. While some graduates have acquired and drawn upon specialised skill-sets, many have undertaken employment pathways that are only tangential to what they have studied. As Little and Archer (2010) argue, the relative looseness in the relationship between HE and the labour market has traditionally not presented problems for either graduates or employers, particularly in more flexible economies such as the United Kingdom. This may be largely due to the fact that employers have been reasonably responsive to generic academic profiles, providing that graduates fulfil various other technical and job-specific demands.

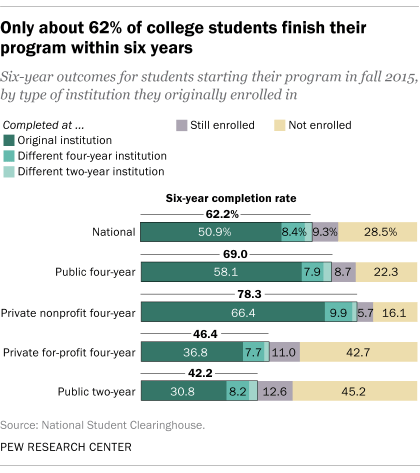

Over time, however, this traditional link between HE and the labour market has been ruptured. The expansion of HE, and the creation of new forms of HEIs and degree provision, has resulted in a more heterogeneous mix of graduates leaving universities ( Scott, 2005 ). This has coincided with the movement towards more flexible labour markets, the overall contraction of management forms of employment, an increasing intensification in global competition for skilled labour and increased state-driven attempts to maximise the outputs of the university system ( Harvey, 2000 ; Brown and Lauder, 2009 ).

Such changes have inevitably led to questions over HE's role in meeting the needs of both the wider labour market and graduates, concerns that have largely emanated from the corporate world ( Morley and Aynsley, 2007 ; Boden and Nedeva, 2010 ). While at one level the correspondence between HE and the labour market has become blurred by these various structural changes, there has also been something of a tightening of the relationship. As Teichler (1999) points out, the increasing alignment of universities to the labour market in part reflects continued pressures to develop forms of innovation that will add value to the economy, be that through research or graduates. Both policymakers and employers have looked to exert a stronger influence on the HE agenda, particularly around its formal provisions, in order to ensure that graduates leaving HE are fit-for-purpose ( Teichler, 1999 , 2007 ; Harvey, 2000 ). Furthermore, HEIs have increasingly become wedded to a range of internal and external market forces, with their activities becoming more attuned to the demands of both employers and the new student ‘consumer’ ( Naidoo and Jamieson, 2005 ; Marginson, 2007 ). Various stakeholders involved in HE — be they policymakers, employers and paying students — all appear to be demanding clear and tangible outcomes in response to increasing economic stakes. A number of tensions and potential contradictions may arise from this, resulting mainly from competing agendas and interpretations over the ultimate purpose of a university education and how its provision should best be arranged.

The changing HE–economy dynamic feeds into a range of further significant issues, not least those relating to equity and access in the labour market. The decline of the established graduate career trajectory has somewhat disrupted the traditional link between HE, graduate credentials and occupational rewards ( Ainley, 1994 ; Brown and Hesketh, 2004 ). However, there are concerns that the shift towards mass HE and, more recently, more whole-scale market-driven reforms may be intensifying class-cultural divisions in both access to specific forms of HE experience and subsequent economic outcomes in the labour market ( Reay et al., 2006 ; Strathdee, 2011 ). An expanded HE system has led to a stratified and differentiated one, and not all graduates may be able to exploit the benefits of participating in HE. Mass HE may therefore be perpetuating the types of structural inequalities it was intended to alleviate. In the United Kingdom, as in other countries, clear differences have been reported on the class-cultural and academic profiles of graduates from different HEIs, along with different rates of graduate return ( Archer et al., 2003 ; Furlong and Cartmel, 2005 ; Power and Whitty, 2006 ). For some graduates, HE continues to be a clear route towards traditional middle-class employment and lifestyle; yet for others it may amount to little more than an opportunity cost.

Perhaps increasingly central to the changing dynamic between HE and the labour market has been the issue of graduate employability. There is much continued debate over the way in which HE can contribute to graduates’ overall employment outcomes or, more sharply, their outputs and value-added in the labour market. What has perhaps been characteristic of more recent policy discourses has been the strong emphasis on harnessing HE's activities to meet changing economic demands. Policy responses have tended to be supply-side focused, emphasising the role of HEIs for better equipping graduates for the challenges of the labour market. For much of the past decade, governments have shown a commitment towards increasing the supply of graduates entering the economy, based on the technocratic principle that economic changes necessitates a more highly educated and flexible workforce ( DFES, 2003 ) This rationale is largely predicated on increased economic demand for higher qualified individuals resulting from occupational changes, and whereby the majority of new job growth areas are at graduate level.

The new UK coalition government, working within a framework of budgetary constraints, have been less committed to expansion and have begun capping student numbers ( HEFCE, 2010 ). They nevertheless remain committed to HE as a key economic driver, although with a new emphasis on further rationalising the system through cutting-back university services, stricter prioritisation of funding allocation and higher levels of student financial contribution towards HE through the lifting of the threshold of university fee contribution ( DFE, 2010 ). There has been perhaps an increasing government realisation that future job growth is likely to be halted for the immediate future, no longer warranting the programme of expansion intended by the previous government.

A further policy response towards graduate employability has been around the enhancement of graduates’ skills, following the influential Dearing Report (1997) . The past decade has witnessed a strong emphasis on ‘employability skills’, with the rationale that universities equip students with the skills demanded by employers. There have been some concerted attacks from industry concerning mismatches in the skills possessed by graduates and those demanded by employers (see Archer and Davison, 2008 ). Universities have typically been charged with failing to instil in graduates the appropriate skills and dispositions that enable them to add value to the labour market. The problem has been largely attributable to universities focusing too rigidly on academically orientated provision and pedagogy, and not enough on applied learning and functional skills.

The past decade in the United Kingdom has therefore seen a strong focus on ‘employability’ skills, including communication, teamworking, ICT and self-management being built into formal curricula. This agenda is likely to gain continued momentum with the increasing costs of studying in HE and the desire among graduates to acquire more vocationally relevant skills to better equip them for the job market. However, while notions of graduate ‘skills’, ‘competencies’ and ‘attributes’ are used inter-changeably, they often convey different things to different people and definitions are not always likely to be shared among employers, university teachers and graduates themselves ( Knight and Yorke, 2004 ; Barrie, 2006 ).

Critically inclined commentators have also gone as far as to argue that the skills agenda is somewhat token and that ‘skills’ built into formal HE curricula are a poor relation to the real and embodied depositions that traditional academic, middle-class graduates have acquired through their education and wider lifestyles ( Ainley, 1994 ). Wider critiques of skills policy ( Wolf, 2007 ) have tended to challenge naive conceptualisations of ‘skills’, bringing into question both their actual relationship to employee practices and the extent to which they are likely to be genuinely ‘demand-led’. Such issues may be compounded by a policy climate of heavy central planning and target-setting around the coordination of skills-based education and training.

In relation to the more specific graduate ‘attributes’ agenda, Barrie (2006) has called for a much more fine-grained conceptualisation of attributes and the potential work-related outcomes they may engender. This should be ultimately responsive to the different ways in which students themselves personally construct such attributes and their integration within, rather than separation from, disciplinary knowledge and practices. Furthermore, as Bridgstock (2009) has highlighted, generic skills discourses often fail to engage with more germane understandings of the actual career-salient skills graduates genuinely need to navigate through early career stages. Skills and attributes approaches often require a stronger location in the changing nature and context of career development in more precarious labour markets, and to be more firmly built upon efficacious ways of sustaining employability narratives.

Graduate employability and debates over the future of work

At another level, changes in the HE and labour market relationship map on to wider debates on the changing nature of employment more generally, and the effects this may have on the highly qualified. Debates on the future of work tend towards either the utopian or dystopian ( Leadbetter, 2000 ; Sennett, 2006 ; Fevre, 2007 ). Perhaps one consensus uniting discussion on the effects of labour market change is that the new ‘knowledge-based’ economy entails significant challenges for individuals, including those who are well educated. Individuals have to flexibly adapt to a job market that places increasing expectation and demands on them; in short, they need to continually maintain their employability . As Clarke (2008) illustrates, the employability discourse reflects the increasing onus on individual employees to continually build up their repositories of knowledge and skills in an era when their career progression is less anchored around single organisations and specific job types. In effect, individuals can no longer rely on their existing educational and labour market profiles for shaping their longer-term career progression.

At one level, there has been an optimistic vision of the economy as being fluid and knowledge-intensive ( Leadbetter, 2000 ), readily absorbing the skills and intellectual capital that graduates possess. The increasingly flexible and skills-rich nature of contemporary employment means that the highly educated are empowered in an economy demanding the creativity and abstract knowledge of those who have graduated from HE. Increasingly, individual graduates are no longer constrained by the old corporate structures that may have traditionally limited their occupational agility. Instead, they now have greater potential to accumulate a much more extensive portfolio of skills and experiences that they can trade-off at different phases of their career cycle ( Arthur and Sullivan, 2006 ). Such notions of economic change tend to be allied to human capital conceptualisations of education and economic growth ( Becker, 1993 ). If individuals are able to capitalise upon their education and training, and adopt relatively flexible and proactive approaches to their working lives, then they will experience favourable labour market returns and conditions. Moreover, they will be more productive, have higher earning potential and be able to access a range of labour market goods including better working conditions, higher status and more fulfilling work.

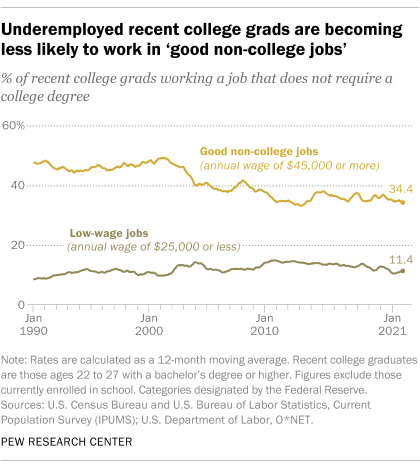

On the other hand, less optimistic perspectives tend to portray contemporary employment as being both more intensive and precarious ( Sennett, 2006 ). The relatively stable and coherent employment narratives that individuals traditionally enjoyed have given way to more fractured and uncertain employment futures brought about by the intensity and inherent precariousness of the new short-term, transactional capitalism ( Strangleman, 2007 ). Rather than being insulated from these new challenges, highly educated graduates are likely to be at the sharp end of the increasing intensification of work, and its associated pressures around continual career management. Consequently, they will have to embark upon increasingly uncertain employment futures, continually having to respond to the changing demands of internal and external labour markets. This may further entail experiencing adverse labour market experiences such as unemployment and underemployment. The challenge for graduate employees is to develop strategies that militate against such likelihoods. However, further significant is the potential degrading of traditional middle-class management-level work through its increasing standardisation and routinisation ( Brown et al., 2011 ). As Brown et al. starkly illustrate, there is growing evidence that old-style scientific management principles are being adapted to the new digital era in the form of a ‘Digital Taylorism’. Moreover, in the context of flexible and competitive globalisation, the highly educated may find themselves forming part of an increasingly disenfranchised new middle class, continually at the mercy of agile, cost-driven flows in skilled labour, and in competition with contemporaries from newly emerging economies.

Critical approaches to labour market change have also tended to point to the structural inequalities within the labour market, reflected and reinforced through the ways in which different social groups approach both the educational and labour market fields. This tends to manifest itself in the form of positional conflict and competition between different groups of graduates competing for highly sought-after forms of employment ( Brown and Hesketh, 2004 ). The expansion of HE and changing economic demands is seen to engender new forms of social conflict and class-related tensions in the pursuit for rewarding and well-paid employment. The neo-Weberian theorising of Collins (2000) has been influential here, particularly in examining the ways in which dominant social groups attempt to monopolise access to desired economic goods, including the best jobs. In light of HE expansion and the declining value of degree-level qualifications, the ever-anxious middle classes have to embark upon new strategies to achieve positional advantages for securing sought-after employment.

Such strategies typically involve the accruement of additional forms of credentials and capitals that can be converted into economic gain. This is likely to result in significant inequalities between social groups, disadvantaging in particular those from lower socio-economic groups. Non-traditional graduates or ‘new recruits’ to the middle classes may be less skilled at reading the changing demands of employers ( Savage, 2003 ; Reay et al., 2006 ). Conversely, traditional middle-class graduates are more able to add value to their credentials and more adept at exploiting their pre-existing levels of cultural capital, social contacts and connections ( Ball, 2003 ; Power and Whitty, 2006 ). Most significantly, they may be better able to demonstrate the appropriate ‘personality package’ increasingly valued in the more elite organisations ( Brown and Hesketh, 2004 ; Brown and Lauder, 2009 ).

The simultaneous decoupling and tightening in the HE–labour market relationship therefore appears to have affected the regulation of graduates into specific labour market positions and their transitions more generally. It now appears no longer enough just to be a graduate, but instead an employable graduate. This may have a strong bearing upon how both graduates and employers socially construct the problem of graduate employability. Thus, a significant feature of research over the past decade has been the ways in which these changes have entered the collective and personal consciousnesses of students and graduates leaving HE. What this has shown is that graduates see the link between participation in HE and future returns to have been disrupted through mass HE. This tends to be reflected in the perception among graduates that, while graduating from HE facilitates access to desired employment, it also increasingly has a limited role ( Tomlinson, 2007 ; Brooks and Everett, 2009 ; Little and Archer, 2010 ). Yet at a time when stakes within the labour market have risen, graduates are likely to demand that this link becomes a more tangible one. These concerns may further feed into students’ approaches to HE more generally, increasingly characterised by more instrumental, consumer-driven and acquisitive learning approaches ( Naidoo and Jamieson, 2005 ). Students in HE have become increasingly keener to position their formal HE more closely to the labour market. With increased individual expenditure, HE has literally become an ‘investment’ and, as such, students may look to it for raising their absolute level of employability.

Students’ and Graduates’ Perceptions and Approaches to Future Employment and Employability

A contested graduate labour market.

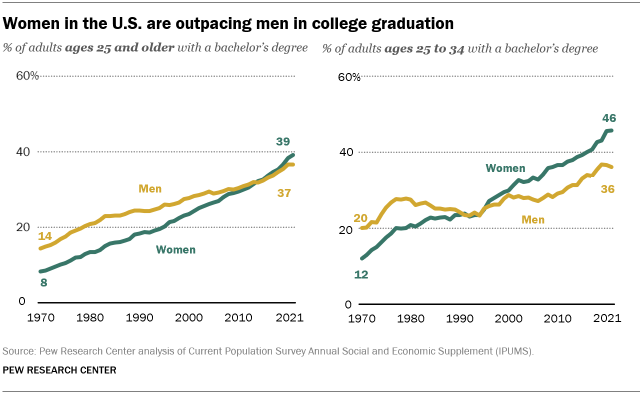

Research has tended to reveal a mixed picture on graduates and their position in the labour market ( Brown and Hesketh, 2004 ; Elias and Purcell, 2004 ; Green and Zhu, 2010 ). More positive accounts of graduates’ labour market outcomes tend to support the notion of HE as a positive investment that leads to favourable returns. Elias and Purcell's (2004) research has reported positive overall labour market outcomes in graduates’ early career trajectories 7 years on from graduation: in the main graduates manage to secure paid employment and enjoy comparatively higher earning than non-graduates. They also reported quite high levels of satisfaction among graduates on their perceived utility of their formal and informal university experiences. Graduates in different occupations were shown to be drawing upon particular graduate skill-sets, be that occupation-specific expertise, managerial decision-making skills, and interactive, communication-based competences. Less positively, their research exposed gender disparities gap in both pay and the types of occupations graduates work within. They found that a much higher proportion of female graduates work within public sector employment compared with males who attained more private sector and IT-based employment. This is further reflected in pay difference and breadth of career opportunities open to different genders. Perhaps significantly, their research shows that graduates occupy a broad range of jobs and occupations, some of which are more closely matched to the archetype of the traditional graduate profession. Graduates clearly follow different employment pathways and embark upon a multifarious range of career routes, all leading to different experiences and outcomes. This is perhaps reflected in the increasing amount of new , modern and niche forms of graduate employment, including graduate sales mangers, marketing and PR officers, and IT executives.

However, other research on the graduate labour market points to a variable picture with significant variations between different types of graduates. Various analysis of graduate returns ( Brown and Hesketh, 2004 ; Green and Zhu, 2010 ) have highlighted the significant disparities that exist among graduates; in particular, some marked differences between the highest graduate earners and the rest. While investment in HE may result in favourable outcomes for some graduates, this is clearly not the case across the board. This is particularly evident among the bottom-earning graduates who, as Green and Zhu show, do not necessarily attain better longer-term earnings than non-graduates. Thus, graduates who are confined to non-graduate occupations, or even new forms of employment that do not necessitate degree-level study, may find themselves struggling to achieve equitable returns. A range of key factors seem to determine graduates’ access to different returns in the labour market that are linked to the specific profile of the graduate.

Research by both Furlong and Cartmel (2005) and Power and Whitty (2006) shows strong evidence of socio-economic influences on graduate returns, with graduates’ relative HE experiences often mediating the link between their origins and their destinations. Power and Whitty's research shows that graduates who experienced more elite earlier forms of education, and then attendance at prestigious universities, tend to occupy high-earning and high-reward occupations. There are two key factors here. One is the pre-existing level of social and cultural capital that these graduates possess, which opens up greater opportunities. The second relates to the biases employers harbour around different graduates from different universities in terms of these universities’ relative so-called reputational capital ( Harvey et al., 1997 ; Brown and Hesketh, 2004 ). It appears that the wider educational profile of the graduate is likely to have a significant bearing on their future labour market outcomes.

Further research has also pointed to experiences of graduate underemployment ( Mason, 2002 ; Chevalier and Lindley, 2009 ).This research has revealed that a growing proportion of graduates are undertaking forms of employment that are not commensurate to their level of education and skills. Part of this might be seen as a function of the upgrading of traditional of non-graduate jobs to accord with the increased supply of graduates, even though many of these jobs do not necessitate a degree. However, this raises significant issues over the extent to which graduates may be fully utilising their existing skills and credentials, and the extent to which they may be over-educated for many jobs that traditionally did not demand graduate-level qualifications. If the occupational structure does not become sufficiently upgraded to accommodate the continued supply of graduates, then mismatches between graduates’ level of education and the demands of their jobs may ensue.

The employability and labour market returns of graduates also appears to have a strong international dimension to it, given that different national economies regulate the relationship between HE and labour market entry differently ( Teichler, 2007 ). The V arieties of Capitalism approach developed by Hall and Soskice (2001) may be useful here in explaining the different ways in which different national economies coordinate the relationship between their education systems and human resource strategies. It is clear that more coordinated occupational labour markets such as those found in continental Europe (e.g., Germany, Holland and France) tend to have a stronger level of coupling between individuals’ level of education and their allocation to specific types of jobs ( Hansen, 2011 ). In such labour market contexts, HE regulates more clearly graduates’ access to particular occupations. This contrasts with more flexible liberal economies such as the United Kingdom, United States and Australia, characterised by more intensive competition, deregulation and lower employment tenure. In effect, market rules dominate. Moreover, in such contexts, there is greater potential for displacement between levels of education and occupational position; in turn, graduates may also perceive a potential mismatch between their qualifications and their returns in the job market.

Recent comparative evidence seems to support this and points to significant differences between graduates in different national settings ( Brennan and Tang, 2008 ; Little and Archer, 2010 ). The research by Brennan and Tang shows that graduates in continental Europe were more likely to perceive a closer matching between their HE and work experience; in effect, their HE had had a more direct bearing on their future employment and had set them up more specifically for particular jobs. Overall, it was shown that UK graduates tend to take more flexible and less predictable routes to their destined employment, with far less in the way of horizontal substitution between their degree studies and target employment. Little and Arthur's research shows similar patterns — among European graduates, there are generally higher levels of graduate satisfaction with HE as a preparation for future employment, as well as much closer matching up between graduates’ credentials and the requirements of jobs. In Europe, it would appear that HE is a more clearly defined agent for pre-work socialisation that more readily channels graduates to specific forms of employment. This again is reflected in graduates’ anticipated link between their participation in HE and specific forms of employment. In some parts of Europe, graduates frame their employability more around the extent to which they can fulfil the specific occupational criteria based on specialist training and knowledge. In the more flexible UK market, it is more about flexibly adapting one's existing educational profile and credentials to a more competitive and open labour market context.

European-wide secondary data also confirms such patterns, as reflected in variable cross-national graduate returns ( Eurostat, 2009 ). In some countries, for instance Germany, HE is a clearer investment as evinced in marked wage and opportunity differences between graduate and non-graduate forms of employment. In countries where training routes are less demarcated (for instance those with mass HE systems), these differences are less pronounced. This is perhaps further reflected in the degree of qualification-based and skills mismatches, often referred to as ‘vertical mismatches’. In flexible labour markets, such as the United Kingdom this remains high. A range of other research has also exposed the variability within and between graduates in different national contexts ( Edvardsson Stiwne and Alves, 2010 ; Puhakka et al., 2010 ). This has illustrated the strong labour market contingency to graduates’ employability and overall labour market outcomes, based largely on how national labour markets coordinate the qualifications and skills of highly qualified labour.

Managing the transition from HE to the labour market

Research done over the past decade has highlighted the increasing pressures anticipated and experienced by graduates seeking well-paid and graduate-level forms of employment. Taken-for-granted assumptions about a ‘job for life’, if ever they existed, appear to have given away to genuine concerns over the anticipated need to be employable . The concerns that have been well documented within the non-graduate youth labour market ( Roberts, 2009 ) are also clearly resonating with the highly qualified. What this research has shown is that graduates anticipate the labour market to engender high risks and uncertainties ( Moreau and Leathwood, 2006 ; Tomlinson, 2007 ) and are managing their expectations accordingly. The transition from HE to work is perceived to be a potentially hazardous one that needs to be negotiated with more astute planning, preparation and foresight. Relatively high levels of personal investment are required to enhance one's employment profile and credentials, and to ensure that a return is made on one's investment in study. Graduates are therefore increasingly likely to see responsibility for future employability as falling quite sharply onto the shoulders of the individual graduate: being a graduate and possessing graduate-level credentials no longer warrants access to sought-after employment, if only because so many other graduates share similar educational and pre-work profiles.

Research done by Brooks and Everett (2008) and Little (2008) indicates that while HE-level study may be perceived by graduates as equipping them for continued learning and providing them with the dispositions and confidence to undertake further learning opportunities, many still perceive a need for continued professional training and development well beyond graduation. This appears to be a response to increased competition and flexibility in the labour market, reflecting an awareness that their longer-term career trajectories are less likely to follow stable or certain pathways. Continued training and lifelong learning is one way of staying fit in a job market context with shifting and ever-increasing employer demands. Discussing graduates’ patterns of work-related learning, Brooks and Everett (2008) argue that for many graduates ‘… this learning was work-related and driven by the need to secure a particular job and progress within one's current position …’ ( Brooks and Everett, 2008 , 71). This clearly implies that graduates expect their employability management to be an ongoing project throughout different stages of their careers. The construction of personal employability does not stop at graduation: graduates appear aware of the need for continued lifelong learning and professional development throughout the different phases of their career progression.

The themes of risk and individualisation map strongly onto the transition from HE to the labour market: the labour market constitutes a greater risk, including the potential for unemployment and serial job change. Individuals therefore need to proactively manage these risks ( Beck and Beck-Gernsheim, 2002 ). Moreover, individual graduates may need to reflexively align themselves to the new challenges of labour market, from which they can make appropriate decisions around their future career development and their general life courses. For Beck and Beck-Germsheim (2002) , processes of ‘institutionalised individualisation’ mean that the labour market effectively becomes a ‘motor’ for individualisation, in that responsibility for economic outcomes is transferred away from work organisations and onto individuals. Research into university graduates’ perceptions of the labour market illustrates that they are increasingly adopting individualised discourses ( Moreau and Leathwood, 2006 ; Tomlinson, 2007 ; Taylor and Pick, 2008 ) around their future employment. Moreau and Leathwood reported strong tendencies for graduates to attribute their labour market outcomes and success towards personal attributes and ‘qualities’ as much as the structure of available opportunities. This is also the case for working-class students who were prone to pathologise their inability to secure employment, even though their outcomes are likely reflect structural inequalities. Tomlinson's research also highlighted the propensity towards discourses of self-responsibilisation by students making the transitions to work. While they were aware of potential structural barriers relating to the potentially classed and gendered nature of labour markets, many of these young people saw the need to take proactive measures to negotiate theses challenges. The problem of managing one's future employability is therefore seen largely as being ‘up to’ the individual graduate.

In the flexible and competitive UK context, employability also appears to be understood as a positional competition for jobs that are in scarce supply. Such perceptions are likely to be reinforced by not only the increasingly flexible labour market that graduates are entering, but also the highly differentiated system of mass HE in the United Kingdom. For graduates, the inflation of HE qualifications has resulted in a gradual downturn in their value: UK graduates are aware of competing in relative terms for sought-after jobs, and with increasing employer demands. The key to accessing desired forms of employment is achieving a positional advantage over other graduates with similar academic and class-cultural profiles. This has some significant implications for the ways in which they understand their employability and the types of credentials and forms of capital around which this is built.

Brown and Hesketh's (2004) research has clearly shown the competitive pressures experienced by graduates in pursuit of tough-entry and sought-after employment, and some of the measures they take to meet the anticipated recruitment criteria of employers. For graduates, the challenge is being able to package their employability in the form of a dynamic narrative that captures their wider achievements, and which conveys the appropriate personal and social credentials desired by employers. Ideally, graduates would be able to possess both the hard currencies in the form of traditional academic qualifications together with soft currencies in the form of cultural and interpersonal qualities. The traditional human and cultural capital that employers have always demanded now constitutes only part of graduates’ employability narratives. Increasingly, graduates’ employability needs to be embodied through their so-called personal capital , entailing the integration of academic abilities with personal, interpersonal and behavioural attributes. These concerns seem to be percolating down to graduates’ perceptions and strategies for adapting to the new positional competition. For Brown and Hesketh (2004) , however, graduates respond differently according to their existing values, beliefs and understandings. ‘Players’ are adept at responding to such competition, embarking upon strategies that will enable them to acquire and present the types of employability narratives that employers demand. ‘Purists’, believing that their employability is largely constitutive of their meritocratic achievements, still largely equate their employability with traditional hard currencies, and are therefore not so adept at responding to signals from employers.

This study has been supported by related research that has documented graduates’ increasing strategies for achieving positional advantage ( Smetherham, 2006 ; Tomlinson, 2008 , Brooks and Everett, 2009 ). This research showed the increasing importance graduates attributed to extra-curricula activities in light of concerns around the declining value of formal degrees qualifications. Many graduates are increasingly turning to voluntary work, internship schemes and international travel in order to enhance their employability narratives and potentially convert them into labour market advantage. Much of this is driven by a concern to ‘stand apart’ from the wider graduate crowd and to add value to their existing graduate credentials. Even those students with strong intrinsic orientations around extra-curricula activities are aware of the need to translate these into marketable, value-added skills. It was not uncommon for students participating, for example, in voluntary or community work to couch these activities in terms of developing teamworking and potential leadership skills. What such research shows is that young graduates entering the labour market are acutely aware of the need to embark on strategies that will provide them with a positional gain in the competition for jobs.

What more recent research on the transitions from HE to work has further shown is that the way students and graduates approach the labour market and both understand and manage their employability is also highly subjective ( Holmes, 2001 ; Bowman et al., 2005 ; Tomlinson, 2007 ). How employable a graduate is, or perceives themselves to be, is derived largely from their self-perception of themselves as a future employee and the types of work-related dispositions they are developing. This is likely to be carried through into the labour market and further mediated by graduates’ ongoing experiences and interactions post-university. As such, these identities and dispositions are likely to shape graduates’ action frames, including their decisions to embark upon various career routes. If initial identities are affirmed during the early stages of graduates’ working lives, they may well ossify and set the direction for future orientations and outlooks. Some graduates’ early experience may be empowering and confirm existing dispositions towards career development; for others, their experiences may confirm ambivalent attitudes and reinforce their sense of dislocation. Research on the more subjective, identity-based aspects of graduate employability also shows that graduates’ dispositions tend to derive from wider aspects of their educational and cultural biographies, and that these exercise some substantial influence on their propensities towards future employment.

Research by Tomlinson (2007) has shown that some students on the point of transiting to employment are significantly more orientated towards the labour market than others. This research highlighted that some had developed stronger identities and forms of identification with the labour market and specific future pathways. Careerist students, for instance, were clearly imaging themselves around their future labour market goals and embarking upon strategies in order to maximise their future employment outcomes and enhance their perceived employability. For such students, future careers were potentially a significant source of personal meaning, providing a platform from which they could find fulfilment, self-expression and a credible adult identity. For other students, careers were far more tangential to their personal goals and lifestyles, and were not something they were prepared to make strong levels of personal and emotional investment towards. The different orientations students are developing appear to be derived from emerging identities and self-perceptions as future employees, as well as from wider biographical dimensions of the student. Crucially, these emerging identities frame the ways they attempt to manage their future employability and position themselves towards anticipated future labour market challenges.

Bowman et al.'s (2005) research showed similar patterns among UK Masters students who, as delayed entrants to the labour market and investors in further human capital, possess a range of different approaches to their future career progression. Their findings relate to earlier work on Careership ( Hodkinson and Sparkes, 1997 ), itself influenced by Bourdieu's (1977) theories of capital and habitus. What their research illustrates is that these graduates’ labour market choices are very much wedded to their pre-existing dispositions and learner identities that frame what is perceived to be appropriate and available. Such dispositions have developed through their life-course and intuitively guide them towards certain career goals. Career choices tend to be made within specific action frames, or what they refer to as ‘horizons for actions’. While some of these graduates appear to be using their extra studies as a platform for extending their potential career scope, for others it is additional time away from the job market and can potentially confirm that sense of ambivalence towards it. Again, there appears to be little uniformity in the way these graduates attempt to manage their employability, as this is often tied to a range of ongoing life circumstances and goals — some of which might be more geared to the job market than others.

Longitudinal research on graduates’ transitions to the labour market ( Holden and Hamblett, 2007 ; Nabi et al., 2010 ) also illustrates that graduates’ initial experiences of the labour market can confirm or disrupt emerging work-related identities. This tends to be mediated by a range of contextual variables in the labour market, not least graduates’ relations with significant others in the field and the specific dynamics inhered in different forms of employment. For graduates, the process of realising labour market goals, of becoming a legitimate and valued employee, is a continual negotiation and involves continual identity work. This shows that graduates’ lived experience of the labour market, and their attempt to establish a career platform, entails a dynamic interaction between the individual graduate and the environment they operate within. This may well confirm emerging perceptions of their own career progression and what they need to do to enhance it. Much of this is likely to rest on graduates’ overall staying power, self-efficacy and tolerance to potentially destabilising experiences, be that as entrepreneurs, managers or researchers. Similar to Holmes’ (2001) work, such research illustrates that graduates’ career progression rests on the extent to which they can achieve affirmed and legitimated identities within their working lives.

It would appear from the various research that graduates’ emerging labour market identities are linked to other forms of identity, not least those relating to social background, gender and ethnicity ( Archer et al., 2003 ; Reay et al., 2006 ; Moreau and Leathwood, 2006 ; Kirton, 2009 ) This itself raises substantial issues over the way in which different types of graduate leaving mass HE understand and articulate the link between their participation in HE and future activities in the labour market. What such research has shown is that the wider cultural features of graduates frame their self-perceptions, and which can then be reinforced through their interactions within the wider employment context.

In terms of social class influences on graduate labour market orientations, this is likely to work in both intuitive and reflexive ways. Studies of non-traditional students show that while they make ‘natural’, intuitive choices based on the logics of their class background, they are also highly conscious that the labour market entails sets of middle-class values and rules that may potentially alienate them. The research by Archer et al. (2003) and Reay et al. (2006) showed that students’ choices towards studying at particular HEIs are likely to reflect subsequent choices. Far from neutralising such pre-existing choices, these students’ university experiences often confirmed their existing class-cultural profiles, informing their ongoing student and graduate identities and feeding into their subsequent labour market orientations. For instance, non-traditional students who had studied at local institutions may be far more likely to fix their career goals around local labour markets, some of which may afford limited opportunities for career progression.

Similar to the Bowman et al. (2005) study, it appears that some graduates’ ‘horizons for action’ are set within by largely intuitive notions of what is appropriate and available, based on what are likely to be highly subjective opportunity structures. Smart et al. (2009) reported significant awareness among graduates of class inequalities for accessing specific jobs, along with expectations of potential disadvantages through employers’ biases around issues such as appearance, accent and cultural code. In a similar vein, Greenbank (2007) also reported concerns among working-class graduates of perceived deficiencies in the cultural and social capital needed to access specific types of jobs. Such graduates are therefore likely to shy away, or psychologically distance themselves, from what they perceive as particular cultural practices, values and protocols that are at odds with their existing ones.

The subjective mediation of graduates’ employability is likely to have a significant role in how they align themselves and their expectations to the labour market. Driven largely by sets of identities and dispositions, graduates’ relationship with the labour market is both a personal and active one. It appears that students and graduates reflect upon their relationship with the labour market and what they might need to achieve their goals. The extent to which future work forms a significant part of their future life goals is likely to determine how they approach the labour market, as well as their own future employability.

Managing Graduate Employability

Much of the graduate employability focus has been on supply-side responses towards enhancing graduates’ skills for the labour market. Problematising the notion of graduate skill is beyond the scope of this paper, and has been discussed extensively elsewhere ( Holmes, 2001 ; Hinchliffe and Jolly, 2011 ). Needless to say, critics of supply-side and skills-centred approaches have challenged the somewhat simplistic, descriptive and under-contextualised accounts of graduate ‘skills’. Skills formally taught and acquired during university do not necessarily translate into skills utilised in graduate employment. Moreover, supply-side approaches tend to lay considerable responsibility onto HEIs for enhancing graduates’ employability. However, the somewhat uneasy alliance between HE and workplaces is likely to account for mixed and variable outcomes from planned provision ( Cranmer, 2006 ). Well-developed and well-executed employability provisions may not necessarily equate with graduates’ actual labour market experiences and outcomes. This also extends to subject areas where there has been a traditionally closer link between the curricula content and specific job areas ( Wilton, 2008 ; Rae, 2007 ). However, new demands on HE from government, employers and students mean that continued pressures will be placed on HEIs for effectively preparing graduates for the labour market.

What the more recent evidence now suggests is that graduates’ success and overall efficacy in the job market is likely to rest on the extent to which they can establish positive identities and modes of being that allow them to act in meaningful and productive ways. The role of employers and employer organisations in facilitating this, as well as graduates’ learning and professional development, may therefore be paramount. Yet research has raised questions over employers’ overall effectiveness in marshalling graduates’ skills in the labour market ( Brown and Hesketh, 2004 ; Morley and Aynsley, 2007 ).

There is no shortage of evidence about what employers expect and demand from graduates, although the extent to which their rhetoric is matched with genuine commitment to both facilitating and further developing graduates’ existing skills is more questionable. The problem of graduate employability and ‘skills’ may not so much centre on deficits on the part of graduates, but a graduate over-supply that employers find challenging to manage. Employers’ propensities towards recruiting specific ‘types’ of graduates perhaps reflects deep-seated issues stemming from more transactional, cost-led and short-term approaches to developing human resources ( Warhurst, 2008 ). Thus, graduates’ successful integration in the labour market may rest less on the skills they possess before entering it, and more on the extent to which these are utilised and enriched through their actual participation in work settings.

Research has continually highlighted engrained employer biases towards particular graduates, ordinarily those in possession of traditional cultural and academic currencies and from more prestigious HEIs ( Harvey et al., 1997 ; Hesketh, 2000 ). One particular consequence of a massified, differentiated HE is therefore likely to be increased discrimination between different ‘types’ of graduates. Perhaps more positively, there is evidence that employers place value on a wider range of softer skills, including graduates’ values, social awareness and generic intellectuality — dispositions that can be nurtured within HE and further developed in the workplace ( Hinchliffe and Jolly, 2011 ). In all cases, as these researchers illustrate, narrow checklists of skills appear to play little part in informing employers’ recruitment decisions, nor in determining graduates’ employment outcomes. Graduates appear to be valued on a range of broad skills, dispositions and performance-based activities that can be culturally mediated, both in the recruitment process and through the specific contexts of their early working lives.

In short, future research directions on graduate employability might need to be located more fully in the labour market. Indeed, there appears a need for further research on the overall management of graduate careers over the longer-term course of their careers. Future research directions on graduate employability will need to explore the way in which graduates’ employability and career progression is managed both by graduates and employers during the early stages of their careers. This will help further elucidate the ways in which graduates’ employability is played out within the specific context of their working lives, including the various modes of professional development and work-related learning that they are engaged in and the formation of their career profiles.

Conclusions

This review has shown that the problem of graduate employability maps strongly onto the shifting dynamic in the relationship between HE and the labour market. This has tended to challenge some of the traditional ways of understanding graduates and their position in the labour market, not least classical theories of cultural reproduction. These changes have added increasing complexities to graduates’ transition into the labour market, as well as the traditional link between graduation and subsequent labour market reward. This review has highlighted how this shifting dynamic has reshaped the nature of graduates’ transitions into the labour market, as well as the ways in which they begin to make sense of and align themselves towards future labour market demands. Graduate employability is clearly a problem that goes far wider than formal participation in HE, and is heavily bound up in the coordination, regulation and management of graduate employment through the course of graduate’ working lives. Graduates’ increasing propensity towards lifelong learning appears to reflect a realisation that the active management of their employability is a career-wide project that will prevail over their longer-term course of their employment.

The development of mass HE, together with a range of work-related changes, has placed considerably more attention upon the economic value and utility of university graduates. These changes have had a number of effects. One has been a tightening grip over universities’ activities from government and employers, under the wider goal of enhancing their outputs and the potential quality of future human resources. Universities have experienced heightened pressures to respond to an increasing range of internal and external market demands, reframing the perceived value of their activities and practices. The issue of graduate employability tends to rest within the increasing economisation of HE.

The review has also highlighted the contested terrain around which debates on graduates’ employability and its development take place. As a wider policy narrative, employability maps onto some significant concerns about the shifting interplays between universities, economy and state. Moreover, in terms of how governments and labour markets may attempt to coordinate and regulate the supply of graduates leaving systems of mass HE. As HE's role for regulating future professional talent becomes reshaped, questions prevail over whose responsibility it is for managing graduates’ transitions and employment outcomes: universities, states, employers or individual graduates themselves?

Employability also encompasses significant equity issues. Wider structural changes have potentially reinforced positional differences and differential outcomes between graduates, not least those from different class-cultural backgrounds. While mass HE potentially opens up opportunities for non-traditional graduates, new forms of cultural reproduction and social closure continue to empower some graduates more readily than others ( Scott, 2005 ). Using Bourdieusian concepts of capital and field to outline the changing dynamic between HE and the labour market, Kupfer (2011) highlights the continued preponderance of structural and cultural inequalities through the existence of layered HE and labour market structures, operating in differentiated fields of power and resources. The relative symbolic violence and capital that some institutions transfer onto different graduates may inevitably feed into their identities, shaping their perceived levels of personal or identity capital. Compelling evidence on employers’ approaches to managing graduate talent ( Brown and Hesketh, 2004 ) exposes this situation quite starkly. The challenge, it seems, is for graduates to become adept at reading these signals and reframing both their expectations and behaviours.

While in the main graduates command higher wages and are able to access wider labour market opportunities, the picture is a complex and variable one and reflects marked differences among graduates in their labour market returns and experiences. The evidence suggests that some graduates assume the status of ‘knowledge workers’ more than others, as reflected in the differential range of outcomes and opportunities they experience. Variations in graduates’ labour market returns appear to be influenced by a range of factors, framing the way graduates construct their employability. The differentiated and heterogeneous labour market that graduates enter means that there is likely to be little uniformity in the way students constructs employability, notionally and personally. Moreover, there is evidence of national variations between graduates from different countries, contingent on the modes of capitalism within different countries. This will largely shape how graduates perceive the linkage between their higher educational qualification and their future returns. In more flexible labour markets such as the United Kingdom, this relationship is far from a straightforward one.

Research in the field also points to increasing awareness among graduates around the challenges of future employability. Again, graduates respond to the challenges of increasing flexibility, individualisation and positional competition in different ways. They construct their individual employability in a relative and subjective manner. Moreover, this is likely to shape their orientations towards the labour market, potentially affecting their overall trajectories and outcomes. That graduates’ employability is intimately related to personal identities and frames of reference reflects the socially constructed nature of employability more generally: it entails a negotiated ordering between the graduate and the wider social and economic structures through which they are navigating. These negotiations continue well into graduates’ working lives, as they continue to strive towards establishing credible work identities. Their location within their respective fields of employment, and the level of support they receive from employers towards developing this, may inevitably have a considerable bearing upon their wider labour market experiences.

Ainley, P. (1994) Degrees of Difference, London: Lawrence Washart.

Google Scholar

Archer, L., Hutchens, M. and Ross, A. (eds.) (2003) Higher Education and Social Class: Issues of Exclusion and Inclusion, London: Routledge.

Archer, W. and Davison, J. (2008) Graduate Employability: The View of Employers, London: Council for Industry and Higher Education.

Arthur, M. and Sullivan, S.E. (2006) ‘The evolution of the boundaryless career concept: Examining the physical and psychological mobility’, Journal of Vocational Behavior 69 (1): 19–29.

Article Google Scholar

Ball, S.J. (2003) Class Strategies and the Education Market: The Middle Classes and Social Advantage, London: Routledge.

Book Google Scholar

Barrie, S. (2006) ‘Understanding what we mean by generic attributes of graduates’, Higher Education 51 (2): 215–241.

Beck, U. and Beck-Gernsheim, E. (2002) Individualization, London: Sage.

Becker, G. (1993) Human Capital: Theoretical and Empirical Analysis with Special Reference to Education (3rd edn), Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Boden, R. and Nedeva, M. (2010) ‘Employing discourse: Universities and graduate “employability”’, Journal of Education Policy 25 (1): 37–54.

Bourdieu, P. (1977) Outline of a Theory of Practice, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bowers-Brown, T. and Harvey, L. (2004) ‘Are there too many graduates in the UK?’ Industry and Higher Education 18 (4): 243–254.

Bowman, H., Colley, H. and Hodkinson, P. (2005) Employability and Career Progression of Fulltime UK Masters Students: Final Report for the Higher Education Careers Services Unit, Leeds: Lifelong Learning Institute.

Brennan, J., Kogan, M. and Teichler, U. (1996) Higher Education and Work, London: Jessica Kingsley.

Brennan, J. and Tang, W. (2008) ‘The Employment of UK Graduates: A Comparison with Europe’, London: The Open University. Report to HEFCE by the Centre for Higher Education Research and Information.

Bridgstock, R. (2009) ‘The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: Enhancing graduate employability through career management skills’, Higher Education Research and Development 28 (1): 31–44.

Brooks, R. and Everett, G. (2008) ‘The predominance of work-based training in young graduates’ learning’, Journal of Education and Work 21 (1): 61–73.

Brooks, R. and Everett, G. (2009) ‘Post-graduate reflections on the value of a degree’, British Educational Research Journal 35 (3): 333–349.

Brown, P. and Hesketh, A.J. (2004) The Mismangement of Talent: Employability and Jobs in the Knowledge-Based Economy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Brown, P. and Lauder, H. (2009) ‘Economic Globalisation, Skill Formation and The Consequences for Higher Education’, in S. Ball, M. Apple and L. Gandin (eds.) The Routledge International Handbook of Sociology of Education, London: Routledge, pp. 229–240.

Brown, P., Lauder, H. and Ashton, D.N. (2011) The Global Auction: The Broken Promises of Education, Jobs and Incomes, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Chevalier, A. and Lindley, J. (2009) ‘Over-education and the skills of UK graduates’, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society 172 (2): 307–337.

Clarke, M. (2008) ‘Understanding and managing employability in changing career contexts’, Journal of European Industrial Training 32 (4): 258–284.

Collins, R. (2000) ‘Comparative and Historical Patterns of Education’, in M. Hallinan (ed.) Handbook of the Sociology of Education, New York: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 213–240.

Cranmer, S. (2006) ‘Enhancing graduate employability: Best intentions and mixed outcome’, Studies in Higher Education 31 (2): 169–184.

Dearing, R. (1997) The Dearing Report: Report for the National Committee of Inquiry into Higher Education: Higher Education in the Learning Society, London: HMSO.

Department for Business Innovation and Skills (DIUS). (2008) Higher Education at Work — High Skills: High Value, London: HMSO.

Department for Education (DFE). (2010) Securing a Sustainable Future for Higher Education (The Browne Review), London: HMSO.

Department for Education Skills (DFES). (2003) The Future of Higher Education, London: HMSO.

Edvardsson Stiwne, E. and Alves, M.G. (2010) ‘Education and the employability of graduates: Will Bologna make a difference?’ European Educational Research Journal 9 (1): 32–44.

Elias, P. and Purcell, K. (2004) The Earnings of Graduates in Their Early Careers: Researching Graduates Seven Years on. Research Paper 1, University of West England & Warwick University, Warwick Institute for Employment Research.

Eurostat. (2009) The Bologna Process in Higher Education in Europe: Key Indicators on the Social Dimension and Mobility, Luxembourg: Office for Official Publications of the European Communities.

Fevre, R. (2007) ‘Employment insecurity and social theory: The power of nightmares’, Work, Employment and Society 21 (3): 517–535.

Furlong, A. and Cartmel, F. (2005) Graduates from Disadvantaged Backgrounds: Early Labour Market Experiences, York: Joseph Rowntree Foundation.

Green, F. and Zhu, Y. (2010) ‘Overqualifcation, job satisfaction, and increasing dispersion in the returns to graduate education’, Oxford Economic Papers 62 (4): 740–763.

Greenbank, P. (2007) ‘Higher education and the graduate labour market: The “Class Factor”’, Tertiary Education and Management 13 (4): 365–376.

Hall, P.A. and Soskice, D.W. (2001) Varieties of Capitalism: The Institutional Foundations of Comparative Advantage, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hansen, H. (2011) ‘Rethinking certification theory and the educational development of the United States and Germany’, Research in Social Stratification and Mobility 29: 31–55.

Harvey, L. (2000) ‘New realities: The relationship between higher education and employment’, Tertiary Education and Management 6 (1): 3–17.

Harvey, L., Moon, S. and Geall, V. (1997) Graduates’ Work: Organisational Change and Students’ Attributes, Birmingham: QHE.

Hassard, J., McCann, L. and Morris, J.L. (2008) Managing in the New Economy: Restructuring White-Collar Work in the USA, UK and Japan, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hesketh, A.J. (2000) ‘Recruiting a graduate elite? Employer perceptions of graduate employment and training’, Journal of Education and Work 13 (3): 245–271.

Higher Education Funding Council for England (HEFCE). (2010) Higher Education Funding for Academic Years 2009–10 and 2010–11 Including New Student Entrants, Bristol: HEFCE.

Hinchliffe, G. and Jolly, A. (2011) ‘Graduate identity and employability’, British Educational Research Journal 37 (4): 563–584.

Hodkinson, P. and Sparkes, A.C. (1997) ‘Careership: A sociological theory of career decision-making’, British Journal of Sociology of Education 18 (1): 29–44.

Holden, R. and Hamblett, J. (2007) ‘The transition from higher education into work: Tales of cohesion and fragmentation’, Education + Training 49 (7): 516–585.

Holmes, L. (2001) ‘Graduate employability: The graduate identity approach’, Quality in Higher Education 7 (1): 111–119.

Johnston, B. (2003) ‘The shape of research in the field of higher education and graduate employment: Some issues’, Studies in Higher Education 28 (4): 413–426.

Kelsall, R.K., Poole, A. and Kuhn, A. (1972) Graduates: The Sociology of an Elite, London: Methuen.

Kirton, G. (2009) ‘Career plans and aspirations of recent black and minority ethnic business graduates’, Work, Employment and Society 23 (1): 12–29.

Knight, P. and Yorke, M. (2004) Learning, Curriculum and Employability in Higher Education, London: Routledge Falmer.

Kupfer, A. (2011) ‘Towards a theoretical framework for the comparative understanding of globalisation, higher education, the labour market and inequality’, Journal of Education and Work 24 (1): 185–207.

Leadbetter, C. (2000) Living on Thin Air, London: Penguin.

Little, B. (2008) ‘Graduate development in European employment: Issues and contradictions’, Education and Training 50 (5): 379–390.

Little, B. and Archer, L. (2010) ‘Less time to study, less well prepared for work, yet satisfied with higher education: A UK perspective on links between higher education and the labour market’, Journal of Education and Work 23 (3): 275–296.

Marginson, S. (2007) ‘University mission and identity for a post-public era’, Higher Education Research and Development 26 (1): 117–131.

Mason, G. (2002) ‘High skills utilisation under mass higher education: Graduate employment in the service industries in Britain’, Journal of Education and Work 14 (4): 427–456.

Moreau, M.P. and Leathwood, C. (2006) ‘Graduates’ employment and discourse of employability: A critical analysis’, Journal of Education and Work 18 (4): 305–324.

Morley, L. and Aynsley, S. (2007) ‘Employers, quality and standards in higher education: Shared values and vocabularies or elitism and inequalities?’ Higher Education Quarterly 61 (3): 229–249.

Nabi, G., Holden, R. and Walmsley, A. (2010) ‘From student to entrepreneur: Towards a model of entrepreneurial career-making’, Journal of Education and Work 23 (5): 389–415.

Naidoo, R. and Jamieson, I. (2005) ‘Empowering participants or corroding learning: Towards a research agenda on the impact of student consumerism in higher education’, Journal of Education Policy 20 (3): 267–281.

Power, S. and Whitty, G. (2006) ‘Graduating and Graduations Within the Middle Class: The Legacy of an Elite Higher Education’, Cardiff: Cardiff University, School of Social Sciences. Cardiff School of Social Sciences Working Paper 118.

Puhakka, A., Rautopuro, J. and Tuominen, V. (2010) ‘Employability and Finnish university graduates’, European Educational Research Journal 9 (1): 45–55.

Rae, D. (2007) ‘Connecting enterprise and graduate employability: Challenges to the higher education curriculum and culture’, Education + Training 49 (8/9): 605–619.

Reay, D., Ball, S.J. and David, M. (2006) Degree of Choice: Class, Gender and Race in Higher Education, Stoke: Trentham Books.

Roberts, K. (2009) ‘Opportunity structures then and now’, Journal of Education and Work 22 (5): 355–368.

Savage, M. (2003) ‘A new class paradigm?’ British Journal of Sociology of Education 24 (4): 535–541.

Sennett, R. (2006) The Culture of New Capitalism, Yale: Yale University Press.

Scott, P. (2005) ‘Universities and the knowledge economy’, Minerva 43 (3): 297–309.

Smart, S., Hutchings, M., Maylor, U., Mendick, H. and Menter, I. (2009) ‘Processes of middle-class reproduction in a graduate employment scheme’, Journal of Education and Work 22 (1): 35–53.

Smetherham, C. (2006) ‘The labour market perceptions of high achieving UK graduates: The role of the first class credential’, Higher Education Policy 19 (4): 463–477.

Strangleman, T. (2007) ‘The nostalgia for the permanence of work? The end of work and its commentators’, The Sociological Review 55 (1): 81–103.

Strathdee, R. (2011) ‘Educational reform, inequality and the structure of higher education in New Zealand’, Journal of Education and Work 24 (1): 27–49.

Taylor, J. and Pick, D. (2008) ‘The work orientations of Australian university students’, Journal of Education and Work 21 (5): 405–421.

Teichler, U. (1999) ‘Higher education policy and the world of work: Changing conditions and challenges’, Higher Education Policy 12 (4): 285–312.

Teichler, U. (2007) ‘Does higher education matter? Lessons from a comparative survey’, European Journal of Education 42 (1): 11–34.

Tomlinson, M. (2007) ‘Graduate employability and student attitudes and orientations to the labour market’, Journal of Education and Work 20 (4): 285–304.

Tomlinson, M. (2008) ‘The degree is not enough: Students’ perceptions of the role of higher education credentials for graduate work and employability’, British Journal of Sociology of Education 29 (1): 49–61.

Warhurst, C. (2008) ‘The knowledge economy, skills and government labour market intervention’, Policy Studies 29 (1): 71–86.

Wilton, N. (2008) ‘Business graduates and management jobs: An employability match made in heaven?’ Journal of Education and Work 21 (2): 143–158.

Wolf, A. (2007) ‘Round and round the houses: The Leitch review of skills’, Local Economy 22 (2): 111–117.

Young, M. (2009) ‘Education, globalisation and the “voice of knowledge”’, Journal of Education and Work 22 (3): 193–204.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

Southampton Education School, University of Southampton, Building 32, Southampton, SO17 1BJ, UK

Michael Tomlinson

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

About this article

Tomlinson, M. Graduate Employability: A Review of Conceptual and Empirical Themes. High Educ Policy 25 , 407–431 (2012). https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2011.26

Download citation

Published : 29 May 2012

Issue Date : 01 December 2012

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2011.26

Share this article

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- graduate employability

- higher education

- degree credentials

- transitions

- Find a journal

- Publish with us

- Track your research

- Share on twitter

- Share on facebook

Employability

The employability agenda corrupts educational and personal values

Knowledge is commodified by the prioritisation of economic imperatives over social and democratic goals in educational policymaking, says Zahid Naz

PowerPoint overuse will be the death of student employability

If slides substitute for note-taking, students will not develop vital skills. Let’s not underestimate their ability to develop them, says Tobiasz Trawiński

Claiming HE only has one humanistic mission won’t reclaim public trust

Most students want universities, first and foremost, to boost employability. Underplaying that purpose will only alienate them, says Samuel Abrams

Lack of communication skills leaves UK graduates naked in the workplace

Universities must address the deficit by offering training in public speaking to all undergraduates regardless of course, says Simon Hall

Universities must transform to ensure no one is left behind in the era of AI

By instilling a passion for innovation and interdisciplinary exploration, higher education can and must remain relevant, say Teruo Fujii and Joseph Aoun

UK universities must do far more to develop skills for an AI-first world

Financial strain shrinks risk appetite, but Kingston is teaching and assessing the skills employers crave as a core part of every subject, says Steven Spier

We can’t stop the ‘rip-off degrees’ debate – but we can change its terms