Engaging in Gender-Based Violence Research: Adopting a Feminist and Participatory Perspective

- First Online: 18 February 2021

Cite this chapter

- Sanne Weber 3 &

- Siân Thomas 3

1276 Accesses

2 Citations

Researching gender-based violence involves different challenges for both participants and researchers, including risks to their mental well-being and physical safety. The possibilities of such research having adverse effects for participants are often stronger in cross-cultural research, since researchers are not always well aware of the locally and culturally specific sensitivities in relation to the issue of gender-based violence. The unequal power relations between researcher and participants, which can exist in all settings, may be exacerbated in contexts of cultural difference. To mitigate these risks and instead attempt to make research a beneficial or even transformative experience for participants, researchers can consider adopting feminist and participatory approaches. After explaining in more detail the risks of gender-based violence research, this chapter describes how feminist and participatory research methods respond to these risks, highlighting particularly the scope for creative approaches to such research.

This is a preview of subscription content, log in via an institution to check access.

Access this chapter

- Available as EPUB and PDF

- Read on any device

- Instant download

- Own it forever

- Compact, lightweight edition

- Dispatched in 3 to 5 business days

- Free shipping worldwide - see info

Tax calculation will be finalised at checkout

Purchases are for personal use only

Institutional subscriptions

True J. The political economy of violence against women. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2012.

Book Google Scholar

Thomas SN, Weber S, Bradbury-Jones C. Using participatory and creative methods to research gender-based violence in the global south and with indigenous communities: findings from a scoping review. Trauma Violence Abuse. 2020.

Google Scholar

Taylor J, Bradbury-Jones C. Sensitive issues in healthcare research: the protection paradox. J Res Nurs. 2011;16(4):303–6.

Article Google Scholar

Malpass A, Sales K, Feder G. Reducing symbolic violence in the research encounter: collaborating with a survivor of domestic abuse in a qualitative study in UK primary care. Sociol Health Illn. 2016;38(3):442–58.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Ponic P, Jategaonkar N. Balancing safety and action: ethical protocols for photovoice research with women who have experienced violence. Arts Health. 2012;4(3):189–202.

Adams V. Metrics: what counts in global health. Durham, NC: Duke University Press; 2016.

Ellsberg M, Heise L, Pena R, Agurto S, Winkvist A. Researching domestic violence against women: methodological and ethical considerations. Stud Fam Plann. 2001;32(1):1–16.

Article CAS PubMed Google Scholar

Merry SE. The seductions of quantification: measuring human rights, gender violence, and sex trafficking. Chicago: University of Chicago Press; 2016.

Ryan L, Golden A. “Tick the box please”: a reflexive approach to doing quantitative social research. Sociology. 2006;40(6):1191–200.

Alhabib S, Nur U, Jones R. Domestic violence against women: systematic review of prevalence studies. J Fam Violence. 2009;25(4):369–82.

Hughes C, Cohen RL. Feminists really do count: the complexity of feminist methodologies. Soc Res Method. 2010;13(3):189–96.

Ellsberg M, Heise L. Researching violence against women: a practical guide for researchers and activists. Washington, DC: World Health Organisation/PATH; 2005.

Hyden M. Narrating sensitive topics. In: Andrews M, Squire C, Tamboukou M, editors. Doing narrative research. London: Sage; 2008. p. 121–36.

Westmarland N, Bows H. Researching gender, violence and abuse: theory, methods, action. Abingdon: Routledge; 2019.

Sikweyiya Y, Jewkes R. Perceptions and experiences of research participants on gender-based violence community based survey: implications for ethical guidelines. PLoS One. 2012;7(4):e35495.

Article CAS PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Hossain M, McAlpine A. Gender-based violence research methodologies in humanitarian settings: an evidence review and recommendations. Cardiff: Elrha; 2017.

McGarry J, Ali P. Researching domestic violence and abuse in healthcare settings: challenges and issues. J Res Nurs. 2016;21(5–6):465–76.

World Health Organization (WHO). Ethical and safety recommendations for intervention research on violence against women. In: Building on lessons from the WHO publication ‘Putting women first: Ethical and safety recommendations for research on domestic violence against women’. Geneva: WHO; 2016.

Ellsberg M, Potts A. Ethical considerations for research and evaluation on ending violence against women and girls: guidance paper prepared by the global Women’s institute (GWI) for the Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Canberra: DFAT; 2018.

Van der Heijden I, Harries J, Abrahams N. Ethical considerations for disability-inclusive gender-based violence research: reflections from a south African qualitative case study. Glob Public Health. 2019;14(5):737–49.

Jewkes R, Wagman J. Generating needed evidence while protecting women research participants in a study of domestic violence in South Africa: a fine balance. In: Lavery JV, Wahl ER, Grady C, Emanuel EJ, editors. Ethical issues in international biomedical research: a case book. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007. p. 350–5.

Skinner T, Hester M, Malos E. Methodology, feminism and gender violence. In: Skinner T, Hester M, Malos E, editors. Researching gender violence: feminist methodology in action. Cullompton: Willan; 2005. p. 1–22.

Judkins-Cohn TM, Kielwasser-Withrow K, Owen M, Ward J. Ethical principles of informed consent: exploring nurses’ dual role of care provider and researcher. J Contin Educ Nurs. 2014;45(1):35–42.

Letherby G. Feminist research in theory and practice. Buckingham: Open University Press; 2003.

Roberts H. Women and their doctors: power and powerlessness in the research process. In: Roberts H, editor. Doing feminist research. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul; 1993. p. 7–29.

Stanley L, Wise S. Breaking out again: feminist ontology and epistemology. 2nd ed. London: Routledge; 1993.

Nagy Hesse-Biber S. Feminist research: exploring, interrogating, and transforming the interconnections of epistemology, methodology and method. In: Nagy Hesse-Biber S, editor. The handbook of feminist research. 2nd ed. Los Angeles: Sage; 2012. p. 2–26.

Chapter Google Scholar

Oliveira E. The personal is political: a feminist reflection on a journey into participatory arts-based research with sex worker migrants in South Africa. Gender Dev. 2019;27(3):523–40.

Jaggar AM. Love and knowledge: emotion in feminist epistemology. Inquiry. 1989;32(2):151–76.

Krystalli R. Narrating violence: feminist dilemmas and approaches. In: Shepherd LJ, editor. Handbook on gender and violence. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar; 2019. p. 173–88.

Haraway DJ. Situated knowledges: the science question in feminism and the privilege of partial perspective. Fem Stud. 1988;14(3):575–99.

hooks, b. Yearning: race, gender, and cultural politics. Boston: South End Press; 1990.

Lorde A. The Master’s tools will never dismantle the Master’s house. In: Sister outsider: essays and speeches. Berkeley: Crossing Press; 2007. p. 110–4.

Tuhiwai Smith L. Decolonizing methodologies. 2nd ed. London: Zed Books; 2012.

Ahmed S. A phenomenology of whiteness. Fem Theory. 2007;8(2):149–68.

Mannell J, Guta A. The ethics of researching intimate partner violence in global health: a case study from global health research. Glob Public Health. 2018;13(8):1035–49.

Nnawulezi N, Lippy C, Serrata J, Rodriguez R. Doing equitable work in inequitable conditions: an introduction to a special issue on transformative research methods in gender-based violence. J Fam Violence. 2018;33:507–13.

Narayan U. Dislocating cultures: identities, traditions, and third world feminism. Abingdon: Routledge; 1997.

Palmary I. “In your experience”: research as gendered cultural translation. Gend Place Cult. 2011;18(1):99–113.

Vara R, Patel N. Working with interpreters in qualitative psychological research: methodological and ethical issues. Qual Res Psychol. 2011;9(1):75–87.

Crenshaw K. Mapping the margins: intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Rev. 1991;43(6):1241–99.

Connell R. Gender, health and theory: conceptualising the issue, in local and world perspective. Soc Sci Med. 2012;74:1675–83.

Lykes MB, Scheib H. The artistry of emancipatory practice: photovoice, creative techniques, and feminist anti-racist participatory action research. In: Bradbury H, editor. The SAGE handbook of action research. 3rd ed. London: Sage; 2017. p. 130–41.

Cornwall A, Jewkes R. What is participatory research? Soc Sci Med. 1995;41(12):1667–76.

Kesby M, Kindon S, Pain R. “Participatory” approaches and diagramming techniques. In: Flowerdew R, Martin D, editors. Methods in human geography. A guide for students doing a research project. 2nd ed. Harlow: Pearson Education; 2005. p. 144–66.

Fals-Borda O. The application of participatory action-research in Latin America. Int Sociol. 1987;2(4):329–47.

Freire P. Pedagogy of the oppressed. 2nd ed. London: Penguin Books; 1996.

Gaventa J, Cornwall A. Power and knowledge. In: Reason P, Bradbury H, editors. The SAGE handbook of action research: participative inquiry and practice. 2nd ed. London: Sage; 2008. p. 172–89.

Wang C, Burris MA. Photovoice: concept, methodology, and use for participatory needs assessment. Health Educ Behav. 1997;24(3):369–87.

Clark T. “We’re over-researched here!”: exploring accounts of research fatigue within qualitative research engagements. Sociology. 2008;42(5):953–70.

Weber S. Participatory visual research with displaced persons: “listening” to post-conflict experiences through the visual. J Refug Stud. 2019;32(3):417–35.

Download references

Author information

Authors and affiliations.

University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Sanne Weber & Siân Thomas

You can also search for this author in PubMed Google Scholar

Corresponding author

Correspondence to Sanne Weber .

Editor information

Editors and affiliations.

Institute of Clinical Sciences, College of Medical and Dental Sciences, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Caroline Bradbury-Jones

Institute of Applied Health Research, University of Birmingham, Birmingham, UK

Louise Isham

Rights and permissions

Reprints and permissions

Copyright information

© 2021 Springer Nature Switzerland AG

About this chapter

Weber, S., Thomas, S. (2021). Engaging in Gender-Based Violence Research: Adopting a Feminist and Participatory Perspective. In: Bradbury-Jones, C., Isham, L. (eds) Understanding Gender-Based Violence. Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65006-3_16

Download citation

DOI : https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-65006-3_16

Published : 18 February 2021

Publisher Name : Springer, Cham

Print ISBN : 978-3-030-65005-6

Online ISBN : 978-3-030-65006-3

eBook Packages : Medicine Medicine (R0)

Share this chapter

Anyone you share the following link with will be able to read this content:

Sorry, a shareable link is not currently available for this article.

Provided by the Springer Nature SharedIt content-sharing initiative

- Publish with us

Policies and ethics

- Find a journal

- Track your research

- Architecture and Design

- Asian and Pacific Studies

- Business and Economics

- Classical and Ancient Near Eastern Studies

- Computer Sciences

- Cultural Studies

- Engineering

- General Interest

- Geosciences

- Industrial Chemistry

- Islamic and Middle Eastern Studies

- Jewish Studies

- Library and Information Science, Book Studies

- Life Sciences

- Linguistics and Semiotics

- Literary Studies

- Materials Sciences

- Mathematics

- Social Sciences

- Sports and Recreation

- Theology and Religion

- Publish your article

- The role of authors

- Promoting your article

- Abstracting & indexing

- Publishing Ethics

- Why publish with De Gruyter

- How to publish with De Gruyter

- Our book series

- Our subject areas

- Your digital product at De Gruyter

- Contribute to our reference works

- Product information

- Tools & resources

- Product Information

- Promotional Materials

- Orders and Inquiries

- FAQ for Library Suppliers and Book Sellers

- Repository Policy

- Free access policy

- Open Access agreements

- Database portals

- For Authors

- Customer service

- People + Culture

- Journal Management

- How to join us

- Working at De Gruyter

- Mission & Vision

- De Gruyter Foundation

- De Gruyter Ebound

- Our Responsibility

- Partner publishers

Your purchase has been completed. Your documents are now available to view.

Researching Gender-Based Violence

Embodied and intersectional approaches.

- Edited by: April D.J. Petillo and Heather R. Hlavka

- X / Twitter

Please login or register with De Gruyter to order this product.

- Language: English

- Publisher: New York University Press

- Copyright year: 2022

- Audience: Professional and scholarly;

- Keywords: Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Method ; Method ; Method ; Intersectionality ; Intersectionality ; Intersectionality ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Introspection ; Body ; Body ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Intersectionality ; Intersectionality ; Intersectionality ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Method ; Method ; Method ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Research ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Intersectionality ; Intersectionality ; Intersectionality ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Method ; Method ; Method ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Standpoint ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Race ; Race ; Poetry ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Black Feminist Methodology ; Care ethics ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Rural ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Mexico ; Victimhood ; Femicide ; Gender-based violence ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Interpersonal ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Power ; Knowledge production ; Knowledge production ; Knowledge Production ; Research ethics ; Research ethics ; Exploitation ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Research ethics ; Research ethics ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Reflexivity ; Latina survivors ; Embodiment ; Embodiment ; Embodiment ; Narrative ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Trafficking ; Agency ; Ethics ; Ethics ; Interviewing ; Colonization ; Arab Gulf ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Knowledge production ; Knowledge production ; Knowledge Production ; State ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Sexual Abuse ; Children ; Knowledge production ; Knowledge production ; Knowledge Production ; Attorneys ; Elite ; Trauma ; Trauma ; Embodiment ; Embodiment ; Embodiment ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Intersectional ; Intersectional ; Ethics ; Ethics ; Body ; Body ; El Salvador ; Movement ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Court ; adjudication ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Feminist ; Race ; Race ; Trauma ; Trauma ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Ethnography ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Embodiment ; Embodiment ; Embodiment ; Intersectional ; Intersectional ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Embodied ; Social justice ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; Violence ; violence

- Published: August 2, 2022

- ISBN: 9781479812219

- Free Associations Podcast

- Quantitative Methods Review and Primer

- Practically Speaking

- Mini-Master of Public Health (MPH)

- Compassionate Leadership

- Teaching Excellence in Public Health

- Climate Change

- Communication

- Data Visualization

- Environmental Health

- Epidemiology

- Health Equity

- Healthcare Management

- Mental Health

- Monitoring and Evaluation

- Research Methods

- Statistical Computing

- Library Expand Navigation

- Custom Expand Navigation

- About Expand Navigation

Stay Informed

Sign up to receive the latest on events, programs, and news.

- Learning Opportunities

- Summer Institute

- Gender-Based Violence: Research Methods and Analysis (SI 18)

Gender-Based Violence: Research Methods and Analysis

Nafisa halim, phd, ma(s) , research assistant professor, global health, busph, monica adhiambo onyango, phd, rn, mph, ms (nursing) , clinical assistant professor, global health, busph, program description.

Gender-based violence affects people around the world every day. This violence, mainly towards women, reinforces power dynamics and impacts overall health, including physical and psychological development.

This program aims to enhance participants’ ability to conduct technically rigorous, ethically-sound, and policy-oriented research on various forms of gender-based violence. Individuals working on and interested in the areas of sexual and reproductive health, maternal and child health, adolescent health, HIV, mental health and substance use will most benefit from taking this program.

The program will cover the following topics:

- Conceptualizing and researching various forms of gender-based violence;

- Developing conceptual frameworks for violence and health research;

- Ethics and safety;

- Survey research on violence and questionnaire design;

- Intervention research: approaches and challenges;

- Qualitative research on violence;

- Violence research in healthcare settings

The program will be taught through a series of interactive lectures, practical exercises, group work and assigned reading.

Competencies

Participants will learn:

- Current gold standard methods to conceptualize and measure gender-based violence;

- Validity and reliability of GBV measures;

- Tool development and validation methods;

- Ethical and safety issues in GBV research;

Intended Audience

Participants interested in investigating gender-based violence as part of a quantitative or qualitative study or an intervention evaluation will find it particularly relevant.

Required knowledge/pre-requisites

Participants are expected have some prior familiarity or experience with conducting research.

Discounts available—visit our FAQs page to learn more.

Low-cost, on-campus housing is also available. Contact us for more information.

The Summer Institute process was very easy and well organized

Nafisa Halim

is a sociologist with expertise in monitoring and evaluation of public health programs. As a PI/Co-I, Halim served on twelve evaluation studies, and conducted a wide range of activities including data processing and analysis; sampling and sample size calculations; database development and management; and study implementation and field training. Halim has consulted with WHO, served on research projects funded by USAID, NIH, the Medical Research Council (South Africa) and private foundations, and partnered with several implementing organizations including Pathfinder, Pact Save the Children, World Education Initiatives, icddr,b. Halim was recognized for her excellence in teaching in 2016.

Monica Adhiambo Onyango

has over 25 years’ experience in health care delivery, teaching and research. Her experience includes Kenya Ministry of Health as a nursing officer in management positions at two hospitals and as a lecturer at the Nairobi’s Kenya Medical Training College, School of Nursing. Dr. Onyango also worked as a health team leader with international non-governmental organizations in relief and development in South Sudan, Angola, and a refugee camp in Kenya. In addition to her teaching engagement, she also takes up consultancies on health care delivery, management and research in relief and development contexts. In 2011, Dr. Onyango co-founded the global nursing caucus, whose mission is to advance the role of nursing in global health practice, education and policy through advocacy, collaboration, engagement, and research.

Program Details

-Monday, 9:00am-4:00pm -Tuesday, 9:00am-4:00pm -Wednesday, 9:00am-3:00pm

- Open access

- Published: 08 December 2023

Participatory approaches and methods in gender equality and gender-based violence research with refugees and internally displaced populations: a scoping review

- Michelle Lokot 1 ,

- Erin Hartman 1 &

- Iram Hashmi 1

Conflict and Health volume 17 , Article number: 58 ( 2023 ) Cite this article

1785 Accesses

1 Citations

13 Altmetric

Metrics details

A Correction to this article was published on 03 January 2024

This article has been updated

Using participatory approaches or methods are often positioned as a strategy to tackle power hierarchies in research. Despite momentum on decolonising aid, humanitarian actors have struggled to describe what ‘participation’ of refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs) means in practice. Efforts to promote refugee and IDP participation can be tokenistic. However, it is not clear if and how these critiques apply to gender-based violence (GBV) and gender equality—topics that often innately include power analysis and seek to tackle inequalities. This scoping review sought to explore how refugee and IDP participation is conceptualised within research on GBV and gender equality. We found that participatory methods and approaches are not always clearly described. We suggest that future research should articulate more clearly what constitutes participation, consider incorporating feminist research methods which have been used outside humanitarian settings, take more intentional steps to engage refugees and IDPs, ensure compensation for their participation, and include more explicit reflection and strategies to address power imbalances.

Introduction

Within research, ‘participation’ has often been understood as the process of directly involving people who are affected by a particular issue, in the process of research [ 1 ]. Humanitarian actors, including international non-governmental organisations (NGOs), UN actors and local NGOs assert the importance of participation of populations affected by crises—refugees and internally displaced persons (IDPs)—in humanitarian activities. The Humanitarian Accountability Partnership’s (HAP) 2013 standard—a key humanitarian guideline—positions participation as vital to humanitarian accountability. HAP defines participation as: ‘listening and responding to feedback from crisis-affected people when planning, implementing, monitoring and evaluating programmes, and making sure that crisis-affected people understand and agree with the proposed humanitarian action and are aware of its implications’ [ 2 ].

The concept of ‘participatory research’ is sometimes used when discussing how to enhance participation in research. Caroline Lenette and colleagues suggest that when talking about participatory research, there is a difference between taking a ‘holistic approach’ within a broader ‘participatory paradigm’ and using methods identified as ‘participatory’ such as PhotoVoice, that is, a difference between methodology (or approach) and method [ 1 ]. In this paper, we use their framing of approach versus method to distinguish between efforts to embed participatory strategies within research holistically, in contrast with using participatory research methods, while also recognising that both of these framings may co-exist within a research project. Examples of taking a holistic approach include ‘community-based participatory research’ (CBPR) and Participatory Action Research (PAR). CBPR has been used to ensure refugees/IDPs are involved at every stage of the research process, and focuses on ensuring that research practices address unequal power hierarchies and adhere to ethical principles [ 3 , 4 ]. PAR also represents a research paradigm/approach focused on working with populations affected by an issue to generate momentum for change. Scholars urge that care is taken with implementing PAR, because of the risk of creating false hope that action will be taken based on the research [ 5 ]. Research may be labelled as using PAR without real meaning: ‘The trend of putting the terms “participatory” and “action” before “research” has led to co-option: not every project labelled PAR is “participatory” research…’ [ 6 ]. Different to this holistic approach, certain research methods are often associated with being participatory, for example PhotoVoice, theatre or arts-based methods. Scholars have observed the ‘glorification’ of arts-based methods, which may be implemented blindly because they are seen as participatory, creative and innovative—without consideration of the relevance of these methods for affected populations [ 7 ].

The concept of participation has become more common within the humanitarian sector as a result of how it has been operationalised within international development, including through the work of practitioners such as Robert Chambers [ 8 ]. In the development sector, participation was a means of shifting power back to communities, for example, through approaches like ‘participatory rural appraisal’ [ 9 ]. Some have critiqued these efforts, labelling them unsuccessful in shifting power dynamics within international development [ 10 ]. Others point to external shifts that have decreased the focus on hearing directly from affected populations, including mandates from donors that development and humanitarian actors deliver impact and value for money [ 11 ]. Despite participation sometimes being connected to improving efficiency [ 12 ], in humanitarian settings the capacity to be participatory is often pitted against the urgency of responding to crises. For example, taking the time to listen to refugees/IDPs is seen as too challenging with the limited funding offered by short-term emergency projects [ 13 ]. There may also be a distinction between listening to refugees/IDPs and actively involving them in design and analysis of research, especially when listening occurs in an extractive way [ 7 ]. Further complicating matters, the term ‘participation’ is sometimes used interchangeably with other terms, such as inclusion, engagement and involvement [ 14 , 15 ]. Outside of international development and humanitarian action, participatory approaches and methods are recognised as holding important potential for shifting power [ 1 , 16 ], transforming knowledge production [ 17 ], increasing equity [ 18 , 19 ], ensuring marginalised populations are reached [ 20 , 21 , 22 ], and enabling innovative research practice and methods [ 21 , 23 , 24 ].

Humanitarian actors have sought to create processes to enhance the participation of refugees and IDPs within humanitarian activities, including research. Research with refugees and IDPs may be conducted by academic or humanitarian actors, and may include baselines, assessments, evaluations and specific research studies. Within such research, efforts to promote participation may include training refugees and IDPs to collect data themselves, consulting them on their needs, and ensuring that they share their perspectives during evaluations. Humanitarian actors invoke the concept of participation to varying degrees: in instrumental ways to achieve better outcomes, and in practical ways such as through their relationships with refugees and IDPs [ 25 ].

Efforts to enhance refugee/IDP participation in research have been criticised for being tokenistic, stemming from the concept of participation being ‘externally imposed’ [ 15 ]. Involvement of refugees within research has been described as ‘exploitative’, whereby refugees are treated as merely sources of data rather than as individuals [ 26 ]. Conflict-affected populations have expressed frustration with being convened for ‘consultations’ when humanitarian actors have already made decisions about their needs and identified solutions [ 27 ]. Humanitarian actors have also been criticised for only promoting women’s participation to improve efficiency [ 9 ] and for failing to recognise how gender, age, ethnicity, economic status and other power hierarchies might constrain participation in humanitarian settings [ 28 ], which increases the influence of power-holders like refugee elites [ 29 ]. These critiques are not necessarily new, but demonstrate there is lack of clarity on what it means for research to reflect ‘refugee voices’ [ 30 ]. Efforts to be ‘participatory’ often lack clarity on what this means [ 31 ].

Critiques of poor implementation of participation have not specifically been applied to gender equality research. Gender equality research—which includes research on gender-based violence (GBV)—often involves consideration of power dynamics, thus often positions participation as a pre-cursor for gender equality [ 9 ]. Participatory research and feminist research share common goals of empowering marginalised populations [ 1 ]. Understanding how participation occurs within research on gender equality may provide important lessons for how participation is being used in research which already uses power as a key lens. For example, while not among refugees and IDPs, recent examples of feminist participatory research with other populations have considerably advanced scholarship through piloting new methods such as body mapping to understand inequity [ 32 ], digital mapping to conceptualise street harassment [ 33 ] and participatory video to provide new insights on gender inequalities [ 34 ]. Feminists have provided critical new insights for participatory research, such as through emphasising not just women’s voices but also their silences during the research process [ 35 ], and reframing ethics from women’s perspective [ 36 ]. Evaluation practice has also been transformed through use of feminist participatory action research approaches that position evaluation participants as co-researchers, challenging the power dynamics often built into evaluation processes [ 37 , 38 ]. Feminist participatory research has provided particular insights for research on violence, including agenda-setting on the use of trauma-informed approaches [ 39 , 40 ], integrating feminist principles into quantitative studies on violence [ 41 ] and using indigenous feminist approaches to reframe women’s safety [ 42 ]. Feminist research approaches and methods continue to push the boundaries of what it means to be ‘participatory’ in diverse settings [ 43 ].

This scoping review explores academic and grey literature on gender equality and GBV among refugees and IDPs which describes itself as ‘participatory’. Specifically, the objectives of this review were to: (1) describe the contexts, approaches and methods used in gender and GBV research with refugees and IDPs; (2) outline the rationale and impacts of promoting refugee/IDP participation in research; (3) describe how refugee/IDP participation is conceptualised, including how participatory approaches and methods are used in research.

We followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR) to conduct and report on this scoping review [ 44 ]. We conducted a scoping review rather than a systematic review to recognise that the body of evidence on refugee/IDP participation in research on gender and GBV is still emerging, and to acknowledge that we must understand how the literature defines participation, what methods are used and what evidence currently exists on the topic. Since we were focused on understanding the concept of participation rather than addressing effectiveness or appropriateness [ 45 ], a scoping review was deemed the best approach. In line with Chang’s approach for scoping reviews [ 46 ], instead of summarising and assessing the quality of evidence, we explored the literature, identified key definitions and themes and identified the type and nature of evidence available.

Search strategy

We searched five academic databases (Medline, PsycINFO, Academic Search Complete, Web of Science and Scopus) in February 2022. The database searches included search terms related to three main concepts: (1) gender equality and GBV, (2) refugees/IDPs, and (3) participation. Table 1 outlines the key search terms used for each database.

We supplemented the academic database search by searching Google and Google Scholar using the following search strings: “refugee participation” AND gender; “refugee participation” AND gender-based violence; refugee AND gender AND participatory research; displaced AND gender AND participatory research. We limited results for Google and Google Scholar to the first 200 hits per search and cleared browsing data after each search. All searches were conducted without signing into Google to prevent tailoring of results by location and search history [ 47 ]. We searched institutional websites of organisations working on gender, GBV and refugee/IDP research, specifically: UNFPA, UN Women, UNHCR, Women’s Refugee Commission and International Center for Research on Women. We also asked practitioners and researchers in this field to send articles that may fulfill inclusion criteria through the Sexual Violence Research Initiative and Forced Migration mailing lists. We hand-searched the reference lists of included papers to identify additional records for inclusion. In order to prevent publication bias and avoid excluding knowledge produced by non-academic actors, we intentionally searched sources outside of academic databases [ 48 ].

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Articles in English from any time period and country involving empirical research with refugees/IDPs on gender equality or GBV were included. We included high-income settings where refugees are resettled like the United States, Australia, European countries and Canada, recognising firstly that there has been considerable investment in participatory research and emerging scholarship on what it means to be ‘participatory’ from these settings; and secondly that the challenges in active conflict and humanitarian settings would likely prevent participatory research from occurring.

Screening occurred in two stages using Covidence. First, we screened titles and abstracts, excluding non-empirical research, studies unrelated to gender equality or GBV and studies that collected data only amongst host populations or amongst practitioners, rather than refugee/IDP populations,were also excluded. During the full-text review, we narrowed our criteria to search full texts for descriptions of efforts to promote participation of refugees/IDPs. Studies that did not incorporate this term or various forms of it (e.g. ‘participatory’ and ‘involvement’) were excluded. Where multiple records by the same author existed for the same research, only the earliest record was included. During the title/abstract screening and full-text review process, all articles were double-screened with regular meetings held between the three researchers to reach consensus. The first author reviewed all articles at both stages. Table 2 outlines the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Data analysis

For each included article, we extracted information on: (a) study design (country, type of population, nationality of refugees/IDPs, sample size, research methods), (b) type of gender equality or GBV issue, and (c) participation (level of focus on participation, definitions of participation, rationale for participatory approach, recommendations for future participatory research, impacts of participation). For population type, we classified based on how the populations were described in the study, rather than using legal definitions of refugees, IDPs, migrants or asylum seekers. We defined ‘gender equality’ using UN Women’s definition as ‘equal rights, responsibilities and opportunities of women and men and girls and boys’ [ 49 ]. We initially classified studies on three levels according to the degree to which the participation was a focus: (1) low: participation in research is mentioned in passing/without further discussion or explanation, (2) medium: participation in research is referenced only in the methods section, or (3) high: participation in research is referenced in the methods section as well as throughout the paper.

Data was extracted using Covidence. Each article was extracted by two authors, with the first author extracting every article. We analysed extracted data to identify: whether and how participation was defined and to what extent it was a focus; the types of methods and strategies used to ensure participation of refugees/IDPs in research; the rationale for promoting participation, including how power dynamics were framed; the impacts of participation; and recommendations for improving participation.

Limitations

Our review has a few limitations. Firstly, due to time and staffing constraints, we only searched for a few key concepts related to participation in academic databases, rather than specifically searching for methods or methodologies commonly identified as participatory. This may have limited the studies that were identified in the database search. Secondly, our review is limited by whatever content authors chose to include in their papers, which may not have been fully representative of the holistic approach taken to participation or to the participatory methods used. Authors may have been constrained by their journal requirements, and may not have been able to include the full level of detail. In at least two cases [ 50 , 51 ], methods sections were shorter because the authors subsequently published a solely methods-focused paper—which fell outside the scope of our review. As with any review, our analysis is confined to what authors describe, which may only be a snapshot of what occurred in their research. Finally, our ranking approach was not a straight-forward process and often required judgments be made about the level of content on participation included by authors. While we made decisions about rankings together, it is possible that the lines between categories are more blurred.

Final sample

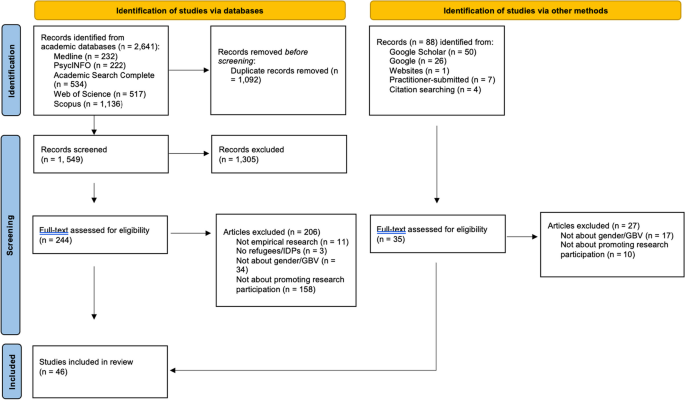

Out of 2641 results from five academic databases, 1092 were duplicates, resulting in 1549 unique records being screened.

Alongside the academic database records, 88 additional records were identified and screened from Google Scholar (n = 50), Google (n = 26), institutional websites (n = 1), practitioners (n = 7) and through hand-searching references from included papers (n = 4). After screening, 35 of these were included in the full-text review and 8 of these were deemed eligible.

We assessed 244 full-text papers from academic databases for eligibility. Of these, 206 studies (84%) were excluded due to not being empirical research (n = 11), not including refugees/IDPs (n = 3), not being about gender/GBV (n = 34), or not mentioning referencing being participatory in approach or using a participatory method (n = 158). Among studies from other sources, 27 studies (77%) were excluded due to not being about gender/GBV (n = 17) or not being about promoting participation (n = 10). In total, 46 studies were included, specifically 38 from academic databases and 8 studies from other sources. Figure 1 outlines the scoping review process at different stages using an adapted PRISMA framework.

Adapted PRISMA framework

Study types and design

Out of the 46 included studies, 39 adopted a qualitative design and the remaining seven employed quantitative (n = 3) and mixed methods (n = 4). The qualitative studies utilized various methods, including semi-structured interviews, focus group discussions (FGD), ‘participatory group discussions’, and participatory mapping and ranking approaches. In total, eight studies used photography as a research method, with three explicitly mentioning using ‘PhotoVoice’ and the rest adopting a participatory and ethnographic photographic approach. Quantitative studies mainly used surveys, whereas mixed method studies employed interviews and FGDs in addition to surveys. Table 3 shows the characteristics of the studies in this review.

Study settings, populations and funders

Included studies were conducted in 29 countries, with the most studies conducted in the United States (n = 8), followed by Australia (n = 7) and Uganda (n = 5). Most studies were conducted in only one country (n = 40) only, while a smaller number were conducted in three countries (n = 2) or two countries (n = 2). One study was conducted in 8 countries and another in 5 countries. According to geographical region, North America (n = 12), Australia/Asia (n = 13) and sub-Saharan Africa (n = 13) were the most (and equally) represented, followed by Europe/Caucuses (n = 12), and the Middle East and North Africa (n = 8). Only two studies were conducted in South America, both in Colombia.

Overall, close to half the studies (n = 21) collected data solely from refugees. A further 17 studies included some combination of refugees with other populations such as IDPs, (n = 2), practitioners (n = 3), practitioners and other stakeholders (n = 2), migrants (n = 1), asylum seekers (n = 3), undocumented migrants and asylum seekers (n = 1), immigrants (n = 3), immigrants and practitioners (n = 1), and IDPs and practitioners (n = 1). In total 6 studies focused solely on IDP populations, while a further 2 focused on IDPs and practitioners (n = 1) and IDPs, practitioners and other stakeholders (n = 1).

Study methods

Studies employed several different, and sometimes mixed, research methods.

Qualitative methods were most commonly used (93% of included studies used qualitative methods alone or in combination with other methods), and were predominantly structured as interviews or focus group discussions. Interviews were conducted with refugees/IDPs or other community-based actors and took the form of in-depth, semi-structured or biographical interviews. Focus group discussions were formal and informal, stratified by age and gender, or designed as workshops or anecdote circles. Researchers employed varied—and creative and participatory—methods within such interviews and focus group discussions to collect data and learn about the nuances of refugee/IDPs lives and experiences. These techniques included: storytelling, oral histories, and vignettes, safety, community, dream, and body mapping, free listing, timelining, ranking, sorting, and venn-diagramming, art making, document analysis, photo-elicitation, diaries and role play. Studies also used qualitative methods such as observations and methodologies such as ethnographies.

Studies also employed PhotoVoice (or derivatives of participant or auto-photography) and artistic co-creation. Through the taking of photos and their presentation and discussion, photo-based methods enable community strengths, issues, and concerns to be documented and can promote critical dialogue [ 55 ]. Types of artistic co-creation included song, written tests, deejay sets, ‘Grindr poetry’, video poetry, performance, drag, and graphic design [ 67 ].

Researchers also utilised quantitative or mixed-qualitative and quantitative methods for data collection. Three studies used quantitative methods alone, including a knowledge, attitudes and practices survey, a randomised household survey with ‘heads of households’ [ 79 ] and an attitude survey incorporating the ‘Gender Equitable Men’ scale [ 85 ]. Two of these quantitative studies described their participatory approach as involving the creation of advisory groups consisting of refugees who were involved in decision-making about the research [ 71 , 85 ], however the third mentioned using a ‘participatory approach’ and ‘participatory method’ without further explanation [ 79 ]. Further, in this third study, only sampling household heads is limiting as this often results in over-representation of men, limiting women’s participation as research participants. Mixed methods included prioritization exercises (with numerical rankings) and the use of the ‘Sensemaker’ method, which documents micro-narratives of refugees/IDPs lived experiences and, then from these narratives, using a signification framework, participants then create their own set of questions to analyze such narratives [ 78 ].

As will be discussed in later sections, some of these methods were explicitly framed as being participatory. These research methods are distinct from the broader participatory approaches employed.

Gender and GBV focus

In total, 68% of included studies (n = 32) focused on GBV. This included 14 studies that focused solely on GBV, and 18 studies which looked at GBV along with other themes specifically: GBV and adolescent girls (n = 4), GBV and LGBTQIA + (n = 4), GBV and sexual and reproductive health (n = 2), and various combinations of GBV with other topics including economic development, maternal and child health, economic development, division of labour/gender roles, decision-making/leadership and masculinities.

The remaining 32% of included studies (n = 15) focused on topics related to gender equality more broadly without discussing GBV. These topics included LGBTQIA + (n = 4), division of labour/gender roles (n = 2), sexual and reproductive health (n = 2), masculinities (n = 1), and various combinations of division of labour/gender roles with other topics (n = 6). The greater proportion of studies focused on GBV rather than gender equality more broadly may reflect the fact that researching GBV requires greater sensitivity and care (which participatory approaches and methods may help with). For included papers focusing on humanitarian settings (rather than high-income countries hosting refugees), the emphasis on gender equality may also reflect the greater focus within the humanitarian sector on GBV compared to other gender-related issues.

Definitions of participation and ‘participatory’ research

Across all included studies, no definition of the core concept of ‘participation’ was discussed, despite recognition that participation is important. Existing frameworks and definitions were not referenced in these studies.

However, included studies do describe or define different participatory approaches to research. For example, Lenette and colleagues [ 73 ] describe participatory research as research that ‘begins from a social, ethical and moral commitment not to treat people as objects of research but rather, to recognise and value the diverse experiences and knowledges of all those involved (…) Participatory research is often seen as a method that promotes cultural continuity and values gender-specific standpoints’ (757). Feminist participatory research is described by Thompson [ 92 ] as ‘a conscious break with research programs grounded in empiricism (…) Feminist participatory research, then, is not just neutral on the topic of women. It is instead openly committed to a diverse range of women's experiences and women's struggles. It is guided by feminist critiques of science and employs methods that preserve women's experiences in context’ (31).

The concept of ‘Participatory Action Research’ (PAR) was also described in several studies, with a focus on principles of PAR [ 50 , 51 , 52 , 60 , 65 ]. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) principles were also discussed in a few studies [ 64 , 68 , 69 ]. Other concepts that were described were PhotoVoice [ 74 ], action research [ 66 ] and ‘community participatory methodology’ [ 57 ].

Rationale for promoting refugee/IDP participation

Reviewed papers provided several rationales for promoting participation of refugees/IDPs in their research including: their identity as a refugee/IDP, their gender, and their position within power hierarchies. For example, various papers (n = 9) voiced that the experiences and qualities that are intrinsic to refugee/IDP status mandated their active participation in research. With a consensus that there is an overall lack of attention to this population [ 64 ], coupled with their rapidly increasing numbers [ 74 ], authors believed it was especially important to include those with “local, individual and marginalized viewpoints” [ 59 ] that are often outside of traditional “Western” research [ 68 , 69 ], in order to capture a holistic view of their lives [ 94 ]. Authors also viewed their participation as an empowering process, which could counter act often romanticized perceptions and representations of their lives, such as that they are all traumatized [ 95 ]. Participatory research was also positioned as responding to the fact that research with refugees does not use strengths-based approaches [ 55 ]. Thompson believed participation—via the recall and collection of their stories—could help participants to reconstruct their lives [ 92 ].

Further, several reviewed papers (n = 8) cited feminist theory as a rationale for promoting participation amongst research with refugees/IDPs [ 28 , 55 , 67 , 70 , 74 , 77 , 92 , 94 ]. Most referred to encouraging women and girls to join the research process. However, one paper purposely included adolescent boys so to understand their perspectives on issues around gender inequality and marriage [ 78 ] and a few purposely included LGBTQIA + refugees/IDPs (n = 2). Overall, rationales for including women and girls were two-fold. First, they either conceptualized knowledge as a (feminist) process of emancipation and social change [ 95 ], and thus, included women and girls to address gender stereotypes that persist in research [ 74 ]. For example, they recognized that women and girls are less likely to participate in mixed-gendered research spaces and that their contributions to knowledge are often viewed as less valuable [ 95 ]. Secondly, the rationale used for including women and girls was in order to ensure that research recommendations would be centred on their specific needs and experiences, for example, to ensure that their specific safety concerns would be included.

Moreover, many studies (n = 10) sought to include refugees/IDPs within the research process to address the power imbalances that are often present within research and ensure more democratic equitable research. This often included descriptions of how power dynamics can make research ‘exploitative’ [ 95 ]. In Pangcoga and Gambir’s study, the Sensemaker method made the research more ‘democratic’, enabling participants voices to be centred while addressing power imbalances [ 78 ], while others identified how their choice of methods such as participatory photography, visual methods and production of artistic outputs helped to reduce power dynamics [ 28 , 67 , 94 ]. In both ‘Empowered Aid’ studies, PAR was stated as a means of recognising and tackling power imbalances [ 50 , 51 ]. Other studies also took a holistic approach to being participatory through strategies such as asking open-ended questions [ 28 , 73 ], reflecting on power and positionality [ 28 , 92 , 94 ], spending more time with refugees and thinking about how best to represent their lives [ 28 , 72 , 94 ]. Studies acknowledged that it was challenging to fully address power imbalances [ 95 ].

Level of focus on participation

As part of the extraction process, we classified included studies according to how authors’ described their study’s focus on on participation. This was driven by our recognition—also discussed in literature—that the concept of participation has often been co-opted by authors [ 6 ] when describing their methods, without due consideration to the fidelity and robustness of participation. Firstly, we classified 15% of studies (n = 7) as having ‘low’ content on participation—describing studies where being participatory was mentioned in passing only, without further explanation. We then used the framing by Lenette et al. [ 1 ] to contrast the use of a participatory ‘approach’ (i.e. a holistic process made up of multiple strategies to embed participation across the research process), and the use of a participatory ‘method’ (i.e. the use of a specific research method such as PhotoVoice or video). We created three categories to classify the studies that were not categorised as ‘low’: studies that only use participatory method(s), studies that only use a participatory approach, or studies that use both a participatory method and participatory approach. We suggest that simply using a participatory method is not always sufficient to address power hierarchies within research, rather using a more holistic participatory approach encompassing multiple strategies is more helpful.

Content classified as ‘low’ (n=7) tended to involve singular references to participation or being participatory without any further explanation [ 61 , 79 , 80 , 81 , 86 , 96 , 97 ]. For example, using the term ‘participatory qualitative design’ only in the abstract with no additional reference in the text [ 61 ], or referring to a ‘participatory approach’ or ‘participatory research’ without further explanation [ 79 , 86 , 97 ].

One study classified as low referred to ‘ethnographic participatory fieldwork’ [ 81 ] and listed classroom interactions and language portraits as examples, without explaining these methods further. It is unclear if the methods alone were the reason for using the term ‘participatory’ or if something related to the methodology of the ethnographic fieldwork was participatory. Similarly, another study mentioned ‘participatory FGDs’ and said this involved drawing and poetry, but did not provide further detail on this approach [ 96 ], seeming to reflect Ozkul’s [ 7 ] critique that arts-based methods are sometimes automatically assumed to be participatory.

Some of these examples may reflect what Cornwall and Brock [ 98 ] refer to as ‘buzzwords’. Using the term participation or participatory may invoke positive associations without resulting in refugees or IDPs meaningfully participating in research processes. However, we also recognise that the level of content included to describe participatory approaches and methods are not always reflective of whether studies actually used these approaches. For example, disciplinary styles of writing, journal requirements and feedback from peer reviewers may all result in less (or more) description being added about methods.

Studies that only use participatory approaches

In total, 17 studies used a holistic participatory approach in isolation—without also mentioning use of a participatory method. The table below outlines the types of strategies used to enhance participation. We took a broad approach in categorising these studies as taking a participatory approach, recognising that not all practices were explicitly labelled as participatory. For example, one study [ 72 ] only mentioned the word ‘participatory’ in passing, yet the practices described in the methods (including having an advisory committee that was connected to the community) align with participatory approaches.

In a few cases, it was not clear if studies also used a participatory method. For example, two studies included community members at each stage of the research as part of the broader participatory approach, but it was unclear if the use of video-elicitation within the FGDs constituted a participatory method [ 68 , 69 ]. In another case where a feminist participatory approach was described, it was not clear if the use of ‘dream narratives’ may constitute use of a participatory method [ 92 ].

Studies that only use participatory methods

In total, 11 studies used participatory methods in isolation [ 53 , 54 , 55 , 59 , 62 , 63 , 74 , 83 , 84 , 87 , 89 ]. The methods chosen included participatory photography including participatory mapping [ 84 , 89 ], PhotoVoice [ 62 ] and participatory ranking methodologies [ 53 ]. A few studies did not fully explain their use of participatory methods. One study mentioned the use of ‘participatory workshop methods’ multiple times without explaining what this meant [ 83 ]. One study used PAR meetings with refugees to gather data [ 54 ] and another used ‘participatory learning and action’ (PLA) [ 59 ], but neither outlined in detail the PAR and PLA approaches, though Akash & Chalmiers noted that they describe their methodology in another paper [ 54 ].

In a few cases, studies were stated as using a participatory approach, however in reality these described methods and were counted within the ten studies above that only talked about methods. In two studies, CBPR was stated as the methodology but only PhotoVoice [ 55 ] or only PhotoVoice and interviews [ 74 ] were used as the method—and there was no other indication that a broader CBPR approach was taken. Elsewhere PAR was stated as the methodology, but in one study only the use of photo-ethnography as method rather than PAR more broadly was evident based on the paper description [ 87 ]. Another study mentioned the use of PAR meetings which were also described as creating space for women ‘to enable women to flexibly tell their own stories of marriage using a life events-narrative approach’ [ 54 ]—which sounds less like a participatory method and more like a life history interview.

Studies that use both participatory methods and participatory approaches

In total, 11 studies clearly stated the use of both a participatory approach as well as a participatory method [ 28 , 50 , 51 , 56 , 58 , 67 , 73 , 78 , 82 , 91 , 94 ].

Strategies used to enhance participation

The most common strategy used within the 27 studies that took a participatory approach was involving participants in design, data collection and analysis (including through an advisory group), which 17 studies mentioned. Other strategies included refugees/IDPs only participating in design/influencing the research agenda (n = 5), refugees/IDPs only participating in analysis/feedback (n = 3), using peer data collectors (n = 4) and providing in-kind or financial compensation for refugees/IDPs who participated (n = 3) (Table 4 ).

While this list (which is not mutually-exclusive) represents a helpful indication of the ways in which GBV and gender equality research has sought to promote refugee/IDP participation, it is important to note the challenges in using these strategies which many studies discussed. The time and financial cost associated with participatory approaches can be significant; and it is not always possible to compensate refugees/IDPs for their time [ 66 ]. Even if researchers intend to promote participation, refugees/IDPs may not always be accustomed to or comfortable with participating and may not engage as much as hoped [ 95 ]. Efforts to enable participants to co-create outputs may not always be successful as participants may be not used to having more autonomy and voice [ 67 ]. These challenges complicate efforts to promote refugee/IDP participation.

Impacts of participation of refugees/IDPs in research

Some studies explicitly commented on the impacts of using participatory methods and strategies. For example, studies stated that using this approach to research increased participants’ well-being and confidence [ 55 , 94 ]. Participants reported feeling heard [ 64 ]. Participatory research also created opportunities for socialisation amongst participants [ 73 ]. Engaging communities throughout the research enabled communities to create knowledge and develop local strategies for change [ 66 ].

Other studies did not specifically comment on concrete impacts but discussed the potential of participatory methods and strategies to contribute towards increasing solidarity [ 95 ], creating transformative experiences for participants [ 74 ], preventing research fatigue [ 95 ], and improving research rigour and ethics [ 69 ].

This scoping review explored how the concept of participation is operationalised in research with refugees and IDPs. Our review highlights how despite recognition that participation of refugees/IDPs is important for research, the concept of participation continues to be used tokenistically, as a ‘buzzword’ [ 98 ] that is misappropriated to describe a myriad of research approaches and methods.

In our study, we found that while many studies use gender (including specifically drawing on feminist theory), or refugee/IDP status to explain the reason for taking a participatory approach, in many cases there was not a concerted effort to understand and outline the reasons why participation is important—and even less effort to document the impacts of using participatory approaches and methods. The power hierarchies within research more generally do provide a strong incentive for researchers to tackle imbalances inherent within the research process, however these dynamics were not often discussed in included papers. We suggest that conducting power analysis more broadly—including analysing power dynamics within research, gendered power dynamics and dynamics between refugess/IDPs and researchers—may provide stronger rationale for promoting participation, making it easier to identify concrete opportunities for refugee/IDP participation in research.

While only a small number of studies were classified as having limited/passing references to being participatory, those that did include references to either using participatory methods or participatory approaches more broadly, at times did not fully explain what exactly was participatory about the research. Methods like FGDs were described as being participatory, without it being clear what made this approach participatory. Even when approaches like CBPR or PAR were referenced, the descriptions of research practices were sometimes limited. Some of this gap is due to journal and peer reviewer expectations, as well as practices within research disciplines—rather than necessarily reflecting that participatory methods and approaches are not being used. Thus, we recommend more robust descriptions of how researchers action participation within research outputs, so that the wider research community can learn not only what they have accomplished, but how they accomplished it.

Where participatory approaches were used, we found that the use of specific strategies to promote participation tended to focus on involving refugees/IDPs in providing advice across the research process—a positive sign. In some cases, refugees were engaged as ‘peer researchers,’ though this strategy has also been critiqued by others as containing potential for exploitation [ 26 , 99 ]. Importantly, engaging refugees/IDPs during analysis was less common, representing a gap in current strategies to promote participation, which others have also identified [ 100 ]. Thus, we suggest aiming to involve refugees and IDPs more in analysis, all whilst recognising also the additional burden on this engagement might place on refugees by seeking to find less time-intensive ways of seeking input on the findings and ensuring renumeration for this participation. Moreover, providing some kind of incentive or benefit for refugees/IDPs to participate was only mentioned in a few studies, although this would have meaningful impact for refugees/IDPs. While this review highlights that among refugees and IDPs there are limited examples of the systematic use of both participatory approaches across a research process, and use of participatory methods, we suggest much can be learnt from feminist participatory research among other populations. Feminist participatory research continues to provide innovative ways of understanding power, challenging how knowledge is produced (and by whom) and framing issues from women’s perspective [ 33 , 36 , 43 ]. However, many of these methodological advancements are yet to be tested in settings with refugees and IDPs. We suggest that particularly in humanitarian emergencies, the default assumption may be that using innovative methods is less realistic. Indeed, the urgent nature of the humanitarian response has at times acted as a justification for not considering issues of power in sufficient depth or not spending enough time to understand issues before responding [ 28 , 101 ]. In the same way, the limited level of innovation within research methods among refugees and IDPs may be driven by assumptions about what is possible to implement within a humanitarian emergency. Notwithstanding the challenges in obtaining research funding for research in humanitarian settings that uses innovative methods, we suggest more work needs to be done to consider the value of participatory methods—beyond PhotoVoice—for research among refugees and IDPs.

We recommend that future research among refugees and IDPs should:

More explicitly detail how researchers sought to promote participation of refugees/IDPs, including clearer conceptualisations of what constitutes refugee/IDP participation and how they operationalised this.

Consider the use of innovative, feminist research methods that can challenge power dynamics and provide new opportunities for refugees and IDPs to share their lived experience. Learning from feminist participatory research methods used outside of refugee and IDP populations may provide important lessons to bring innovative research methods into the humanitarian sector.

Continue to engage refugees and IDPs in research design and analysis in particular, and use other strategies such as in-kind and financial compensation to recognise the contribution refugees and IDPs make towards research.

Include more explicit reflection on how power affects the research process and deliberately incorporate participatory approaches and methods to address this, including drawing on feminist and participation frameworks applied in other settings to ensure refugee/IDP participation is meaningful and not solely lip service. This should include consideration of how participatory approaches and methods align with key principles of rigorous, ethical research.

Seek to analyse the impacts of incorporating participatory approaches and methods on refugees/IDPs themselves, to help with documenting both positive impacts and unintended/negative impacts.

Availability of data and materials

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

Change history

03 january 2024.

A Correction to this paper has been published: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13031-023-00559-0

Lenette C, Stavropoulou N, Nunn CA, Kong ST, Cook T, Coddington K, Banks S. Brushed under the carpet: examining the complexities of participatory research. Res All. 2019;3:161–79.

Article Google Scholar

Humanitarian Accountability Partnership. 2013 Humanitarian Accountability Report. 2013.

Filler T, Benipal PK, Torabi N, Minhas RS. A chair at the table: a scoping review of the participation of refugees in community-based participatory research in healthcare. Global Health. 2021;17:1–11.

Google Scholar

Kia-Keating M, Juang LP. Participatory science as a decolonizing methodology: leveraging collective knowledge from partnerships with refugee and immigrant communities. Cult Divers Ethn Minor Psychol. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1037/cdp0000514 .

Martin SB, Burbach JH, Benitez LL, Ramiz I. Participatory action research and co-researching as a tool for situating youth knowledge at the centre of research. London Rev Educ. 2019;17:297–313.

Starodub A. Horizontal participatory action research: Refugee solidarity in the border zone. Area. 2019;51:166-17S3.

Ozkul D. Participatory research: still a one-sided research agenda? Migr Lett. 2020;17:229–37.

Chambers R. Whose reality counts? Putting the first last. Practical Action Publishing Ltd, London. 1997.

Cornwall A. Whose voices? Whose choices? Reflections on gender and participatory development. World Dev. 2003;31:1325–42.

Cooke B, Kothari U. Participation: the new tyranny? New York: Zed; 2001.

Eyben R. Uncovering the politics of “evidence” and “results”. A framing paper for development practitioners. 2013.

Olivius E. (Un)governable subjects: the limits of refugee participation in the promotion of gender equality in humanitarian aid. J Refug Stud. 2014;27:42–61.

Brown D, Donini A, Knox Clarke P. Engagement of crisis-affected people in humanitarian action. 2014.

Anderson MB, Brown D, Jean I. Time to listen. Hearing people on the receiving end of international aid, 1st ed. CDA Collaborative Learning Projects, Cambridge, MA. 2012.

Women’s Refugee Commission. Understanding past experiences to strengthen feminist responses to crises and forced displacement. New York. 2021.

Vaughn LM, Jacquez F. Participatory research methods—choice points in the research process. J Particip Res Methods. 2020. https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.13244

Fine M, Torre ME, Oswald AG, Avory S. Critical participatory action research: methods and praxis for intersectional knowledge production. J Couns Psychol. 2021;68:344–56.

Article PubMed Google Scholar

Rodriguez Espinosa P, Verney SP. The underutilization of community-based participatory research in psychology: a systematic review. Am J Community Psychol. 2021;67:312–26.

Wallerstein N, Oetzel JG, Sanchez-Youngman S, et al. Engage for equity: a long-term study of community-based participatory research and community-engaged research practices and outcomes. Heal Educ Behav. 2020;47:380–90.

McFarlane SJ, Occa A, Peng W, Awonuga O, Morgan SE. Community-based participatory research (CBPR) to enhance participation of racial/ethnic minorities in clinical trials: a 10-year systematic review. Health Commun. 2022;37:1075–92.

Patel MR, TerHaar L, Alattar Z, Rubyan M, Tariq M, Worthington K, Pettway J, Tatko J, Lichtenstein R. Use of storytelling to increase navigation capacity around the affordable care act in communities of color. Prog Commun Heal Partnerships Res Educ Action. 2018;12:307–19.

Sharpe L, Coates J, Mason C. Participatory research with young people with special educational needs and disabilities: a reflective account. Qual Res Sport Exerc Heal. 2022;14:460–73.

Lenette C, Brough M, Schweitzer RD, Correa-Velez I, Murray K, Vromans L. ‘Better than a pill’: digital storytelling as a narrative process for refugee women. Media Pract Educ. 2019;20:67–86.

Duran B, Oetzel J, Magarati M, et al. Toward health equity: a national study of promising practices in community-based participatory research. Prog Community Heal Partnerships Res Educ Action. 2019;13:337–52.

Bottomley B. NGO strategies for sex and gender-based violence protection and accountability in long-term displacement settings: Reviewing women’s participation in humanitarian programmes in Dadaab refugee complex. RLI Work Pap No. 2021;56:1–20.

Pincock K, Bakunzi W. Power, participation, and ‘peer researchers’: addressing gaps in refugee research ethics guidance. J Refug Stud. 2021;34:2333–48.

Anderson K. Tearing down the walls. Confronting the barriers to internally displaced women and girls’ participation in humanitarian settings. 2019.

Lokot M. The space between us: feminist values and humanitarian power dynamics in research with refugees. Gend Dev. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552074.2019.1664046 .

Omata N. Unwelcome participation, undesirable agency? Paradoxes of de-politicisation in a refugee camp. Refug Surv Q. 2017;36:108–31.

Doná G. The microphysics of participation in refugee research. J Refug Stud. 2007;20:210–29.

Rass E, Lokot M, Brown FL, Fuhr DC, Asmar MK, Smith J, McKee M, Orm IB, Yeretzian JS, Roberts B. Participation by conflict-affected and forcibly displaced communities in humanitarian healthcare responses: a systematic review. J Migr Heal. 2020;1–2: 100026.

Mayra K. Birth mapping: a visual arts-based participatory research method embedded in feminist epistemology. Int J Qual Methods. 2022;21:160940692211053.

Fileborn B. Digital mapping as feminist method: critical reflections. Qual Res. 2023;23:343–61.

Cin FM, Süleymanoğlu-Kürüm R. Participatory video as a tool for cultivating political and feminist capabilities of women in Turkey. In: Particip Res Capab Epistemic Justice. Springer International Publishing, Cham; 2020, pp 165–188.

Lykes MB, Bianco ME, Távara G. Contributions and limitations of diverse qualitative methods to feminist participatory and action research with women in the wake of gross violations of human rights. Methods Psychol. 2021;4: 100043.

Buchanan K, Geraghty S, Whitehead L, Newnham E. Woman-centred ethics: a feminist participatory action research. Midwifery. 2023;117: 103577.

Crupi K, Godden NJ. Feminist evaluation using feminist participatory action research: guiding principles and practices. Am J Eval. 2023. https://doi.org/10.1177/10982140221148433 .

Mcdiarmid T, Pineda A, Scothern A. We are women! We are ready! Amplifying women’s voices through feminist participatory action research. Eval J Australas. 2021;21:85–100.

Jumarali SN, Nnawulezi N, Royson S, Lippy C, Rivera AN, Toopet T. Participatory research engagement of vulnerable populations: employing survivor-centered, trauma-informed approaches. J Particip Res Methods. 2021. https://doi.org/10.35844/001c.24414

Anderson KM, Karris MY, DeSoto AF, Carr SG, Stockman JK. Engagement of sexual violence survivors in research: trauma-informed research in the THRIVE study. Violence Against Women. 2023;29:2239–65.

Leung L, Miedema S, Warner X, Homan S, Fulu E. Making feminism count: integrating feminist research principles in large-scale quantitative research on violence against women and girls. Gend Dev. 2019;27:427–47.

Dorries H, Harjo L. Beyond safety: refusing colonial violence through indigenous feminist planning. J Plan Educ Res. 2020;40:210–9.

Guy B, Arthur B. Feminism and participatory research: exploring intersectionality, relationships, and voice in participatory research from a feminist perspective. SAGE Handb. Particip. Res. Inq. 2021.

Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:467–73.

Munn Z, Peters M, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18:1–7.

Chang S. Scoping reviews and systematic reviews: Is it an either/or question? Ann Intern Med. 2018;169:502–3.

Piasecki J, Waligora M, Dranseika V. Google search as an additional source in systematic reviews. Sci Eng Ethics. 2017. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11948-017-0010-4 .

Article PubMed PubMed Central Google Scholar

Adams RJ, Smart P, Huff AS. Shades of grey: guidelines for working with the grey literature in systematic reviews for management and organizational studies. Int J Manag Rev. 2017;19:432–54.

UN Women Concepts and definitions. https://www.un.org/womenwatch/osagi/conceptsandefinitions.htm . Accessed 4 Apr 2023.

Potts A, Fattal L, Hedge E, Hallak F, Reese A. Empowered Aid: Transforming gender and power dynamics in the delivery of humanitarian aid. Participatory action research with refugee women & girls to better prevent sexual exploitation & abuse—Lebanon Results Report. 2020.

Potts A, Kolli H, Hedge E, Ullman C. Empowered aid: transforming gender and power dynamics in the delivery of humanitarian aid. Participatory action research with refugee women & girls to better prevent sexual exploitation & abuse—Uganda Results Report. 2020.

Affleck W, Thamotharampillai U, Jeyakumar J, Whitley R. “If One Does Not Fulfil His Duties, He Must Not Be a Man”: masculinity, mental health and resilience amongst Sri Lankan Tamil refugee men in Canada. Cult Med Psychiatry. 2018;42:840–61.

Ager A, Bancroft C, Berger E, Stark L. Local constructions of gender-based violence amongst IDPs in northern Uganda: analysis of archival data collected using a gender- and age-segmented participatory ranking methodology. Confl Health. 2018;12:10.

Al Akash R, Chalmiers MA. Early marriage among Syrian refugees in Jordan: exploring contested meanings through ethnography. Sex Reprod Heal Matters. 2021;29:287–302.

Dantas J, Lumbus A, Gower S. Empowerment and health promotion of refugee women: the photovoice project. 2018.

Edström J, Dolan C. Breaking the spell of silence: collective healing as activism amongst Refugee male survivors of sexual violence in Uganda. J Refug Stud. 2019;32:175–96.

Ellis BH, MacDonald HZ, Klunk-Gillis J, Lincoln A, Strunin L, Cabral HJ. Discrimination and mental health among Somali refugee adolescents: the role of acculturation and gender. Am J Orthopsychiatry. 2010;80:564–75.